For many Canadians, the COVID-19 pandemic has been experienced primarily as a public-health ordeal. But for a huge number of others who call the country home, the crisis has coincided with another troubling threat: growing race-based hate.

Incidents of anti-Asian racism skyrocketed across Canada during the pandemic. A federally funded March 2021 report released by advocacy groups paints a grim picture, citing 1,150 cases of racist attacks against Asians in Canada between March 2020 and February 2021. The problem appears especially severe in certain communities such as Vancouver. Police statistics there show a 717-percent rise in hate crimes directed at individuals of East Asian ancestry from 2019-2020.

Tackling the problem — which has been around since immigrants from the region first arrived in Canada in the late 1800s — is at the heart of this year’s theme for Asian Heritage Month in Canada: Recognition, Resilience, and Resolve. Marked each May, the month presents an opportunity to celebrate the heritage of Asian Canadians but also to cast a critical eye on how members of that community are represented in history and treated in the present.

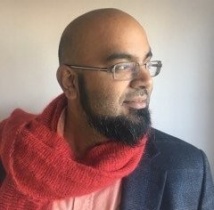

We spoke to Ajay Parasram, an assistant professor in the departments of International Development Studies and History, about Asian Heritage Month, the history of anti-Asian racism in Canada and ways people can help help combat it.

What is a surprising event or aspect of Asian Canadian history that people might be surprised to learn about?

In August 1907, the Canadian chapter of the Asiatic Exclusion League was formed, bringing together white supremacists from trade unions, churches, and white citizenry more generally in Vancouver to agitate for an end to all immigration of people from Asia. The white supremacists rioted in Chinatown for days before the police intervened, which shows the value the state placed on Asian lives. As Chinatown burned, the mob turned to Japantown, but the Japanese had seen what was happening and armed themselves. At the same time South and East Asians were walking into British Columbia from Washington State as anti-Asian riots were raging on the U.S. side of the border, too.

In August 1907, the Canadian chapter of the Asiatic Exclusion League was formed, bringing together white supremacists from trade unions, churches, and white citizenry more generally in Vancouver to agitate for an end to all immigration of people from Asia. The white supremacists rioted in Chinatown for days before the police intervened, which shows the value the state placed on Asian lives. As Chinatown burned, the mob turned to Japantown, but the Japanese had seen what was happening and armed themselves. At the same time South and East Asians were walking into British Columbia from Washington State as anti-Asian riots were raging on the U.S. side of the border, too.

This period of Asian Canadian history is important because it shows how across various Asian nationalities, direct and often lawful white supremacy (as evidenced in laws like the Chinese Head Taxes, the Continuous Journey Regulation, or later Japanese internment) needs to be historicized by looking at what the source of the violence was — white supremacy.

Why is May the month that we celebrate Asian heritage in Canada?

Twenty years ago, Canada’s first Senator of Asian ancestry, Dr. Vivienne Poy, introduced a motion in the Senate that Canada recognize the contributions of people of Asian ancestry to Canada and it was officially adopted and designated as May in 2002. I don’t really know why May was chosen, but according to Dr. Poy, May was already being used as an opportunity to celebrate in different regional contexts, particularly in the West Coast, and also in the United States.

There’s lots to celebrate about Asian resilience across the many different waves of migration and arrival in Canada, but part of the problem has been the thinness of how we engage the history. Canada generally wants samosas and eggrolls and a cheerful traditional dance, but does very little to deepen the meaning of diversity and decolonization.

Anti-Asian racism has been around for generations, but some recent high-profile violent examples in North America have been especially disturbing. What, if anything, is different about these recent events?

They differ mostly in terms of what society is now willing to tolerate. We’re not likely to see a white supremacist mob setting Chinatowns across the country ablaze while the state quietly cheers them on, but we will allow Asian-Canadians to feel increasingly vilified in their homes and communities and to be displaced by seemingly “neutral” market processes like gentrification and urban development. I guess this is a kind of progress, but we can do better. The kinds of attacks Asian-Canadians, and especially people who are perceived to be East Asian, have endured since COVID include being deliberately coughed and spit at, which seems small, until you consider that in the context of a global pandemic this is a desire to wage biological forms of assault.

There's been a robust chain of anti-Asian racism in this country for about as long as Confederation. It has relied on unfounded colonial assumptions about hygiene, disease, infections, and metaphors with invasion that serves two related purpose. The first is to viify Asian migrants as well as other non-white people, and the second is to “exalt” (to borrow from Asian-Canadian scholar Sunera Thobani) white people as the ideal and natural political subject of Canada. These twin purposes have been more foundational than hockey in the forming of Canada, in large part because it also contributes to the attempted genocide and ongoing efforts to degrade or erase Indigenous sovereignty across the continent. While these racist tropes have existed since the 19th century, we needn’t go back to the 19th century to see evidence of this kind of violence in Canadian cities, as anti-Asian racism during the SARS and H1N1 Pandemics have shown us in this century alone.

In the spirit of this year's theme, "Recognition, Resilience, and Resolve," what advice would you provide for people looking to help break down the structures of anti-Asian racism?

Canada presents itself as a multicultural “mosaic” in contrast to the United States “melting pot.” But as my partner, Fazeela Jiwa, has insightfully described, let’s not forget that a mosaic still has a rigid border that establishes the parameters of what is possible to present within the piece of art. In Canada, this border remains structural white supremacy, which has never been dismantled but only transformed and swept under the rug when named. If Canada has the desire to dismantle the structures of anti-Asian racism – and I believe that the vast majority of Canadians do – then it cannot be done in isolation from all forms of racism, including ongoing settler-colonialism of which many Asians are also complacent. My advice to everyone is to stop looking to communities that experience racism for the solutions to ending racism and turn that attention to the root cause: structural white supremacy. I’m not talking about Nazis in the street, although obviously that’s a problem too. I’m talking about the legacy impact of colonial laws and sensibilities that continue to “border” the mosaic. Only through directly confronting these deep colonial continuities within the nation-state can we hope to break down these structures.