Every Thursday afternoon over the winter term a team of first-year science students could be found in the Tissue Mechanics Lab at Dalhousie’s School of Biomedical Engineering, huddled over the work bench with focus and determination.

They’ve been preparing tiny patches of cow heart tissue and running them through experiments. Why? To answer this question: is heart valve remodelling during pregnancy reversed post-partum?

Cutting-edge science

“When a woman gets pregnant, there's a greater volume of blood that needs to pump through the heart to support the fetus and its organs,” explains Meghan Hamilton, a first-year student working in the Tissue Mechanics Lab through the Dalhousie Integrated Science Program (DISP). “To keep up with an increase of almost 50 per cent more blood flow, the cardiovascular tissue has to adapt and remodel.”

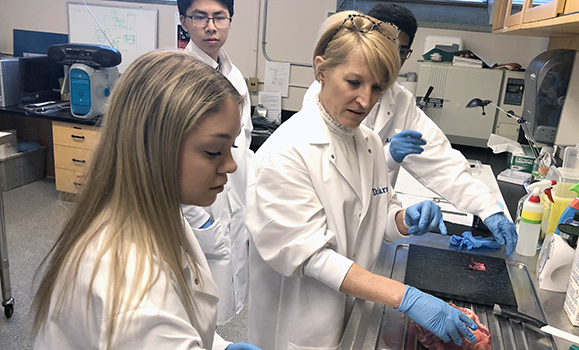

Meghan Hamilton (left) and classmate Sofia Nicolls (right) working in the Tissue Mechanics Lab.

Meghan, along with four other DISP students, were working under the supervision of associate professor Sarah Wells and fourth-year honours biology student Meghan Martin.

Since 2012, Dr. Wells has been collecting cow hearts from abattoirs — by-products of the beef industry that would otherwise be discarded — to examine how hearts adapt to an “increased mechanical load” of blood during pregnancy.

“A pregnant woman’s heart undergoes remarkable physical and structural changes,” explains Dr. Wells, the assistant dean of the Medical Sciences program and associate professor of both biomedical engineering and physics. “Their heart valves expand quickly during early stages of pregnancy. Those same changes look just like cardiovascular disease in other patients.”

Dr. Sarah Wells (right).

Research exposure

The Dalhousie Integrated Science Program (DISP) is a first-year option for Bachelor of Science students that want to jumpstart their exploration of the sciences with hands-on experience conducting studies in labs and out in the field.

Every April, DISP students present their own scientific studies at a year-end research symposium and poster session on campus. These studies — conducted in small groups over the winter term under the supervision of established researchers — expose students to the integrated nature of scientific research.

For DISP student Jade O’Donnell, learning how to run a study that combines physics, engineering, and medicine in the Tissue Mechanics Lab has been a fascinating experience — one that has opened her eyes to a potential career path.

“I didn’t know about biomedical engineering before, but I’m really interested in it now because it’s a mix of so many fields,” says Jade. “I heard Dr. Wells give a guest lecture once and that’s when I knew I had to meet her to learn more about this work.”

Discovering answers

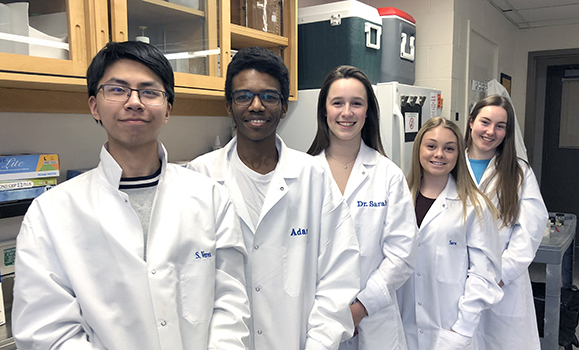

Meghan H. and Jade join Sofia Nicolls, Kareem Abdulla and Joey Lo to make up the DISP student research team tasked with helping Dr. Wells. Together they aimed to answer a burning question among biomedical engineers and medical researchers alike: do mom’s heart valves return to the size they once were after her baby is born? This research team didn’t think so.

Left to right: Joey Lo, Kareem Abdulla, Meghan Hamilton, Jade O'Donnell, Sofia Nicolls.

To prove their hypothesis, the students used a variety of methods that examined the collagen proteins within tissue samples and compared the surface area of heart valves from both pregnant and non-pregnant cows.

“Their findings suggest that heart valve remodelling is not reversed after pregnancy,” says Dr. Wells. “In animals that have had previous pregnancies, valve leaflets were much larger than in animals that have never been pregnant. The thermomechanical properties of the collagen are also very different, suggesting that the molecular structure of the collagen itself is changed.”

The students presented their findings at the DISP Research Symposium on Thursday, April 4 before displaying their work in a poster session tomorrow (April 5) from 2:30-5 p.m. in the third-floor lobby of the Life Science Centre. All are welcome to attend.

This year, 29 research projects will be showcased thanks to supervisors from Dal, the National Research Council, and the Bedford Institute of Oceanography agreeing to take on first-year science student research teams. Topics include battery science, changing marine conditions and ecosystems, machine learning, literacy in school-aged children, and more.

Read about all of this year's DISP projects at the Faculty of Science website.