President Richard Florizone joined the Dal community as its 11th president and vice-chancellor in 2013. It’s been an eventful five-and-a-half years for the university: big awards, major research announcements, national profile and growing international reach — all culminating in celebrations to mark Dal’s 200th anniversary.

With Dr. Florizone set to leave Dal at year’s end to take on a new role leading the Quantum Valley Ideas Lab in Waterloo, Ont., he sat down for an in-depth chat with Dal News on his time as president. In part one, we discuss first impressions and Dr. Florizone’s 100 Days of Listening project, as well as some of his core priorities and accomplishments as president. (Link to part two.)

Becoming president…

Not everyone who serves as a university president has as extensive a background outside the academy as you have. Given your varied experiences, what did you find that’s unique about being “university president”?

My immediate reaction is that it’s not so much being a university president that’s unique — it’s being president of Dalhousie that’s a singular experience. Canada is a great country, and Dalhousie is the leading research university for four of the great provinces in Canada. And in an age of knowledge, those research universities are more important than ever.

For one, they are responsible for educating professionals to serve this region — everything from physicians and lawyers to poets and journalists. That’s a crucial role in terms of serving society. But it’s also that our society and our economy, more and more, is driven by knowledge, and that the biggest opportunities and challenges we face are too big for any one discipline, sector or institution to tackle alone. Society is relying on universities for that new knowledge, new interpretation, new invention and new partnership to address some of our biggest problems. So being Dalhousie’s president is a singular role at a singular institution.

You arrived at Dalhousie in 2013 with an initiative you called the 100 Days of Listening. It ended up being the start of a robust institutional planning process — but it also gave you a speedy introduction to this university and its people. What did you learn about Dalhousie, and being its president, from those 100 Days?

First off, I’d say the 100 Days experience ended up being even more valuable than I thought at the time. It came out of my own experience and background: my belief that strategy is both a top-down and bottom-up affair. It’s bottom-up in that you need not only the facts and the data, but the hopes, dreams, aspirations of an institution’s people. Then the top-down piece is, how do you actually take that and craft a coherent narrative or strategy that’s going to work? And, of course, being a collegial institution, the next step is getting Senate and Board approval on that direction, providing you with a mandate that is critically important in terms of galvanizing and organizing a path forward.

In terms of what I learned about Dalhousie, it was a lot of things that have shown up in our work over the past five-and-a-half years: the four “Rs,” as I’ve called them, of “retention, research, returns to society and respect”; our priority research areas; and this interesting aspect of our history, this founding vision of being open to all, regardless of class or religious belief. Although I knew that was a vision grounded in the 19th century and those realities and biases of the time, it resonated with me. Sometimes the best kind of directions for an institution are grounded not just in the facts and data and aspirations of its people, but in history, ideas that represent a logical evolution of the institution. So when you can find threads in an institution’s history you can revisit, like a living tree, that’s where you have real power and resonance to find positive ways forward. (Pictured: President Florizone during the 100 Days of Listening.)

In terms of what I learned about Dalhousie, it was a lot of things that have shown up in our work over the past five-and-a-half years: the four “Rs,” as I’ve called them, of “retention, research, returns to society and respect”; our priority research areas; and this interesting aspect of our history, this founding vision of being open to all, regardless of class or religious belief. Although I knew that was a vision grounded in the 19th century and those realities and biases of the time, it resonated with me. Sometimes the best kind of directions for an institution are grounded not just in the facts and data and aspirations of its people, but in history, ideas that represent a logical evolution of the institution. So when you can find threads in an institution’s history you can revisit, like a living tree, that’s where you have real power and resonance to find positive ways forward. (Pictured: President Florizone during the 100 Days of Listening.)

What’s something that people who haven’t been a university president might not appreciate about the role? Or something that might surprise them?

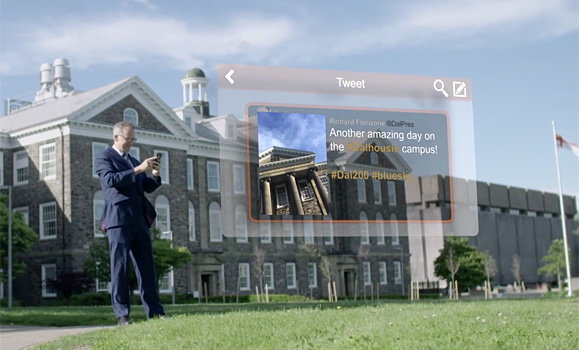

What’s great about the role — and challenging, too — is that involves everything from literally what’s happening in the dining hall to dealing with heads of state. Even when you’re a vice-president, you don’t really have the full sense of what it entails. Because of that, it can seem a bit mysterious to people, which is the principal reason I’ve been on social media: if I can give people a glimpse of what I’m dealing with in the institution, or what I’m up to as president, it might help them feel more engaged and bring a bit more transparency to the role.

It’s been great to meet people in person and, because they followed me on Twitter or maybe we’d had an exchange on there, it was like I was meeting them for the second or third time rather than the first. It meant those first conversations were deeper and richer, a little more informal. That’s one of the real positives: it’s a facilitator. The downside, of course, is that it’s always on — which is true of other elements of the job as well. It’s another channel that can make it harder to turn off at night when you need to.

President Florizone tweets in a still from the Dal 200 promotional video.

The challenge for leaders is finding that balance between openness and engagement, which is critical, and that time when you can stop, digest, plan and strategize — or even to stop and breathe. I often say the bedrock of any leadership position in anyone’s career is to remember food, sleep and exercise. You have to carve out that time not just to be thoughtful and reflective, but to support yourself as a human being.

Priorities and progress…

As you noted, you’ve often framed your priorities as being “the four ‘Rs’”: retention, research, returns to society, and respect. “Retention” is priority one in Dal’s Strategic Direction, too — why has it been such a key focus for you?

I’m really passionate about the mission of universities: teaching and learning, research, and service. And of those, first and foremost we’re an educational institution. To put it really simply, the most important part of the student experience at Dalhousie is getting a degree. Now, there’s a lot of caveats I can add to that, of course, and I don’t want to minimize all the other aspects of education that are so vital. But it’s true that when students come here, and when their parents and family often support them to come here, it’s because they want to get a degree.

So, for me, when I looked at the data, and I saw Dalhousie students weren’t performing as well in continuing in their studies from first to second year as others in the U15 [group of Canada’s research universities], it was a concern, but one that we could mobilize people around solving: it’s so fundamental to our mission and our values. Students and their families are investing their hopes, dreams and aspirations with us —are we supporting them in the way they’re being supported at other institutions? And do we actually know what the barriers are and how to address them?

We’ve been able to make progress on retention, and we’ve done so with initiatives like On Track that have not only been successful, but have really resonated with donors. We’ve been able to go to graduates and alumni and say, “help our student be as successful as you were.” It’s an inspiring message.

How do you think the student learning experience at Dalhousie is changing? I’m thinking, in particular, about the rising emphasis on co-op, work-integrated and experiential learning — it seems to be a major theme in higher education more generally, and something coming up more and more on campus.

It’s coming up across the country, actually, working with Universities Canada and with lots of Canada’s CEOs from the higher ed roundtable.

Here’s why: the future of work and learning is uncertain, and I want to be really clear on that. Anyone who thinks they know what the future holds, what skills are needed, is a little bit wrong. You only have to look back in history to see how education, or the workforce, has changed in ways people couldn’t have predicted. But if you look amidst that uncertainty, there’s a great argument to be made that, with the rise of machines, it’s the skills that make us most human that will be most valuable. That’s not to say the technical skills aren’t important: I’m an engineer, a scientist myself. But it will absolutely be a blend of human and technical skills. (Pictured: President Florizone takes a selfie with Loran Scholar students.)

Here’s why: the future of work and learning is uncertain, and I want to be really clear on that. Anyone who thinks they know what the future holds, what skills are needed, is a little bit wrong. You only have to look back in history to see how education, or the workforce, has changed in ways people couldn’t have predicted. But if you look amidst that uncertainty, there’s a great argument to be made that, with the rise of machines, it’s the skills that make us most human that will be most valuable. That’s not to say the technical skills aren’t important: I’m an engineer, a scientist myself. But it will absolutely be a blend of human and technical skills. (Pictured: President Florizone takes a selfie with Loran Scholar students.)

Experiential learning seems like a perfect way to deal with that uncertainty. Students get to go out and apply their knowledge, and experience a future profession. It’s a testing ground for them. It’s a huge benefit to employers, too. Even if we have to push them, sometimes, to make these positions for students, they know in the long term that it’s one of the most effective ways to trial employees and bring them into their organizations. It’s a real win-win.

But the other thing, which has been talked about much less, is how it’s a feedback loop between the employment system and the education system. Everyone’s talking about how universities should reshape themselves for the future. That’s a good debate, and it should happen. But to come back to my first point: nobody really knows what the future holds. So, what do you need to do? You need to build more feedback loops. Think of a system change instead of trying to predict a certain scenario. If you build that feedback loop, if students go out and do a practicum, it shapes the kind of questions they ask in the classroom, which in turn shapes the professor’s approach and the curriculum. It’s a living dialogue. By having students have that practical experience, you’re creating a feedback loop which helps make the education system richer and strengthens the university.

One of Dal’s biggest achievements during your time as president has been the Ocean Frontier Institute — launching a $220-million global ocean research initiative with the largest federal funding grant in the university’s history. What can Dal learn from that success as it works to advance research and innovation into its third century?

By definition, we’re Atlantic Canada’s research university, and that means we must have a strong, robust agenda for research and scholarship. A strong research strategy is like a table top: you have some supporting legs — priority areas that are a bit higher profile where you attract scale and major resources — but you also need a strong table top, which means strong performance across all academic disciplines. So that’s why we’ve been focused on identifying those core research areas, building them up, and using that as a way to attract resources to also strengthen the tabletop. I think we’ve shown we’ve been able to do that.

President Florizone at the Ocean Frontier Institute announcement with vice-presidents of research for Memorial (Richard Marceau) and UPEI (Robert Gilmour).

With regards to oceans, I think there are three lessons. One is to be confident and think big. When I came here there were some people who said to me, when I said I was asking about large-scale projects, they said, “Oh, you’re from out west, you think big.” And I was really taken aback because, my goodness, we’re Dalhousie, the most important research university in Atlantic Canada. If we don’t think big, who will? We have to be confident in who we are and what we can achieve. I’m glad people are celebrating OFI, but they shouldn’t be surprised that the potential for such a project was right here in our region.

Two, it’s this combination of local strength and global ambition. That’s what OFI is about: how we take what’s locally important and connect it with global standards and global partners. There are other areas we can do that, too, like health, or clean energy, or governance, society and culture — that combination of local relevance and global excellence.

And the third is the power of partnership. Universities have a tremendous power as a convener and a catalyst. If we just conceive narrowly of “what does Dal need?” it leads you to a smaller solution. But by thinking about others, and how we can come together around our core mission, we strengthen ourselves as well.

From the very beginning of your presidency, you’ve talked about Dalhousie’s mission as having three pillars: teaching and learning, research and service. It seems clear that, to you, that third pillar is more than just a byproduct of the first two — that service is an integral part of what we do as a university. What have you learned about the service role a university like Dalhousie plays in our province, our region, our country? And is that role changing as the 21st century progresses?

I don’t actually believe great universities have ever truly been “ivory towers” — I’m not sure that reality ever existed. They always existed to engage: not just to think independently, but to serve society. I think the service mission is important in its own right, but also what it does for teaching and research, and there’s no question that role is growing.

I’d probably tie it back to a few things. One is the knowledge age: our society and our economy are more complex, relying on a population that’s more educated, that needs more knowledge to assess things and develop ideas than it would have needed a century ago. And the issues are such that it requires collaboration across disciplines. We need that rich partnership to solve major issues. And then I think there’s probably some other negative tensions as well — that there’s less trust in institutions. And that means both that the university can be less trusted in some cases, but also it ends up being more called upon: there’s more need for third-party expertise, for other voices and perspectives.

As was the case under your predecessor, Tom Traves, Dal’s physical campus has continued to grow, evolve and change during your presidency. I’m struck, though, by how many projects in the past few years — like the IDEA Project transformation of Sexton Campus, or the forthcoming expansion of the Dalhousie Arts Centre — have been made funded by a wide variety of partnerships: governments, donors, industry, students and more, all stepping up to support them. What does that say, to you, about how universities like Dalhousie get big projects done in this day and age?

Two reasons: one is resources and the other is engagement.

I’m a former VP Finance, and we live in an environment where we know our provincial operating funding is rising at a rate lower than inflation. We have to spend those precious operating dollars very carefully. A big source of pride for me is how projects like the IDEA Project or the new Performing Arts Centre expansion have had such strong external funding, because it preserves are internal operating funds for teaching and other important uses.

President Florizone helps reveal the cornerstone to the new Emera IDEA Building with of the Treasury Board Scott Brison, Premier Stephen McNeil, Architecture student Katie Kirkpatrick and Engineering student Sierra Sparks.

But these partnerships do more than just bring money. The easiest example I can think of is with Emera, where we were initially looking at a purely financial discussion around the IDEA Project, starting at $1 million, and Chris [Huskilson, then Emera CEO] said, “You need to think bigger” — not just in terms of dollars, but what this project could be. And that led to a project that not only met our critical accreditation issues — in terms of lecture space and research space — but incorporated this idea of entrepreneurship space that is great for our students, great for our mission and improves the engagement of the institution and meets some broader public goals, as outlined in the Ivany Report.

In part two of our chat, Dr. Florizone discusses working through some of the major challenges of his time in office and reflects on what he’ll miss about the job and the lessons he takes from his presidency.