Canada is experiencing its largest measles outbreak in more than a decade, with cases rising to about 500 in recent weeks. The majority are in Ontario and Quebec, but other provinces are seeing cases of the highly contagious viral infection as well. Health officials have reported that many of the cases are among people who were not immunized.

The illness, once thought to be eradicated in Canada since 1998 aside from the occasional travel-related case, is making a comeback amid dropping measles vaccination rates across the country. The measles, mumps and rubella vaccine comes in two doses and the Public Health Agency of Canada estimates that coverage for the first dose decreased to around 83 per cent in 2023 from about 90 per cent in 2019. It fell to around 76 per cent from about 86 per cent over the same period for the second dose.

We asked Dr. Jeannette Comeau, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Dalhousie, about measles, why we are seeing such a sharp spike in cases and who should be vaccinated.

What is measles and how is it spread?

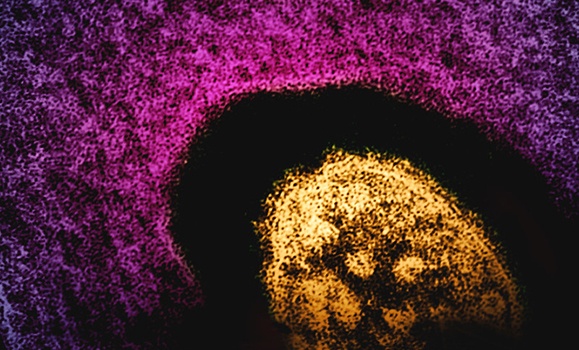

Measles, or rubeola, is an infection caused by Morbillivirus, a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA virus within the Paramyxoviridae family. It is considered one of the most contagious pathogens; 90 per cent of susceptible exposed individuals will contract the disease.

Measles is spread primarily through airborne dissemination of respiratory droplets through coughing or sneezing by an infectious individual. These droplets, due to their tiny size, can stay in the air for extended periods of time (hours), even after the infected individual has left the room. The incubation period (period of time from exposure to onset of first symptoms) is seven days post first exposure to 21 days post last exposure. The time during which someone can transmit infection is four days before until four days after the first day of appearance of the rash.

What are the symptoms?

The classic presentation of measles begins with a fever and the "3 C's" (cough, coryza, conjunctivitis). The enanthem — Koplik spots — usually appears two to four days into the illness, followed by the exanthem, a maculopapular rash four to six days into the illness. The rash usually begins on the head and spreads to cover the whole body within three days. Most individuals will have a peak of fever six to nine days into the illness followed by recovery.

Pneumonia can occur in up to one in 20 infected individuals

Complications can include pneumonia, encephalitis and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a degenerative central nervous system disease presenting up to 11 years after infection in four to 11 per 100,000 infected individuals. Pneumonia can occur in up to one in 20 infected individuals, while encephalitis occurs in one in 1,000. Death, usually from respiratory complications, occurs in 1 in 1,000 infected individuals.

When infected, infants under five years, pregnant people and immunocompromised individuals are at higher risk of severe disease and complications.

Why are we seeing outbreaks in the United States and Canada, where it had been considered eliminated in 2000 and 1998 respectively?

Elimination meant we weren't seeing sustained transmission within the United States and Canada anymore. The resurgence of measles, despite elimination status, is primarily due to a decline in herd immunity because of declining vaccination rates. This decline can be attributed to:

- Vaccine hesitancy: Misinformation campaigns and anti-vaccination sentiment have eroded public trust in vaccine safety and efficacy, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importation: Increased international travel facilitates the importation of measles virus from endemic regions, leading to outbreaks in susceptible communities.

- Health care access disparities: Limited access to health care and vaccination services in marginalized or remote/rural communities can lead to pockets of susceptibility

Who is vulnerable now and who should get vaccinated?

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, it was estimated that almost all individuals would have had the infection prior to 18 years of age. The vaccine was introduced in the 1960s in Canada and recommended as a one-dose schedule in 1983. In 1996-1997, the two-dose schedule was introduced and measles was declared eliminated in 1998. Two doses are considered to confer protection for life.

Measles immunization, administered as either MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) or MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella, varicella) vaccine, is currently recommended for infants at 12 and 18 months of age. An early dose of vaccine can be given to babies as young as six months of age if there is anticipated exposure (i.e. travel to an endemic area), however the child will still require two additional doses after 12 months of age to ensure lifelong immunity.

The decline in vaccine uptake poses a significant public health challenge, potentially leading to the re-emergence of other vaccine-preventable diseases.

In a setting of high vaccine uptake, this means that infants under 12 months of age and immunocompromised individuals are most vulnerable to infection. Babies under three months may have some protection due to antibody transfer during the final trimester of pregnancy, but this passive immune protection wanes.

In addition to routine immunization, it is recommended that individuals born after 1970 who are unimmunized or have only received one dose of a measles-containing vaccine book an appointment to be immunized, unless they are pregnant or immunocompromised in which case they should speak to their care provider. Individuals born before 1970 may consider getting one dose of vaccine if the risk of exposure is high (i.e. travel to an endemic area).

What has happened to vaccine uptake in recent years and if it has dropped, could we see the resurgence of other viruses?

The decline in vaccine uptake poses a significant public health challenge, potentially leading to the re-emergence of other vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccine uptake rates below critical vaccination thresholds, and the impact of reduced herd immunity leads to increased individual susceptibility and the potential for widespread outbreaks. This trend raises concerns about the resurgence of other vaccine-preventable diseases, including pertussis, diphtheria and polio. We have seen pertussis outbreaks in North America periodically, however diphtheria and polio cases remain rare.

A systems-level approach, encompassing robust surveillance, evidence-based communication strategies and targeted interventions to address vaccine hesitancy, is imperative to mitigate this risk.