About the author: Jamie Snook is an Adjunct in the Marine Affairs Program at Dalhousie University.

Nanuk, the Inuktitut word for polar bear, is an iconic animal, capturing public imaginations and starring in international marketing campaigns. As nanuk has increasingly been used as the poster species for climate change, it has also become separated in the popular imagination from the peoples and communities of the North.

Yet nanuk is a cultural keystone species that provides a sense of identity, spiritual connections, food, livelihoods and cultural continuity throughout Inuit homelands. Polar bears and Inuit continue to share the same lands, waters and ice. They regularly interact on the land during a harvest, and in communities, where nanuk can become a safety issue. This relationship is a part of life in the North and Inuit carry generations of knowledge and science about polar bears.

There are many conflicting views of nanuk. Inuit, researchers, conservationists and others have often been at odds with each other about how polar bear populations should be managed.

As Inuit who work within various co-management boards — public governance institutions that incorporate Inuit knowledge of wildlife and the environment into the decision-making of the provincial, territorial and federal governments — we have interpreted polar bear science, learned from Inuit knowledge and participated in many public policy discussions about nanuk.

Taking care of nanuk

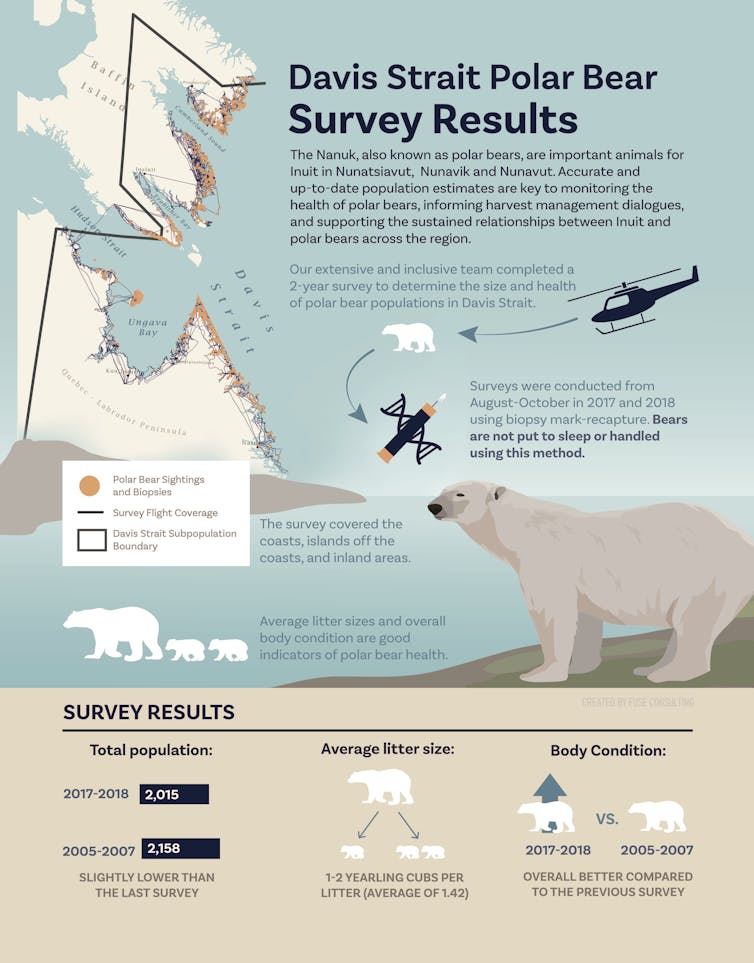

Scientists divide the world’s polar bears into sub-populations, based on what is known about their genetics, movements and other management considerations. Thirteen of the world’s 19 sub-populations of polar bears are found in Canada, putting Canada at the forefront of polar bear research, management, regulation and policy.

Nearly 50 years ago, over-hunting was considered the largest threat to nanuk and international co-operation addressed this issue by placing restrictions on harvesting numbers — some voluntary and others imposed — and increasingly robust rules and regulations. The Government of Canada has collaborated with Greenland, Norway, Russia and the United States on public policy since 1973, when these countries signed the Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears.

The negotiation of land claim agreements starting in 1975, led to the formal implementation of co-management processes across Northern Canada. We have experience on the co-management boards from three different Inuit land claim agreements: Nunavut, Nunavik and Nunatsiavut.

Nanuk co-management

Co-management boards are a shared and independent space where appointees from the federal, provincial, territorial governments and Inuit work with all the available knowledge to make, whenever possible, collaborative decisions about harvest levels and other management recommendations.

Through our work in the Eastern Arctic, representing the Nunavut Agreement (established 1993), the Labrador Inuit Land Claim Agreement (established 2005) and the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement (established 2008), we work directly and regularly on polar bears.

The Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board and the Torngat Wildlife and Plants Co-management Board all have prominent roles in the management of the Davis Strait polar bear population. Simply put, these boards may decide on nanuk harvest levels.

Our organizations play an important role in national and international polar bear management and we bring strong and diverse sciences and knowledges to decision-making tables. We work together to share western science and Inuit knowledge to establish total allowable harvest levels and support polar bear and Inuit health and well-being.

The most recent information combining Inuit knowledge and science on the Davis Strait polar bears indicates that the population levels have remained relatively stable over the past decade at approximately 2,000 animals. Their body conditions have also improved. Over this period, harvesting was also able to increase in this vast region to approximately 100 animals per year. This is a sign that Inuit and nanuk alike have benefited from the past decade of co-management and dialogue among Inuit and different levels of government.

International intentions with unintended consequences

Later this year, the Conference of the Parties for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) will meet in Panama City, Panama. Potential proposals and decisions made there about nanuk could have serious consequences for Inuit.

CITES aims to ensure that the trade in wild animals does not threaten their survival. In 2010 and 2013, the United States brought forward proposals to the parties in Doha, Qatar and Bangkok, Thailand, which, had they been passed, would have generally prohibited the export of valuable polar bears parts such as their skins. International trade would have been permitted only in exceptional circumstances.

If successful, these CITES proposals would have had detrimental and wide-ranging impacts on Inuit culture, livelihoods and well-being. They could have established a scenario similar to the results of the European ban on seal products and the tragic impacts on Inuit rights, livelihoods and well-being. We should know by mid-June 2022 if the United States or another party to CITES plans to bring forward a new proposal.

Inuit culture changes over time. For Inuit today traditional values and activities are increasingly linked to globalization and the international economy through modernization, industrial pressures and the climate crisis.

Decisions made at far away international conferences and through the influences of foreign geopolitics, do not properly consult with Inuit or include Inuit knowledge. Local self-determination may be indirectly altered through new international proposals that may make co-management decisions moot if the policy context changes.

Inuit live with nanuk in their territories and are the primary users and stewards of this species. It is imperative that Inuit involvement in polar bear management remains strong and at the forefront of decisions to support self-determination and the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

This is our call to have Inuit land claim agreements and co-management boards respected by the Canadian government and championed at international forums such as CITES so the global public can be assured that nanuk are in good hands with Inuit stewardship.

The first step in this direction is the understanding on behalf of the scientific and biological communities that Inuit knowledge about nanuk is a deep and generational form of science and essential to be included at all levels of decision-making.

The negotiation of these governance structures in Canada took half a century and we are now many decades into their implementation. No one cares more about nanuk than Inuit, and Inuit will continue being experts in polar bear relationships. While including Inuit in national and international decision-making processes has improved, ensuring thriving polar bear and Inuit populations alike will require trust in co-management decision-making, Inuit self-determination and Inuit ways of being with nanuk.

This article was co-authored by Jason Akearok, executive director of the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, and Tommy Palliser, executive director of the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.