It could be considered the global CSI for high seas fisheries.

In two new groundbreaking studies, researchers from Dalhousie University, Global Fishing Watch and SkyTruth have applied cutting-edge technology to map exactly where fishing boats may be transferring their catch to cargo vessels at sea.

This practice, known as transshipment, increases the efficiency of fishing by eliminating trips back to port for fishing vessels. However, as it often occurs out of sight and over the horizon, it creates major challenges, including enabling illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

“Because catches from different boats are mixed up during transshipment, we often have no idea what was caught legally and what wasn’t,” says Kristina Boerder, a PhD student in Dal’s Department of Biology and lead author on the Science Advances paper, published this week.

The trials of transshipment

Transshipment can also facilitate human rights abuses and has been implicated in other crimes such as weapons and drug trafficking. It often occurs in the high seas, beyond the reach of any nation’s jurisdiction, and where policy-makers and enforcement agencies may be slow to act against an issue they cannot see. By applying machine learning techniques to vessel tracking data, researchers are bringing unprecedented transparency to the practice.

“So far, this practice was out of sight out of mind, but now that we can track it using satellites, we can begin to know where our fish truly comes from,” says Boris Worm, a Marine Biology professor in Dal’s Faculty of Science and co-author of the Science Advances paper.

By using the same sophisticated machine learning technology and satellite identification systems originally developed to map the global footprint of fishing from space, researchers at SkyTruth and Global Fishing Watch were able to track the behaviour of refrigerated cargo vessels (reefers); determine when and where transshipment occurs; and which fleets are most involved in this practice. These basic findings and the associated dataset were published this week in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Unprecedented studies

Researchers at Dalhousie University, collaborating with SkyTruth, built upon this work to identify for the first time the fishing vessel types and fisheries most involved in transshipment, as well as what proportion of high seas catch is transshipped versus landed directly. They also traced seafood supply chains for tuna fisheries in the Indo-Pacific. Together these publications provide the most complete, global view of transshipment to date and demonstrate what is possible through interdisciplinary collaboration.

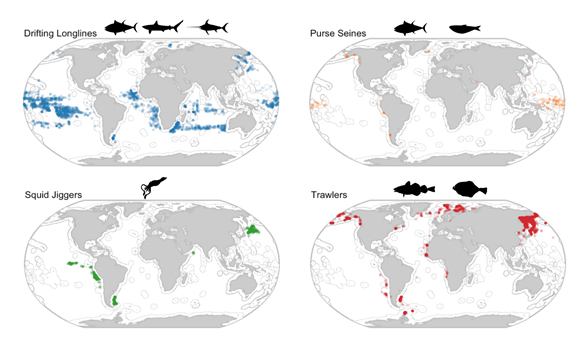

Global patterns of transshipment for different fishing gears. Shown are all likely encounters (colored dots) between reefers and fishing vessels as identified from AIS data spanning 2012 to 2017 and separated by fishing gear type. Exclusive Economic Zones are outlined in light grey, pictograms illustrate major target species. Boerder, Kristina, Miller, Nathan A., Worm, Boris (2018) Global Hot Spots of Transshipment of Fish Catch at Sea.

“These unprecedented studies serve as examples for how big data experts, NGOs and academics can come together to address critical, global challenges that were up to now too large, too complicated, or simply too hard to observe,” says Nate Miller, a data scientist at SkyTruth and author on both papers.

Between 2012 and the end of 2017, the Dalhousie team observed 501 reefers meeting with 1856 fishing vessels in 10,510 likely transshipment events worldwide, with trawlers (53%) and longliners (21%) involved in the majority of cases. They discovered that although transshipment is occurring in all oceans and across 42 Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), it is more common in distinct hot spot areas, including off West Africa, Russia and in the tropical Pacific.

“I think this really touches everyone who eats fish, and at a time when people are more concerned about where their food comes from, this knowledge will be really helpful,” says Kristina Boerder. “A better understanding of what happens to seafood before it reaches our plates will hopefully help consumers buy legally and sustainably caught fish without a ‘fishy’ past.”

A new age of fisheries management

The research also highlights novel ways to trace seafood supply chains and identifies priority areas for improved trade regulation and fisheries management at the global scale. The studies mark the first step towards better visibility into the often shadowy practice of transshipment. An improved understanding of transshipment can help governments, NGOs and academia to support both regional and global efforts to strengthen monitoring and enforcement to eliminate illegal fishing.

“I believe we are entering a new age of fisheries management, where for the first time in our history we can truly see what goes on beyond our shores,” says Dr. Worm.

Read:

“Identifying global patterns of transshipment behaviour”

“Global hot spots of transshipment of fish catch at sea”