For more than 70 years, the United Nations has linked the many countries of the world together through its extensive patchwork of conventions, treaties, agencies and decision-making structures.

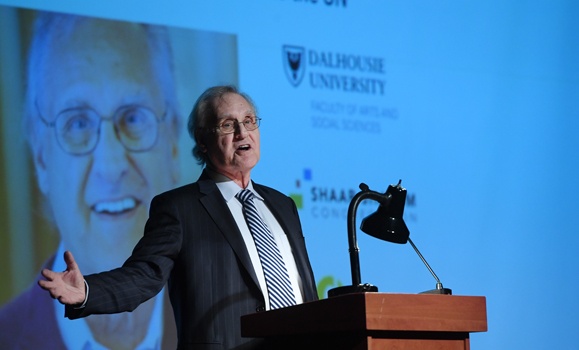

But politics and pessimism increasingly threaten to undermine the global body’s ability to act in the face of pressing crises and concerns, said Canadian humanitarian Stephen Lewis in the Shaar Shalom lecture at Dalhousie earlier this month.

The United States has actively disengaged from the organization, failing to even send a new ambassador after the last one’s term ended, he noted. And nationalists around the world consistently question the organization’s very political legitimacy. Meanwhile, humanitarians have grown particularly frustrated with the paralysis of the UN’s political wing.

“That is where much of the disaffection and much of the public concern stems from,” he said, referring to the Secretary General, Security Council and General Assembly. “It’s obvious that we grind down in a kind of abattoir of inflexibility when dealing with tremendous human concerns.”

More than 600 people turned out to the McInnes Room in the Student Union Building for Lewis’s talk, an annual event established by the Shaar Shalom Synagogue and Dal’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences as a way to explore the broad themes of tolerance, multiculturalism and diversity.

Lewis touched on a wide range of critical issues on which the UN has failed to show leadership in recent years, including climate change, mass migration, natural disasters and humanitarian crises in countries such as Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Venezuala and Myanmar.

Lewis, who served for years as Canada’s ambassador to the UN and in various senior roles in the organization, painted a picture of a global body desperately in need of strong moral leadership.

“We need leaders who are not afraid to take on issues that are disputatious and where there will be disagreement, but where principle will ultimately prevail because they gather around them a sonorous voice of agreement. It is so desperately required,” he said.

He said Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has spoken out on some of the critical issues but doesn’t seem to have the “gravitas” or influence to “bring other countries into the fold.”

Further complicating Canada’s ability to provide independent leadership at the UN is the country’s current campaign to secure a seat on the Security Council in the 2020 elections, said Lewis.

“Everything we do is premised on whether or not our positions will enhance our opportunity to be elected to the Security Council,” he said, calling it an “obsession.”

The "other" United Nations

Lewis tempered his pessimism slightly when he spoke about the work of the “whole other half of the United Nations” that people sometimes forget about — namely funds, programs and agencies such as the United Nations Development Program, the World Health Organization and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), where Lewis spent four years as deputy executive director in the mid-to-late 1990s.

“I have to say these funds and programs do magnificent work and they uphold the conventions [such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for instance] which countries so often ignore,” said Lewis, who also spent five years as the Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa.

“And if and when you’re traveling on the ground through developing countries as I did constantly when I had been given the privilege of working on HIV for the UN, that’s all they talk about,” he added. “They are not interested in what goes on at the Security Council, even though that may imperil the world. What they are interested in is what the agencies are doing on the ground to help their people and to work in concert with community-based organizations in those countries.”

Lewis also spoke of efforts to reform the United Nations to make it more functional and less subject to the political calculus underpinning international affairs, but said meaningful reform is tough to achieve given the veto power of the Security Council’s five permanent members (China, Russia, the U.S., the UK and France).

A question-and-answer period following Lewis’s talk drew audience questions on everything from if the UN should be replaced (it’s “worth saving”) to how to measure success when even good leaders can’t achieve much change there (“you judge success by occasional progress”).

In the end, he said during his talk, it’s all about leadership.

“That’s what’s needed,” he said. “People who, in a principled and compassionate way, want to change the world and save the United Nations in the process.”

Lewis is the board chair of the Stephen Lewis Foundation, a non-governmental group that assists AIDS- and HIV-related projects in Africa. He is also co-founder and co-director of AIDS-Free World in the United States.