A new study by geologists in Canada and the United States suggests a repository of precious metals may be locked deep below the moon’s surface.

James Brenan, a professor at the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Dalhousie and lead author of the study in Nature Geoscience, says he and fellow researchers were able to draw parallels between mineral deposits found on Earth and the moon.

“We have been able to link the sulfur content of lunar volcanic rocks to the presence of iron sulfide deep inside the moon,” said Dr. Brenan, who collaborated with geologists at Carleton University and the Geophysical Laboratory in Washington, D.C. for the paper that was published on Aug. 19.

“Examination of mineral deposits on Earth suggests that iron sulfide is a great place to store precious metals, like platinum and palladium.”

Under the moon’s surface

Geologists have long speculated that the moon was formed by the impact of a massive planet-sized object from the Earth 4.5 billion years ago. Because of that common history, it is believed that the two bodies have a similar composition. Early measurements of the precious metal concentrations in lunar volcanic rocks done in 2006, however, showed unusually low levels, raising a question that has perplexed scientists for more than a decade as to why there was so little.

Dr. Brenan says it had been thought that those low levels reflected a general depletion of the precious metals in the moon as a whole.

This new research, which was funded with the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, offers an explanation on the surprisingly low levels and adds valuable insight into the composition of the moon.

“Our results show that sulfur in lunar volcanic rocks is a fingerprint for the presence of iron sulfide in the rocky interior of the moon, which is where we think the precious metals were left behind when the lavas were created,” he says.

A scientific recreation

Dr. Brenan, along with colleagues Jim Mungall of Carleton University and Neil Bennett formerly of the Geophysical Laboratory, did experiments to recreate the extreme pressure and temperature of the lunar interior to determine how much iron sulfide would form.

They measured the composition of the resulting rock and iron sulfide and confirmed that the precious metals would be bound up by the iron sulfide, making them unavailable to the magmas that flowed out onto the lunar surface.

Dr. Brenan clarified that there was likely not enough to form an ore deposit, Brenan “but certainly enough to explain the low levels in the lunar lavas.”

Dr. Brenan says they will require samples from the deep, rocky part of the moon where the lunar lavas originated in order to confirm their findings.

Un-forged territory

Geologists have access to scientific samples from hundreds of kilometres deep inside the Earth, but such material has not yet been recovered from the moon.

“We have been scouring the Earth’s surface for a fairly long period of time, so we have a pretty good idea of its composition, but with the moon that’s not so at all,” he said.

“We have a grand total of 400 kilograms of sample that was brought back by the Apollo and lunar missions… it’s a pretty small amount of material. So, in order to find out anything about the interior of the moon we have to kind of reverse engineer the composition of the lavas that come onto the surface.”

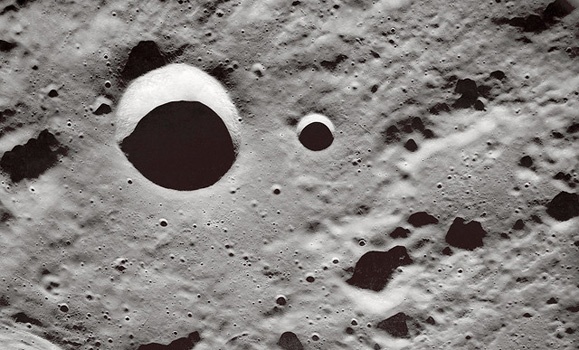

Remote sensing by satellites suggest there may be outcroppings of the deeper parts of the moon, revealed after massive impacts formed the Schrödinger and Zeeman craters in the South Pole Aitken basin.

“It’s pretty exciting to think that we might return to the moon,” says Dr. Brenan. “And if so, the South Pole seems like a good choice for sampling.”