In April of 1896, Nova Scotian-born publisher George Munro decamped from New York City to the nearby Catskill Mountains to oversee repairs to his country home there. The next time his family saw him, he was dead.

Munro, who died of heart failure during a post-breakfast walk, was so well known in the United States at the time of his death that the news was splashed across the front page of the New York Times.

‘DEATH OF GEORGE MUNRO’ reads the headline, squeezed between a raft of other news ranging from a revolt in the U.S. Senate and mobs in the streets of Paris to a local robbery gone awry. Munro had built his reputation and a personal fortune in the publishing sector by offering well-known novels, including titles such as Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and George Elliot’s Adam Bede, at affordable prices.

Just over a week later, the newspaper published a follow-up article — this one containing the details of Munro’s will. His wife, two sons, and two daughters were listed as the primary beneficiaries of Munro's estate, which included a collection of properties (an apartment complex named the Dalhousie among them) and financial holdings. Absent from the document were any gifts to public institutions.

To those at Dalhousie familiar with Munro, this last bit may come as a surprise.

Why? Well, Munro was the man who just decades earlier had been so generous to Dalhousie, bequeathing what amounted to $330,000 (about $10 million today) to the school during the 1870s and 1880s to fund a collection of scholarships and professorships that arguably helped save it from closure.

A story about Munro's death positioned high on page one of the April 25, 1896 edition.

“Desperate is not too strong a word for Dalhousie’s financial condition. Talk of closing Dalhousie down was heard on every side," wrote P.B. Waite in the first volume of The Lives of Dalhousie University.

Munro's gifts included money to fund still-existing chairs in Physics, History, English Literature and Rhetoric, Law and Philosophy, as well as bursaries that supported some of Dal’s first female students. Dal's Board of Governors described the bequests as “without parallel in the educational history not of Nova Scotia alone but of the Dominion of Canada.” Munro was also a benefactor to New York University, the Presbyterian church, and other organizations throughout his life.

While many individuals authorize gifts to be executed upon following their death, it seems Munro had preferred to do so himself.

“There are no bequests to public institutions, it having been Mr. Munro's settled policy to be his own executor of such benefactions,” wrote the author of the Times article.

A day to honour the man named Munro

Dalhousie students were so grateful for Munro’s generosity that they lobbied the university’s board to create a day in his honour without classes, a wish that was granted in 1881.

The holiday wasn't always celebrated on the first Friday of February as it is now. When it was first established, The George Munro Memorial Day took place each year on the third Wednesday of January. And, later, in the 1920s, the holidays shifted to the second Tuesday in March "so that students might better enjoy it."

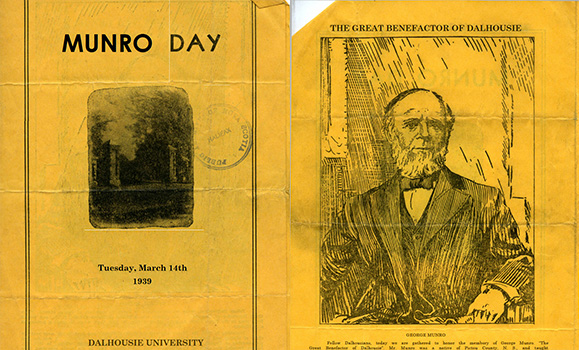

A Munro Day program from 1939 when the holiday was held in March.

In the early decades, Munro Day was filled with Dal-sponsored events, including official lectures and winter sleigh rides to Bedford that befitted the school's small student body at the time. Larger student-led events such as dances and sporting competitions became the norm in the mid-20th century as Dal grew, with ski trips a common outing in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Munro Day lives on now in its own way — there’s a Fast and Furious movie marathon this year and residence activities, for instance — and serves as a welcome mid-winter break from work and class for members of the Dal community.

You could say Munro’s generosity continues to bear fruit a century and half later. And, as this article illustrates, the man is still making headlines.