About the author: Larry Hughes is a professor and founding fellow of the MacEachen Institute for Public Policy and Governance at Dalhousie University.

From forest fires in Siberia to record-high temperatures in Alaska to the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, 2019 has seen the mounting evidence of climate change.

With climate change being one of the top issues in the federal election, we need to take a look at what effective emissions reduction policies look like.

The party platforms differ substantially on their strategies to reduce emissions. During the English language debate, party leaders discussed their policies on oil and gas extraction, home retrofits and transportation, among others. The range of possibilities spanned from doing very little (Conservative) to aggressive (NDP and Green), and in between (Liberal).

Energy and emissions in Canada

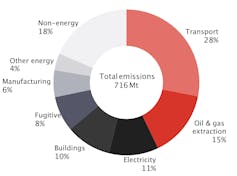

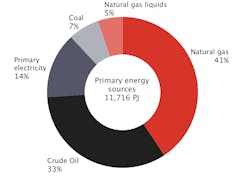

In 2017, more than 80 per cent of Canada’s human-made (anthropogenic) greenhouse gas emissions were from the extraction, conversion and consumption of energy derived from fossil fuels, primarily natural gas and crude oil.

Limiting global temperatures to 1.5C this century will require net-global emissions to reach zero by no later than 2055.

Since Canada is a signatory to the Paris climate agreement, the federal, provincial and territorial governments need policies that reduce energy-related emissions rapidly, yet are both politically and economically palatable.

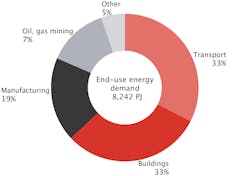

These policies will need to target the different energy systems found across the country: the primary energy supply (more than 80 per cent supplied from sources of crude oil, natural gas, coal, and natural gas liquids); the energy conversion processes (thermal power plants and refineries); the distribution processes and the end-use sectors (industry, transportation, buildings and agriculture/forestry).

Emissions reduction policies

Broadly speaking, there are three categories of energy policy that can be used to reduce emissions: reduction, replacement and restriction.

Reduction

These policies aim to reduce energy demand without changing the system or its energy supply. If the policy leads drivers to take fewer trips or use less fuel, it has done its job.

Read more: Here's what the carbon tax means for you

Other examples of reduction policies include financial incentives to reduce energy demand, such as encouraging building retrofits through grants and low-cost loans and reducing heat losses from industrial processes.

Replacement

These policies aim to change our energy sources or parts of our energy system to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They can be focused on parts of the energy system, like replacing incandescent bulbs with light-emitting diodes (LEDs) or conventional vehicles with hybrid-electric vehicles.

They can also focus on the sources of the energy being consumed, like replacing coal with co-fired coal and biomass in a thermal generating station or substituting petroleum transportation fuels with mixtures of petroleum and biofuel.

Restriction

These policies are a more aggressive type of replacement policy. They target parts of the energy system and the energy it consumes, replacing them with new processes and energy sources to meet existing demand.

For example, the transition from coal to natural gas and renewables in Ontario to improve air quality is an example of a restriction where thermal plants operating with coal were shuttered in favour of new natural gas, solar and wind facilities. Restrictions can also apply to end-use sectors, such as consumers opting to buy electric vehicles rather than conventional petroleum vehicles.

Read more: When it comes to vehicles, Canada tops the charts for poor fuel economy

Emissions reduction and energy security

Developing and implementing the necessary emissions-reduction policies for a rapid decline in emissions is challenging, since these policies will impact every sector of Canadian society.

This can be seen in the five provinces that are subject to the federal government’s carbon-pricing system, which targets energy-use in all sectors of the economy: industrial, transportation, residential and commercial buildings and agriculture.

To be acceptable, the policies must be implemented with minimal risk to the supply and price of energy to Canadians and the Canadian economy. However, policies that are ill-conceived or poorly implemented can inadvertently increase the risks to the energy security of an energy system.

An energy system is said to be energy secure if it is resilient to risks from events caused by human activities, natural disasters, structural failures and policy changes. Secure systems are able to maintain the availability and affordability of the energy consumed by the end-users.

The world has seen several recent examples of energy systems that are not resilient. In 2011, an earthquake and tsunami caused a nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan affected both the affordability and availability of electricity. The risk of downed lines causing fires forced Pacific Gas and Electric to cut electricity supply to 800,000 customers in California. Similarly, the rapid increase in gasoline prices in 2008 affected the commuting habits of many Canadians.

With each disruption, the energy system must adapt to the new conditions to remain secure. Adaptation can, in turn, be a risk to the availability and affordability of the energy supplied to the jurisdiction.

If we look at the major parties’ approaches to this conundrum, we find several trade-offs.

The Conservative Party’s strategy of moving ahead with greenhouse gas intensive oil and gas projects does have the benefit of mitigating the risks of availability and affordability for consumers, but comes with serious long-term climate change risks.

The Greens and the NDP present the opposite option, with action on climate change coming at the expense of energy security.

The Liberals lie somewhere in the middle. They are offering some climate action, but meaningful risks to both energy security — from higher carbon pricing — and long-term climate change impacts — from continued expansion of oil and gas extraction — remain.

The climate-action backlash

Canada currently relies on emissions intensive energy sources. If we are to achieve our emissions reductions targets by 2055, reduction policies will likely have an impact on the availability and affordability of energy.

We have already seen examples of politicians ignoring or scrapping existing emission reduction policies and groups affected by the policies pushing back against them.

In the United States, the Trump administration is reversing many climate regulations, and in France, the unequal application of climate policy was one of the main reasons the yellow-vest movement was formed.

While in Canada, Conservative premiers are pushing back against the federal government’s carbon-pricing policies.

Read more: The Doug Ford doctrine: Short-term gain for long-term pain

So what is the climate-conscious voter to do?

They should look for details on how each party plans to transform the energy system and its impact on their province. This means understanding how electricity is generated, how buildings are heated and cooled, and how goods and people are moved.

In Monday’s debate, the prime minister said, “We recognize that transition to clean energy will not happen overnight.”

While undoubtedly true, one is left with the question, how many nights do we have?

This article was first published on The Conversation, which features includes relevant and informed articles written by researchers and academics in their areas of expertise and edited by experienced journalists.

Dalhousie University is a founding partner of The Conversation Canada, an online media outlet providing independent, high-quality explanatory journalism. Originally established in Australia in 2011, it has had more than 85 commissioning editors and 30,000-plus academics register as contributors. A full list of articles written by Dalhousie academics can be found on the Conversation Canada website.