Pride as we know it today looks a lot different than when it first emerged back in the late 1960s as a protest for equality and recognition. Today, Pride is marked by a month of festivals, events and parades that celebrate and show support for LGBTQ2SIA+ communities.

As this year marks the 50th anniversary of the first Pride parade (held in New York City), we spoke to Matt Numer, an associate professor and head of the Division of Health Promotion in the School of Health and Human Performance and an advocate for LGBTQ2SIA+ health issues, about the history of Pride and why it is still so important to celebrate today.

Can you tell us a bit about the history of Pride and how it has evolved over the decades?

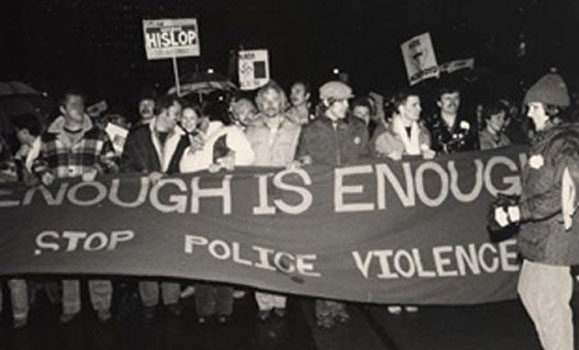

Pride started as a form of protest against fairly overt oppression, primarily from the police, I would say. We saw a lot of issues decades ago with police attempting to out people, arrest people for engaging in what at the time they called “homosexual activities.” People are pretty familiar with the rise of the gay rights movement with the Stonewall Riots, when police attempted to raid bars. What they would do is they would go in and they would particularly target people transgressing gender norms. Today, we might call them drag queens; the way we define people has also evolved over the years. But they would drag people out and publish their names and attempt to have them fired, and all sorts of things like that. In Canada, you had the bath house raids in Toronto, where they would go and purposefully target people engaged in sex activities. Out of that, Pride became a protest — a march very similar to the protests we see today with the Black Lives Matter movement. I think that’s where it gets its historical roots.

Pride started as a form of protest against fairly overt oppression, primarily from the police, I would say. We saw a lot of issues decades ago with police attempting to out people, arrest people for engaging in what at the time they called “homosexual activities.” People are pretty familiar with the rise of the gay rights movement with the Stonewall Riots, when police attempted to raid bars. What they would do is they would go in and they would particularly target people transgressing gender norms. Today, we might call them drag queens; the way we define people has also evolved over the years. But they would drag people out and publish their names and attempt to have them fired, and all sorts of things like that. In Canada, you had the bath house raids in Toronto, where they would go and purposefully target people engaged in sex activities. Out of that, Pride became a protest — a march very similar to the protests we see today with the Black Lives Matter movement. I think that’s where it gets its historical roots.

How has it evolved? I think in many ways Pride is still a form of protest and a form of garnering attention, though it may not necessarily be for the same cause and it may take on different forms today. Today, when we think of Pride, most people just think of the celebration, parties, drinking, the parade in particular. But it is still calling attention to the fact that there’s a community of people out there who have been historically marginalized and continue to be in many ways. Pride is the opportunity today for many allies to come out and show their support for us to make queer identities visible to youth. A big way that oppression works is to hide how people are marginalized. Growing up, I didn’t really know many gay people. They were just seen as so outlandish in the eyes of the general population, unless it was something like arrests and protests and stuff like that.

A gay rights demonstration in Toronto, circa 1980s. (Courtesy Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives)

A gay rights demonstration in Toronto, circa 1980s. (Courtesy Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives)

What are some of the unique challenges experienced by LGBTQ2SIA+ communities today and how does Pride bring recognition to those issues?

Pride is also a way for us to see issues that may not be immediately visible. So, you’ll often see different groups marching in the Pride parade. Today it has become very corporatized with the banks and other companies pay their employees to go march in the parade — which, don’t get me wrong, I’m glad that we have corporate support, but that’s not really what Pride is about. But you will see other community groups marching in the parade. They give rise and give light to issues that may not be visible in the Canadian context. There’s a queer Arabs group, Rainbow Refugees — an organization that attempts to help people who have suffered because of their sexual orientation or gender identity to emigrate to Canada. Pride Health is a group through Nova Scotia Health Authority that looks at the disparities in health that emerge for people with queer identities.

Pride is also a time when you can typically get attention from government and media. For many organizations, it’s a time when they show that support. I know from my own advocacy work that when we can raise issues close to Pride they tend to get more attention than during the rest of the year. Governments are fairly dismissive until there is political expediency for them.

What can governments, workplaces, community groups and the general public do to support LGBTQ2SIA+ communities and address these unique challenges?

Money speaks. When governments and organizations are investing in the health and well-being of queer people, then we may start to address some of the health disparities. I think that we still haven’t done a good job of that. On the surface, we think that because we’ve got gay marriage that everything has been solved in Canada, but actually we have greater issues related to mental health, suicide, substance use and things of that nature. That isn’t a product of being gay or queer — that’s a product of a homophobic society. Those are more difficult issues to get at and what we need is a commitment from government to invest more substantively in things like Pride Health, the Youth Project, access to medications. My own advocacy work has a lot to do with HIV prevention and there’s a drug out there that can prevent it almost 100 per cent, but many people don’t have access to it because it’s expensive. The Government of Nova Scotia has refused to pay for it, while about half of Canada’s other provinces have.