Author Brittany Kraus is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Dalhousie University

“How to exist and not to belong?” asks the unnamed protagonist and narrator of Rawi Hage’s second novel, Cockroach.

The 2008 novel by Hage, an acclaimed Lebanese Canadian writer and photographer based in Montréal, Québec, explores issues of immigration, assimilation, belonging and identity in the early post-9/11 world. The story unfolds through the eyes of an impoverished and psychologically disturbed Arab migrant in Montréal.

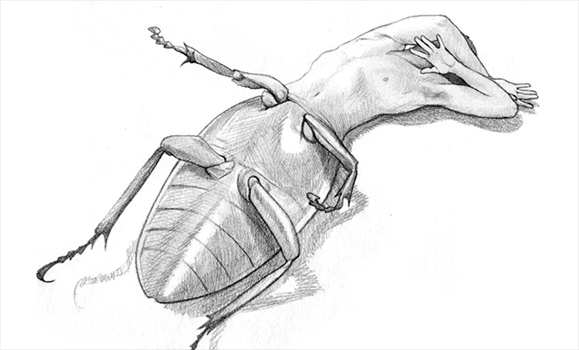

The unnamed protagonist becomes increasingly convinced he is half human, half insect, as he struggles to cope with the traumatic realities of his life in Canada — and the violent memories of his war-torn past in an unidentified Middle Eastern country.

Cockroach generated significant discussion in Canada after winning an award from the Quebec Writers’ Federation and being shortlisted for other book prizes, and profiled on CBC’s Canada Reads 2014.

For some readers, the central conceit of Hage’s Cockroach immediately invites comparison to Kafka’s modern classic The Metamorphosis, in which a man named Gregor Samsa is suddenly (and inexplicably) transformed into a bug.

Whereas Samsa famously wakes up to discover he has been physically transformed into a giant bug, the insect evolution of Hage’s narrator-protagonist occurs as a slower, more deteriorative process. The transformation is entwined with the narrator’s material and moral circumstances.

Surreal and mundane

Hage’s most recently published debut short story collection, Stray Dogs: And Other Stories (2022), was shortlisted for Canada’s prestigious Scotiabank Giller Prize. His earlier novels include De Niro’s Game (2006), Carnival (2012) and Beirut Hellfire Society (2018).

The author’s lyrical and philosophical style, penchant for the absurd and unflinching exploration of disruptions engendered by war, capitalism, globalization and neoliberalism has earned him a prominent place in the literary world, with works translated into 30 languages.

Hage’s writing frequently blends the surreal with the mundane to examine the effects of violence and displacement on people and their identities. His fiction often revolves around the lives of socially and economically marginalized or “subaltern” figures, as explored by literary critic Gayatri Spivak, forced to make difficult decisions to survive the dehumanizing conditions of war, poverty, violence and subordination.

Question of belonging

Like Kafka, Hage is a writer of the abject, the exiled and the outsider. Multiple readers and scholars have also observed the blend of eastern and western literary influences in Hage’s work, from Homer to Dostoevsky to Arabic poetry and myth.

Hage lived through nine years of the Lebanese civil war during the 1970s and 1980s before immigrating to Canada in 1992.

When he accepted the prestigious IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for his debut novel De Niro’s Game, which is set against the backdrop of the Lebanese Civil War, Hage spoke about the formation of his literary identity:

“Born as a Christian Arab, a group whose existence is an integral part of a great Arabic and Islamic civilization, I grew up learning two languages and different histories, and at the age of 18 learned the English language and imbibed the canon of its great poets and writers. Later, as a traveler, a citizen, a worker, a reader, and a writer, I was, fortunately, bound to become a global citizen.”

In a 2011 interview with literature scholar Rita Sakr, Hage characterized his writing as “influenced by the crisis of identity and the conflictual nature of the question of belonging.”

Metamorphosis borne from necessity

In Hage’s Cockroach, as Canadian literatures scholar Kit Dobson observes, the narrator’s “Kafkaesque morphing into a cockroach occurs whenever he begins to contemplate any questionable act”; his metamorphosis is borne from necessity.

These “questionable acts,” whether sexual, social, moral or economic, are motivated by the narrator’s conflicting desire for belonging and escape from the normative bounds of law and society, as well as his unmet needs for survival:

“My welfare cheque was ten days away. I was out of dope. My kitchen had only rice and leftovers and crawling insects that would outlive me on Doomsday.”

In his cockroach form, he is able to enact the strategies necessary for his survival, while also appearing to embody and act out the fears and fantasies of the popular Western imagination of the immigrant “other.”

Systems, conditions that degrade existence

Cockroach’s protagonist is not, however, an easily sympathetic character. He engages in a variety of illegal and illicit acts, including theft, sexual voyeurism and worse. The protagonist’s behaviour towards women also invokes a harmful stereotype of male chauvinism and danger often associated with Middle Eastern men in orientalist and post-9/11 western media and cultural representation.

In the protagonist’s relationship with his court-mandated therapist, a white Québécois woman who represents the state in literal and figurative ways, he behaves in chauvinistic and, indeed, criminal ways — at one point, breaking into her home.

Through the protagonist’s relationship with her, the novel is at its problematic and brilliant best. The story challenges dominant narratives of hospitable Canadian multiculturalism while interrogating unequal power relations and the forces of globalization that create divisions of “us” and “them.”

Like the man-bug of The Metamorphosis, the insect of Cockroach becomes an allegory for the narrator’s alienation, a manifestation of his desire for mobility and freedom.

‘Atmosphere of oppression’

Despite what some readers see as parallels between The Metamorphosis and Cockroach, in an early interview with journalist Ben East, based in the United Kingdom, about Cockroach, Hage said “[Kafka’s] not an influence at all.” Hage pointed out “Kafka doesn’t and can’t have a monopoly on acts of metamorphosis” but said, “I suppose there is the same atmosphere of oppression — that’s probably more Kafka-like than the specifics of someone turning into an insect.”

Indeed, the book can be read through an existentialist literary tradition concerned with oppression and alienation that includes antecedents such as Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, Albert Camus’s The Stranger, Dostoyevsky’s Notes from The Underground, and Kafka.

At the same time, Hage’s point about Kafka not owning metamorphosis is also in keeping with the provocative, post-colonial spirit of his novel and its thieving protagonist. Acts of metamorphosis not only surely exceed Kafka through both the western literary canon, but also through post-colonial literary theory that examines hybridity and cultural translation.

Through the underground

Cockroach reminds us of the injustices and fractures people face due to systems designed to perpetuate displacement, unequal access and widening global divisions of labour and wealth.

But it is also a reminder of the limitations of sympathy as a measure of need, the fundamental rights of those who don’t readily inspire a dominant society’s compassion and the radical choices many people face in a struggle for survival and belonging.

As Hage writes: “Other humans gaze at the sky, but I say to you, the only way through the world is to pass through the underground.”![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. This article is also part of The Conversation's series marking 100 years since the death of writer Franz Kafka. These articles explore his legacy and influence on everything from cinema to law. To read more, click here.