Mitochondrial Replacement

Recent News

On the 3 February 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report, Mitochondrial replacement techniques: Ethical, social, and policy considerations. With this report, written at the request of the Food and Drug Administration, the United States is poised to proceed with research involving mitochondrial replacement. Authored by the Committee on the Ethical and Social Policy Considerations of Novel Techniques for Prevention of Maternal Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA Diseases, it makes a number of important contributions to the ethics and policy debates. In sum, the Committe concluded that "it is ethically permissible to conduct clinical investigations of MRT [Mitochondrial replacement techniques]. To ensure that clinical investigations of MRT were performed ethically, however, certain conditions and principles would need to govern the conduct of clinical investigations and potential future implementation of MRT." Françoise Baylis was an external reviewer and provided comments on an earlier draft of the report. Several NTE members' work was referenced in the final published version. Read more here.

Overview

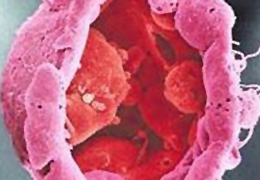

For the past few years there has been considerable debate about the ethics of germ-line genetic interventions, with scientists in different countries arguing for the clinical use of mitochondrial replacement technology to avoid the birth of children with mitochondrial disease.

Diseases resulting from mutations in mitochondrial DNA can include poor growth, deafness, blindness, heart disease, liver disease, kidney disease, learning disabilities, loss of muscle coordination, muscle weakness, and neurological problems. Preclinical research suggests it may be possible to avoid these diseases by replacing disease-linked mitochondrial DNA with healthy mitochondrial DNA from another woman’s egg. With the use of this technology, women with diseased mitochondrial DNA could have genetically-related children free of mitochondrial disease. Use of this technology, however, involves crossing the boundary of germline genetic manipulation. In Canada this is prohibited by section 5(f) of the Assisted Human Reproduction Act.

While mitochondrial manipulation has not been the subject of much discussion in Canada, there has been considerable debate about this in both the United States and the United Kingdom.

United States

In February 2014, the Cellular, Tissue and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA Briefing Document [182 - KB]) met to discuss human egg modification to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial disease (transcript of meeting [PDF - 334 KB]). Françoise Baylis sent a written submission [PDF - 88 KB] concluding that the various ethical objections to the science were serious cause for concern. Many speakers at the advisory committee meeting urged caution, noting that egg modification could "alter the human species" and "open the door to genetically-modified children." The FDA "heard the concerns expressed at the advisory committee meeting,” and determined that "there probably aren't enough data in animals or in vitro to conclusively move on to human trials without answering a few additional questions." On January 27, 2015 the Institute of Medicine appointed a committee to study the "Ethical and Social Policy Considerations of Novel Techniques for Prevention of Maternal Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA Diseases." A final report of this project was released 3 Feburary 2016.

United Kingdom

In 2013, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (the UK’s regulator overseeing the use of gametes and embryos in fertility treatment and research) endorsed mitochondrial replacement [PDF - 390 KB] as a technique to avoid serious mitochondrial diseases. Although it recognized “strong ethical concerns that some respondents to the consultation expressed,” the HFEA concluded that there was “general support for permitting mitochondria replacement in the UK, so long as it is safe enough to offer in a treatment setting and is done so within a regulatory framework.”

This conclusion marked a significant departure from past practice, and some have suggested the HFEA’s findings were not reflective of adequate public consultation. On February 27, 2014, the UK government announced a new consultation [PDF - 167 KB] on its draft regulations regarding mitochondrial replacement, in which it called for “any new evidence since the 2013 update.” On March 21, 2014, the Center for Genetics and Society wrote a letter (co-signed by Françoise Baylis) [PDF - 312 KB] in response to the new call for evidence. This letter urged the HFEA to “carefully examine and thoroughly review and follow up on the wide range of safety and efficacy concerns raised by the FDA committee” on mitochondrial replacement, and to provide “an accurate summary of the current state of expert and scientific understanding.” Previously, Françoise Baylis co-signed a letter to the Times regarding the scope of the consultation [PDF - 408 KB], which warned that for the UK to undertake the change “without consulting its international partners would create a very serious precedent.”

On February 3, 2015 members of the UK House of Commons approved the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Mitochondrial Donation) Regulations. These regulations were to allow "mitochondrial donation techniques to be used under licence as part of IVF treatment with the aim of preventing the transmission of serious mitochondrial disease from mother to child." The House Lords approved the regulations on February 24, 2015 which came into force on October 29, 2015. The HFEA is now developing a licensing framework "through which applications can be considered from clinicians wanting to offer the two techniques set out in the regulations". For more information on the licensable techniques, visit the mitochondrial pages of the HFEA website.

Last updated August 2017.