Astronomers have detected organic molecules in the most distant galaxy to date using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, demonstrating the power of Webb to help understand the complex chemistry that goes hand-in-hand with the birth of new stars even in the earliest periods of the universe’s history.

The molecules — which are found on Earth in smoke, soot and smog — are in a galaxy that formed when the universe was less than 1.5 billion years old, about 10 per cent of its current age.The discovery is significant because it may help scientists understand how stars formed in the earliest stages of the universe and casts doubt on a long-held belief that where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

The international team, including Dalhousie University astrophysicist Scott Chapman and Texas A&M University astronomer Justin Spilker, found the organic molecules (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAH) in a galaxy more than 12 billion light years away. The galaxy was first discovered by the National Science Foundation’s South Pole Telescope in 2013.

The international team, including Dalhousie University astrophysicist Scott Chapman and Texas A&M University astronomer Justin Spilker, found the organic molecules (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAH) in a galaxy more than 12 billion light years away. The galaxy was first discovered by the National Science Foundation’s South Pole Telescope in 2013.

"This galaxy is one of the most luminous in the universe, forming stars at a very high rate — 100s of times more rapidly than our own Milky Way. We were hoping to get new insights in the chemistry of the gas supply for forming stars to understand how galaxies like this are forming stars so rapidly," says Dr. Chapman, pictured above right.

"Thanks to the high-definition images from Webb, we found a lot of regions with PAH or 'smoke,' but no star formation, and others with new stars forming but no smoke. This is very unlike local galaxies — where if there's PAH, there are stars forming."

Einstein ring

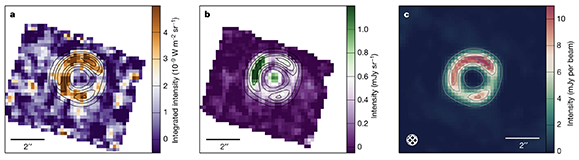

The discovery, published in the journal Nature, was made possible through the combined powers of Webb and fate, with a little help from a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. Lensing, originally predicted by Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, happens when two galaxies are almost perfectly aligned from our point of view on Earth. The light from the background galaxy is stretched and magnified by the foreground galaxy into a ring-like shape, known as an Einstein ring.

"We were amongst the very first users of the new James Webb Space Telescope. Its capabilities allowed us to detect the molecule in a galaxy that is extremely far away from us, and thus seen in the very early universe, not long after the Big Bang," says Dr. Chapman.

"Previously, this molecule had only been detectable in relatively nearby galaxies."

The data from Webb found the telltale signature of large organic molecules akin to smog and smoke — building blocks of the same cancer-causing hydrocarbon emissions on Earth that are key contributors to atmospheric pollution. However, the implications of galactic smoke signals are much less disastrous for their cosmic ecosystems and are quite common in space. It was thought their presence was a sign that new stars were being created.

The new results from Webb show that this idea might not exactly ring true in the early universe.

“Thanks to the high-definition images from Webb, we found a lot of regions with smoke but no star formation, and others with new stars forming but no smoke,” said Dr. Spilker, an assistant professor in the Texas A&M Department of Physics and Astronomy.

A figure included in the Nature study. (Nature)

The power of the Webb

Discoveries like this are precisely what Webb was built to do: understand the earliest stages of the universe in new and exciting ways.

"This was incredibly exciting to get some of the first observations coming off the new JWST.

And extra exciting to see how powerful the telescope is, and how well it works," says Dr. Chapman.

The team, which included dozens of astronomers from around the world, says the discovery is Webb’s first detection of complex molecules in the early universe – a milestone moment seen as a beginning rather than an end.

"Detecting smoke in a galaxy early in the history of the universe? Webb makes this look easy. Now that we’ve shown this is possible for the first time, we’re looking forward to trying to understand whether it’s really true that where there’s smoke, there’s fire," says Dr. Spilker. "The only way to know for sure is to look at more galaxies, hopefully even further away than this one."

JWST is operated by the Space Telescope Science Institute under the management of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc.

Recommended reading: When galaxies collide