Researchers at Dalhousie University have found that frailty, more so than amyloid plaques and tangles in the brain, is a key risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

PhD candidate Lindsay Wallace, lead author, and her supervisor Dr. Kenneth Rockwood, are optimistic their findings will be influential, as they were published this week in Lancet Neurology — one of the highest-impact journals in the field.

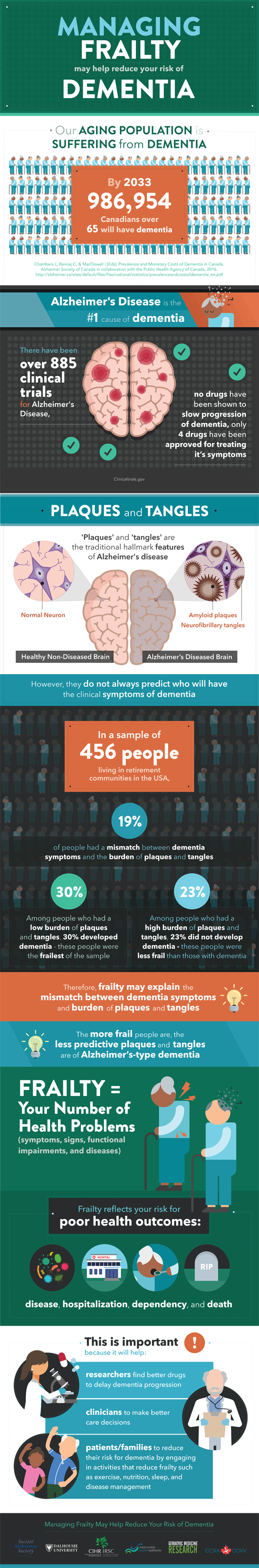

This study is the first to examine amyloid plaques and tangles in post-mortem brain tissues, in relation to both the subjects’ frailty index and the severity of their dementia symptoms when they were alive. The frailty index is a score of relative frailty based on the accumulation of deficits in physical health and ability to function.

“We confirmed that there are a lot of people with lots of plaques and tangles who don’t have dementia,” says Wallace. “These people were less frail. Conversely, there were people with very few plaques and tangles who had severe dementia. These people were very frail… in fact, they were more frail even than the people who had lots of plaques and tangles and dementia.”

Wallace and Dr. Rockwood were joined in the research by Drs. Olga Theou, Judith Godin and Melissa Andrew of Dalhousie and Dr. David Bennett of Rush University in Chicago.

Frailty’s role

Wallace — who is in year four of a five-year interdisciplinary PhD — is a member of Dalhousie’s Public Scholars Program. Public Scholars actively engage in community outreach by giving talks in non-academic settings, sharing their ideas through social media and writing for mainstream publications. They also actively engage with the media by providing expertise and opinions to raise awareness of issues that matter and that help the public make sense of current events.

Wallace analyzed autopsy and clinical data from 456 subjects in Rush University’s Memory and Aging Project, a long-term cohort study of people in a retirement community. She and Dr. Rockwood applied the frailty index (created by Dr. Rockwood and colleagues at Dalhousie) to the cohort to complete their analysis.

Their results suggest that frailty aggravates the neuropathological effects of plaques and tangles — jumbled strands of proteins that accumulate in some people’s brains — and may even be an independent risk factor with nothing to do with plaques and tangles.

At the same time, resilience may be the most important protective factor against Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

“We hope this paper will help shift the focus in Alzheimer’s research from single proteins to much broader issues,” says Dr. Rockwood, Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation’s Kathryn Allen Weldon Professor of Alzheimer Research, professor of geriatric medicine at Dalhousie Medical School, and staff geriatrician at the QEII Health Sciences Centre. “The drugs targeting plaques and tangles have not worked to date. Targeting frailty — rather than waiting for a magic bullet — will have by far the greater impact.”

Identifying new opportunities

In Dr. Rockwood’s view, health researchers and decision-makers should be identifying pivotal opportunities for preventing frailty and dementia, and taking action to do just that. He sees delirium is a key target.

“Delirium is a global change in attention, memory and thinking that occurs quickly, and accompanies acute illnesses such as pneumonia or heart failure, especially in people who are frail,” explains Dr. Rockwood. “Typically it resolves, but it can persist to merge into dementia… again, especially in people who are frail.”

Delirium often goes unrecognized and untreated. This is why Dr. Rockwood insists researchers and providers need to look more closely at what’s being done now and design interventions that screen for risk and target frailty to prevent delirium and downstream cognitive decline and/or dementia.

Seniors’ housing facilities offer another key opportunity to promote the behaviors that are useful in preventing frailty and therefore dementia—such as social interaction, physical activity and healthy eating.

“My interest is in finding ways we can control the burden of dementia now,” says Wallace, who worked as a research assistant with Dr. Rockwood for two years after receiving her undergrad in psychology from Dalhousie. She went on to complete a masters in neuroimaging at McGill University, before returning to Halifax to pursue doctoral studies with Dr. Rockwood. She plans to probe the Rush study’s data further in the final year of her PhD, to gain a greater understanding of how frailty relates to the development of dementia symptoms over time.