This article was originally published on The Conversation, which features includes relevant and informed articles, written by researchers and academics in their areas of expertise and edited by experienced journalists.

Author Shirley Tillotson is a retired professor of Canadian History at Dalhousie and Inglis Professor of the University of King's College.

If your income is mainly a paycheque, filing a Canadian income tax return these days is pretty easy. And that’s no accident.

Smart innovations in tax administration in the 1950s built a slick collection system that worked. Except, of course, for small business. And, for the moment, let’s not speak of the many avenues of escape that capital income has enjoyed.

But taxing employees? We figured out how to do that pretty painlessly almost 70 years ago. Surely we can do the same for more tax filers today.

When federal taxation of wages and small salaries was launched during the Second World War, there was incomprehension, chaos and widespread resentment. Tax protest was part of several strikes by organized labour in 1941 and 1942. Non-union workers refused overtime for tax reasons, a real problem for wartime industries.

The new income tax law left lower-income workers no wiggle room in their household budgets.

My book, Give and Take: The Citizen-Taxpayer and the Rise of Canadian Democracy, contains examples of protest letters that poured in to the federal Finance Department from people like Miss W.E. Drummond. She was a white-collar employee earning a decent wage. She detailed every item in her weekly budget and asked: “What am I to do, drop this Insurance for my old age? Let my home people starve or go on relief?”

Tax forms were nightmarish

To complaints like hers, James Lorimer Ilsley, then the finance minister, responded with concessions such as allowing a tax credit for some insurance premiums.

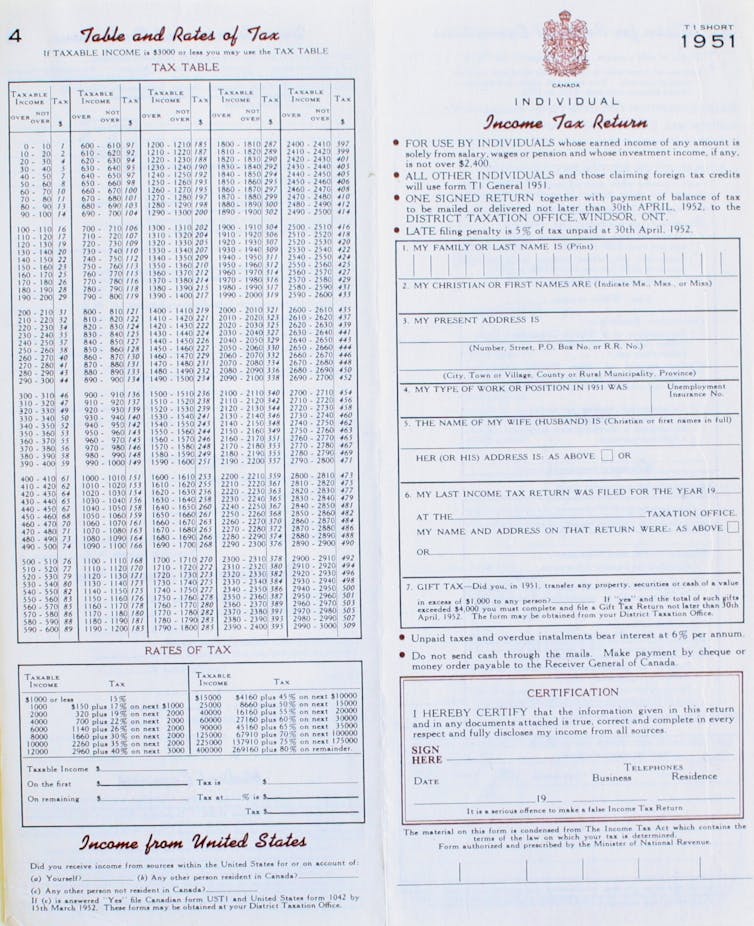

But concessions made another tax problem worse: The forms. Their format was unchanged from the 1920s and 1930s, when federal income taxpayers were mostly professional men or business owners. Expressed in dense legalese, they were typeset mostly in six and seven point. If Miss Drummond wanted to know whether her insurance payments were deductible, she had to wade through 111 words of lawyer-ly instruction, 62 of them in tiny print, the rest of them smaller.

Confronted with these forms, semi-literate fishermen in coastal British Columbia and barely educated millworkers in New Brunswick (or their often equally ill-equipped employers) struggled to understand tax terms like “married status.”

“Married status” would lower their taxes, and unmarried people could claim it. But first they’d have to figure out if they and a “wholly dependent relative” lived in a “self-contained domestic establishment… containing at least two bedrooms in which residence amongst other things the taxpayer as a general rule sleeps and has his meals prepared and served.” And served?!

‘Tax conscious’

Dreadfully inaccessible forms were not the only source of pain for wage-earning taxpayers.

Some people thought that paying income tax was meant to hurt, at least a little.

Former Prime Minister Arthur Meighen made this view clear in the 1939 Senate debate on war income taxation. Exemption levels should be so low that almost every earner would be an income taxpayer. Only if they personally felt a pinch in the pocketbook would voters be “tax conscious.” Only then would they care about “preventing waste in government.”

Meighen’s wish came true. Not only did the wartime government lower exemptions in 1941, and drastically so in 1942, they also told the nation’s payroll clerks to clip from paycheques only 95 per cent of the amount that would likely show up in employees’ year-end calculations of tax payable.

That way, at tax filing time, most employees would still owe income tax, beyond what the payroll clerk had been collecting all year. Pretty much everyone working for a wage would have to actually fork over some cash with their return.

To be fair, this was a way of avoiding any risk of over-deducting. But it also made taxpayers feel the pain of payment — to good moral effect, some thought.

Debts went unpaid

By 1951, however, tax administrators had discovered a downside to this exercise in moral instruction. Every year, hundreds of thousands of small tax liabilities went unpaid. Collecting those debts placed the federal government in the role of big, bad collection agency garnishing some pretty small wages.

The solution: Abandon the practice of payroll clerks collecting throughout the year only 95 per cent of tax owing. Tell them to deduct 100 per cent instead.

No more making tax debtors out of struggling wage earners. Instead, most employee tax returns would produce — yippee! — a refund.

In the spring of 1952, Canadians rushed enthusiastically to file their tax returns (or so it was reported in the Toronto Daily Star).

But the Globe and Mail’s editors took a darker view. The revenue authority was collecting more tax than was owed. The collections were therefore “illegal,” “contrary to the principle underlying our constitution,” and “stupid.”

Why “stupid?” As the editors of the Winnipeg Tribune argued, if taxpayers didn’t actually pay cash at tax time, they might forget that “government was spending a great deal of money.” They’d no longer be tax conscious.

Built revenue for pensions and medicare

For the remainder of the Liberals’ term under Louis St. Laurent, opposition members like Waldo Monteith pushed this point. But the system continued. It built revenue for the welfare state in much the same way that personal savings build when you set up a monthly deduction.

The over-payment method was not the only innovation in tax administration. For the 1948 tax year, a short T1 form was introduced. Pamphlet-sized and legible, it was clearly the work of a skilled designer. Non-lawyers could read it without weeping.

These and other innovations have made reporting income and claiming credits on employment income relatively easy. Perhaps we’re now at the point where many of us — the 57 per cent of filers with income primarily from employment — would be well-served by a more automated tax assessment. The ritual of completing even a simplified form may be just another exercise in tax consciousness, a flogging of the form-phobic that only inflames anti-tax feeling.

For the other 43 per cent, and especially for small businesses where tax compliance competes painfully with other uses of time and money, the lesson of the 1950s is that tax administration matters. As Canada’s auditor general has recently reminded us, when the revenue agency is underfunded, service shrivels.

We have seen the current government increase CRA funding to improve services to small business in particular and taxpayers generally. It’s too soon to tell (from publicly available information, at least) what impact this will have.

But making employees’ tax compliance easy helped make personal income tax the workhorse of Canada’s taxation system. Now we need to do the same for small business.

![]() We should consider simplifying the law, of course. But even if legal complexity is required for fairness, as it often is, skilled administration can make paying taxes much less painful. And that might protect the revenue — as well as serving the taxpayer.

We should consider simplifying the law, of course. But even if legal complexity is required for fairness, as it often is, skilled administration can make paying taxes much less painful. And that might protect the revenue — as well as serving the taxpayer.

Read the original article at The Conversation Canada.

Dalhousie University is a founding partner of The Conversation Canada, a new-to-Canada online media outlet providing independent, high-quality explanatory journalism. Originally established in Australia in 2011, it has had more than 85 commissioning editors and 30,000-plus academics register as contributors. A full list of articles written by Dalhousie academics can be found on the Conversation Canada website.