This article was originally published on The Conversation, which features includes relevant and informed articles, written by researchers and academics in their areas of expertise and edited by experienced journalists.

Robert France is Associate Professor of Environmental Science and Landscape Studies at Dalhousie University's Faculty of Agricuture.

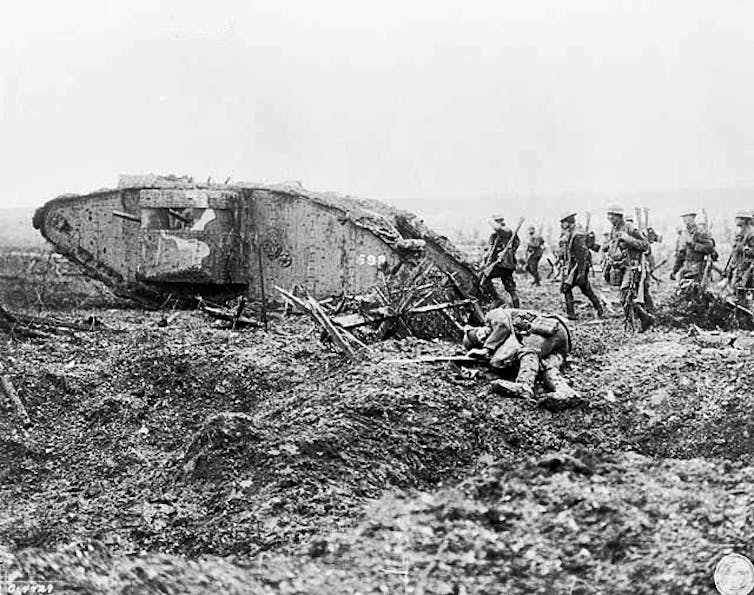

With the armistice signing on Nov. 11, 1918, it was all over: one of the greatest conflagrations the world had seen, the butcher’s bill, in the end, totalling 6,000 soldiers per day for four of the longest years ever experienced. A century on, over the past four summers, I undertook a pilgrimage walk along the complete length of the Western Front from the Swiss border to the English Channel, to bear witness to this inconceivable loss. It was a distance of more than nine hundred kilometres, with side trips ranging over the major killing fields and eastward to the location of the first and the last battles at Mons.

Throughout, I was conscious, often to the brink of heart-rendered grief, of the overwhelming death count. Traversing the landscape slowly on foot rather than by motorized travel enables one to develop a private and profound intimacy with both the terrain and what it reveals, as well as the way in which memory is invoked.

Heaps of bones

The first year’s walk ended in Verdun, a place which set the template in terms of pointless wastage for that which was to come. Here, the Germans hurled everything they had, and the French adopted their “They Shall Not Pass” motto, the result being more than 700,000 dead on both sides. The remains of many these victims are visible today as vast heaps of bones glimpsed through the observation windows at the massive ossuary there.

When standing in front of the Thiepval Memorial or the Menin Gate, many find it hard to wrap their heads around the tens of thousands of names inscribed of those who are “missing,” having no known graves. It may be easier to comprehend this immensity when one can witness a sign of the individuality of loss. This happened to me when crossing a field at the Somme, and coming upon a human jaw bone emerging from the recently plowed spring soil.

There was nothing to do. Out of respect, I took no photo. I unshouldered my backpack and dropped to the ground and shared some moments with the individual before I gently pushed his bones back into the receiving embrace of the earth.

“Sacrificed to the fallacy that war can end war.”

As impressive as the major national memorials are – nowhere more so perhaps than the giant twin-pronged tuning fork of that of Canadians at Vimy Ridge – it is the small, makeshift and private ones, occurring along lonely rural roads, that most resonate the feeling of loss. As fine as is the justifiably famous “Brooding Solider” memorial to Canadians exposed to the first use of poison gas at St. Julien, I was affected more by a small, private memorial nearby.

There, a British family had included a photograph of their relative killed, along with a description of what had transpired. He had lain severely injured in the field immediately in front of where I was standing for a remarkable six days before being recovered and evacuated to a hospital behind the lines, where he soon expired. Lying there unmoving, all alone, among his dead companions for that period, with no water and no doubt in constant pain is unbearable to contemplate.

Of all the tens of thousands of graves seen, it is worth explicitly mentioning those of three individuals.

The last cemetery I visited lay outside of Mons, in Belgium. Here, separated by a distance of about thirty metres, lie the graves of John Parr, the first British Commonwealth soldier killed on Aug. 21, 1914, and of Canadian George Price, the last, killed at 10:58 am on Nov. 11, 1918, tragically just two minutes before hostilities ceased.

They are separated in time by the deaths of 953,000 of their compatriots. A gruesome math exercise reveals the true magnitude of that horrific statistic: if you stacked up all those bodies between the two gravesites, the wall of corpses would tower almost 32 kilometres high. It is unfathomable.

That is only the toll for the British Commonwealth; both France and Germany lost more men. And then there are those from all the other nations.

One grave, above all others, stands out in sharp contrast. Its inscription is remarkably different from the oft-quoted “for King and Country” slogan. It is located near Ypres and is for Arthur Young. Written by his father — tellingly a diplomat — it is a bitter indictment to the purposeless waste of a generation, and reads:

“Sacrificed to the fallacy that war can end war.”

There is no better testament to sum up the whole enterprise. And there is, of course, nothing that is ultimately more depressing.

The war did not end all wars

The absolute saddest thing I observed during my entire pilgrimage was the series of red and white banners hung at the exit from the war museum in Ypres. On them are listed, one after another, all the wars that have transpired in the years since ‘The War to End All Wars’ finished in 1918. Each name leaps out as a stark and shameful reminder of our collective failure.

I counted 101 armed conflicts throughout my six decades of life; and to my embarrassment, there were names on that banner of armed conflicts about which I had never head. Worst of all, however, was that the last panel contained space…waiting to be written on in the future.

Remembrance is essential, but it is not enough. More than a tenth of a million people have lost their lives due to armed conflict in 2018.

When we remember the end of the Great War on this Nov. 11 and subsequent remembrance days and think of Ypres, we must reflect upon Yemen; when we mourn the dead at the Somme, we must rue the deceased in Syria. And somehow we need to shift from contemplation to action.

While the rise of right-wing populism in the West is meritoriously troubling, in the end, both America and most of the rest of us will survive another two or six years of U.S. President Donald Trump. Most, but not all. For the same cannot be said for the hundreds of thousands whom will die in wars distant from North America and Europe which receive correspondingly little or even no media coverage over that same time.![]()

Read the original article on The Conversation.

Dalhousie University is a founding partner of The Conversation Canada, a new-to-Canada online media outlet providing independent, high-quality explanatory journalism. Originally established in Australia in 2011, it has had more than 85 commissioning editors and 30,000-plus academics register as contributors. A full list of articles written by Dalhousie academics can be found on the Conversation Canada website.