About the authors: Lucia Fanning is Professor Emerita in the Marine Affairs Program at Dalhousie University. Shelley Denny is an IDPhD candidate in the Marine Affairs Program at Dalhousie University.

In the past month, the Sipekne’katik First Nation and the Potlotek First Nation placed lobster traps in bays at the opposite ends of Nova Scotia. Each community had developed a management plan based on their treaty rights to earn a moderate livelihood.

The response to these actions by non-Indigenous fishers has led to national and international coverage of the ensuing violence, including damage to property and assault. Both non-Indigenous fishers and the Fisheries Department (DFO) have since seized some of the lobster traps.

The conflict has largely centred on whether the lobster stock is threatened by out-of-season fishing, and the definition of a “moderate” livelihood. However, this focus misses the root of the Mi’kmaw livelihood issue, namely the question of who has the authority to govern livelihood activities and how it is done.

Researching the issue

We’re part of a small group that has been examining these very issues since 2014, and includes scholars with expertise in ocean governance and marine policy and colleagues from the Assembly of First Nations. Our research project, Fish-WIKS, aims to understand how Indigenous and western knowledge systems can be used to improve the sustainability of Canadian fisheries.

The processes that feed into decision-making in fisheries in Canada have been primarily influenced by western science‐based knowledge systems that focus on a reductionist approach to understanding problems. In contrast, Indigenous ways of knowing are based on world views and values that are integrative and holistic, or as Elder Albert Marshall of Eskasoni First Nation once spelled out, “wholistic.”

Read more: It's taken thousands of years, but Western science is finally catching up to Traditional Knowledge

Who would have guessed that our results from examining an alternative governance structure for the livelihood fishery in Nova Scotia through the lens of both knowledge systems, referred to as “two-eyed seeing,” would coincide with the current conflict playing out in the lobster fishery?

Two-eyed seeing

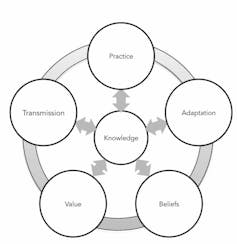

In two-eyed seeing, knowledge is viewed as a system that comprises what is known and how it is known. But a knowledge system, whether western or Indigenous, is composed of many things.

What we know, how we practise our knowledge, how we adapt to it and how we transmit and share knowledge are the more familiar elements. But the values and beliefs that underpin these elements, and which actually distinguish one knowledge system from another, are often ignored.

This is a problem because the values and beliefs underpinning one system are often at odds with those of another system, potentially creating a barrier to collaboration. However, the Fish-WIKS projects showed there are similarities that can bridge these knowledge systems and lead to greater understanding of the differences.

Governance gaps

Our research identified a number of gaps in governance that have contributed to the lobster fishery situation we have today.

There is still no federal policy to address livelihood fisheries and the issue of livelihood as a treaty right is not mentioned in the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy, the primary policy guiding the federal response to Indigenous fisheries

There are also conflicting views on who has the authority to manage fisheries, which stem from the perceived legitimacy of each governing system. Legitimacy influences whether a political action is perceived as right or just by those who are involved, interested and/or affected by it.

The two sets of rules for fisheries arise from the protection of Aboriginal and treaty rights in sections 25 and 35 of the Constitution, complicating the issue of legitimacy. This legal pluralism gives DFO the authority over non-Indigenous commercial fisheries while limiting its capacity to govern Indigenous fisheries.

In addition, Canada must justify any limits it places on the rights of Indigenous people engaged in fishing practices, as determined by the Supreme Court of Canada in R. vs. Sparrow in 1990. The court also affirmed Miʼkmaw treaty rights in R. vs. Simon in 1985 and R. vs. Marshall in 1999.

Our research confirms that Mi’kmaq are aware of challenges with the exercise of treaty rights and supports the necessity for Mi’kmaq to develop fishery and fishing rules that are legitimate in the eyes of Mi’kmaw fishers, non-Indigenous fishers and DFO. Some communities have developed such rules, incorporating knowledge from both western and Indigenous systems.

However, the question remains, does DFO have the justification to intervene with Mi’kmaw lobster livelihood fishing practices if, as Dalhousie University fisheries expert Megan Bailey pointed out, there is no scientific evidence that the current practice of the lobster livelihood fishery threatens the sustainability of the stock?

Read more: Nova Scotia lobster dispute: Mi’kmaw fishery isn't a threat to conservation, say scientists

This needs to be cleared up. The Fisheries Act gives the DFO broad regulatory authority and this may extend to Indigenous fisheries. But the Marshall decision narrows that authority to apply only “where justification is shown.”

Moving forward

Canadians need to recognize that this current conflict playing out in Nova Scotia represents not only an operational nightmare for DFO but is a deep-seated governance issue. It requires developing a mechanism by which Mi’kmaq can legitimately contribute to the governance of fisheries as an integrated whole.

Short-term solutions will be identified, but a longer-term solution must address the legal pluralism that exists in Canada and facilitate the adoption of other forms of governance models in which DFO does not have exclusive authority.

The current focus on the lobster livelihood fishery and finding a dollar definition for “moderate” misses the fact that the underlying governance gap is the crux of the issue.![]()

This article was first published on The Conversation, which features includes relevant and informed articles written by researchers and academics in their areas of expertise and edited by experienced journalists.

Dalhousie University is a founding partner of The Conversation Canada, an online media outlet providing independent, high-quality explanatory journalism. Originally established in Australia in 2011, it has had more than 85 commissioning editors and 30,000-plus academics register as contributors. A full list of articles written by Dalhousie academics can be found on the Conversation Canada website.