Megan Aston is a Professor in the School of Nursing at Dalhousie University, Phillip Joy is an Assistant Professor in Applied Human Nutrition at Mount Saint Vincent University, and Andrew Thomas is a Research Assistant in Applied Human Nutrition at Mount Saint Vincent University.

Compassion is more than being nice and can be viewed in many different ways. Philosophers, religious leaders and scientists from different parts of the world have all discussed the meanings of compassion within their own contexts. It can be described as a distinct emotion, a virtue or a way of life that recognizes the pain and suffering of others. Compassion can be a means to self-healing and feeling our common humanity.

But compassion is also action: a “form of engagement with the world.” Compassion has the potential to positively transform social systems or the potential to reinforce current beliefs that can separate people.

Some have even critiqued the concept of compassion, particularly from a Western perspective, as an emotion that is focused on oneself and leads to the comparisons of the self with others.

Within Western health-care systems, there is growing recognition that compassion is an essential component for positive health and well-being. There have been calls for compassion to be a greater part of the care processes of health professions and the training of health professionals.

Researchers have shown that as little as 40 seconds of compassion have made positive differences in patients’ experiences and health. In those 40 seconds, compassion can be expressed by acknowledging patient concerns, showing support, acting as a partner and validating emotions.

Compassion and health care for 2SLGBTQ+ people

Accessing and receiving compassionate health care, however, is often not possible for many groups, including Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and other sexual identities, such as pansexual or asexual (2SLGBTQ+) individuals.

Heteronormativity — the assumption that all people are straight — and cis-normativity — the assumption that all people are distinctly either a man or a woman — create many health disparities for 2SLGBTQ+ people. They also create barriers to accessing safe and inclusive care.

Heteronormativity and cis-normativity can lead to fear, ignorance, prejudice and acts of violence towards 2SLGBTQ+ in Canada. Research has shown that education on these topics during training for health-care professionals is beneficial, but physicians have reported a lack of advanced knowledge on 2SLGBTQ+ issues. There is a growing recognition for the need of more 2SLGBTQ+ health training and more funding for 2SLGBTQ+ health research.

Transformative compassion study

The aim of our forthcoming research, to be published in the journal Qualitative Health Research, was to explore the meanings of compassion for 2SLGBTQ+ individuals.

In our study — carried out at Mount Saint Vincent University — we talked with 20 self-identifying 2SLGBTQ+ people from across Canada. In online interviews, we asked them to share experiences of compassion (or non-compassion) and to tell us about their beliefs and values about compassion. Many of the things our participants shared were about compassion and health.

In our findings, we explored the meanings and expectations of compassion in health care for our participants. As one them said: “Good health care has to have compassion at the core.” Several of our participants noted that comfort, safety, inclusive language and awareness and understanding of the shared trauma that many 2SLGBTQ+ individuals suffer are essential components for health care to be compassionate.

Compassionate health care is not guaranteed

Another participant believed that when “…you’re accessing the health-care system you would expect compassion from the health-care system. I know a lot of people, queer or not, don’t have that experience. Compassion isn’t guaranteed in health care, but when it’s found it’s celebrated.”

For example, this participant described their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in which their doctor showed compassion to them by including their partner:

“COVID brought out this huge experience of shared humanity among all kinds of different people… a lot of compassion showed through in those first early months, where we’re all in this together.”

Compassionate comics

We wanted to share the beliefs and experiences expressed in the study as a means to start conversations about compassion, and to work towards creating awareness about the power of compassion to positively transform the lives, health and well-being. We have previously used comics as a means to share our research, and chose to do so again.

To create our compassionate comics, we enlisted the talents of 12 2SLGBTQ+ artists from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom and Greece. We asked each of them to illustrate stories told by our participants.

For example, a few participants used the HIV/AIDS crisis as an historic example of both the non-compassion in the health-care system and the power of compassion to change systems.

As one participant related:

“When I was in my 20s, the AIDS crisis was at its peak, and although in the long run I think that inspired compassion among the general public, at the time there was a lot of negativity. A lot of blaming of people, blaming of behaviours. A lot of religious nastiness. So, over time that has changed and I think media had a lot to do with it. And the organization of the queer community during the AIDS crisis — and I think more visibility — humanized people to the general public in a way that hadn’t happened before.”

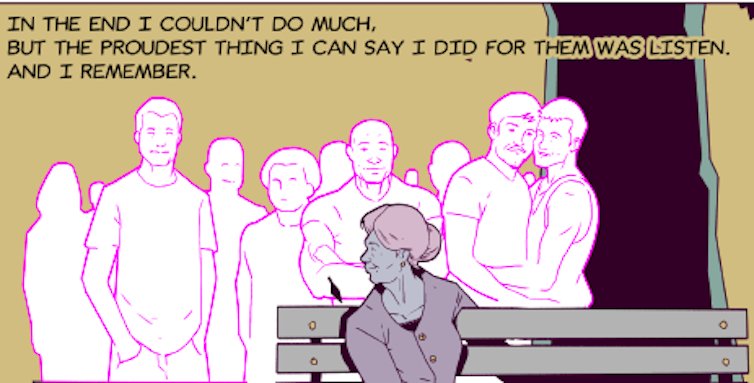

This story is reflected in a comic entitled “Remember” by Canadian artist David Winters. In the 10-page story, a nurse walks through a crowd of anti-gay protesters outside her hospital to go to work. She shows compassion to a dying man by listening and showing understanding to him when others did not.

Our study results are reflective of only a few voices from the 2SLGBTQ+ umbrella, so we cannot make overarching generalizations. However, we can suggest that compassion was seen as a central and critical component for good care.

We suggest that in order to truly transform health care, we must examine and challenge assumptions of sexuality and gender in health-care practices and systems. Doing this will help all people feel comfort, safety and understanding — in other words, compassion.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.