Editor's note: This article was originally published in May 2018. It has been re-published and updated with the news that Jeremy Dutcher is the 2018 winner of Canada's prestigious Polaris Music Prize.

The first voice you hear on Jeremy Dutcher’s remarkable new album Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa is his own, a rich and powerful tenor singing in his native Wolastoqey language over a solitary piano.

But by the time the opening track (titled “Mehcinut”) reaches its massive orchestral peak, another voice begins to sing its refrain: crackled, unadorned, like an echo pulled from the ether of history. That voice, recorded over 110 years ago, is that of a Wolastoqiyik man named Jim Paul, who sings a traditional melody before describing his perspective on death and what comes after. Collected by anthropologist William H. Mechling, the recording has been stored on wax cylinder in the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec for decades.

“It’s some of the earliest sound-capturing technology, used to collect the songs of my ancestors,” says Dutcher, a member of the Tobique First Nation in New Brunswick.

It was one of his community’s elders, Maggie Paul, who tipped him off about the collection when he was pursuing research as part of his dual BA in Music and Social Anthropology from Dalhousie. (Dutcher graduated in 2012.) He struggles to find words to describe how powerful it was to hear the recordings for the first time, saying the experience made him feel “almost outside the realm of time.” And it inspired the project that’s making Dutcher a very big deal in the music world.

Connecting past and present

Released in April 2018, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa (which, translated, means Our Maliseet Songs) is an album sung entirely in Wolastoqey, the language of the Wolastoqiyik whose traditional lands lay alongside the Saint John River in New Brunswick. (European settlers long referred to the Wolastoqiyik as the Maliseet.)

The Wolastoqey language is endangered; there may be fewer than 100 fluent speakers still alive. But though the words of Dutcher’s songs may be inscrutable to most listeners, his music’s power transcends language. The album has been featured in outlets such as Billboard, CBC Music, Noisey, Exclaim and The Coast, quickly becoming one of the most acclaimed records in Canada this year.

And in September 2018, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa received Canada's most prestigious music award: the Polaris Music Prize. Voted on by more than 200 music writers, editors and broadcasters, with the final decision made by a grand jury, the award honours the best Canadian album of the year without regard to genre, sales or label affiliation.

“The reception [to the record] has been really beautiful, to be honest; lots of people reaching out from home and giving their congratulations,” says Dutcher, who now resides in Toronto. “I always believe that if you put something out with beauty and with love, that it will come back to you in that way. That’s sort of what this experience has shown me.”

Each of the album’s 11 songs is based on one of the traditional melodies found in Mechling’s recordings. Dutcher incorporates those recordings as samples, but explodes them, orchestrally, in thrilling new directions. At times bombastic in its power, at others peaceful and reflective, the record feels like a soul-stirring conversation between musical traditions: classical, Indigenous, folk songwriting, orchestral post-rock and so many others. And by using voices from more than a century ago alongside Dutcher’s own singing, the record almost uncannily seems to flatten time itself.

“That connection between past and present was important to me, but also thinking about the future,” says Dutcher. “I spent a lot of time thinking about our language and our linguistics and how that affects our worldview.

“That connection between past and present was important to me, but also thinking about the future,” says Dutcher. “I spent a lot of time thinking about our language and our linguistics and how that affects our worldview.

“In Wolastoqey, our language, we don’t really have past tense or future tense. It’s all part of experience. With music, you can play with time in so many ways, quite literally through a time signature, or by bringing in old voices and other ways too... I really wanted to represent that in what I was putting forward as an artistic proposal.”

A journey from scholarship to songwriting

The dual spirit of musical creation and cultural anthropology that inspired Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa can be traced back through Dutcher’s time at Dalhousie. He began his studies focused solely on music, quickly impressing with his skill as a vocalist and willingness to learn technique.

“He’s a very special performer,” says Marcia Swanston, professor of voice in the Fountain School of Performing Arts, who worked closely with Dutcher over five years.

“He has a deep connection to the text and the music. Sometimes singers are focused on a beautiful sound, but he also informs his singing with a deep connection to the dramatic meaning of the words, making him a great communicator… he’s translated his classical voice studies into something exciting and unique to which we all relate.”

Branching out at Dal into courses in the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Dutcher embarked on an honours project bridging his two scholarly worlds, exploring the tonal differences between western classical music and traditional Wolastoqiyik music.

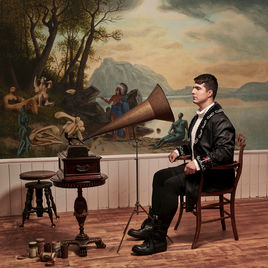

(The Stoodio photo)

“I was cataloging all these songs and their tonalities, trying to find similarities between these two systems and also where they didn’t fit together. That led me onto doing a massive scan of all the Wolastoqiyik songs out there in our communities — some stuff that I knew growing up, for sure, but I learned a lot more and got to interview some incredible musical leaders in our community, like Maggie Paul.”

Paul is a “song carrier,” who has spent much of her life trying to resurrect and sustain Wolastoqiyik musical traditions. Dutcher includes a recording of one of his interviews with her on the song “Eqpahak,” named after an island in the Saint John River.

“When I was interviewing her,” recalls Dutcher, “she talked about how when she was growing up there was no traditional music. It had gone so far underground. Up until the fifties, our cultural practice was illegal in this country. We weren’t able to gather and do ceremony in public or sing our songs in public or dance. She grew up in that era of deep repression and shame around who you are.

“Through her work — bringing these songs back, and the research she did — it has allowed me to do that work as well, and carry on what she started.”

Taking inspiration on tour

In December 2017, Dutcher performed as part of New Constellations, a “nation(s)wide tour” combining Indigenous and non-Indigenous performers featuring headliners like Stars, A Tribe Called Red and fellow Polaris Prize winners Lido Pimienta and Feist in various cities.

“The diversity of voices that were brought together was really incredible,” says Dutcher. “To be on a tour bus with some of those people was so eye-opening and perspective-shifting. To do it as a young artist, when I’d never really toured at all, it was cool to be in that space and try and absorb all of the lessons everyone had to offer.”

Dutcher’s performance at the Halifax New Constellations show was stirring, even with just him, his piano and the audio samples from the archival recordings. With additional band members in tow now, he’ll have an even larger musical canvas to bring these traditional melodies to new audiences.

“It’s helped me better understand my place in a continuum of Wolastoqiyik, our people,” he says about making the album. “Even through all of the things that have happened in our country to oppress or repress our culture and language, we’re still here.”