This article was originally published on The Conversation, which features includes relevant and informed articles, written by researchers and academics in their areas of expertise and edited by experienced journalists.

Sylvain Charlebois is a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University.

Bill Morneau is perhaps an influential figure in Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s cabinet, but he’s not conducting himself like most finance ministers. Given the budget he presented recently, he may be more of a social justice warrior.

Supporting more diversity, equality and inclusiveness is obviously critical to the betterment of our society, but I believe most Canadians expect more from a finance minister. His recent budget was sorely lacking.

There were no plans to balance the books and, most importantly, there were no mitigating strategies presented in relation to a floundering global trade environment.

Few details were given on the government’s plan to deal with NAFTA’s possible demise on Washington’s “America First” policy, and there were no attempts to circumvent trading challenges.

The ugly face of protectionism is slowly making its way across the globe. U.S. President Donald Trump announced last week he’s considering new trade restrictions, including a 25 per cent tariff on imported steel and a 10 per cent duty on aluminum, though Trump’s trade and manufacturing adviser says Canada and Mexico will be exempt — for now, and depending on how NAFTA negotiations go.

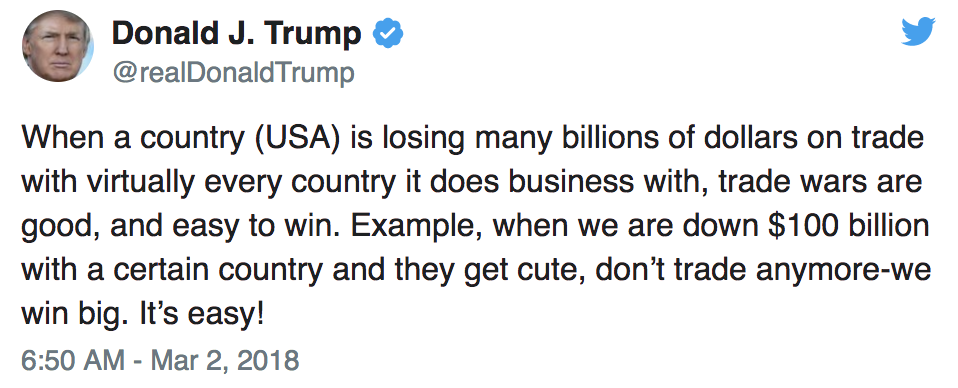

Nonetheless, trade wars are something Trump appears to relish.

Despite recent trade deals signed by Canada, the world seems at odds with open trade, and instead everyone wants to protect their own domestic markets.

This is a seemingly dangerous path given that agriculture and food are often considered the most vulnerable and sensitive sectors when it comes to trade barriers.

They’re easy targets. Tariff or even non-tariff barriers can make a significant dent in a country’s economy almost instantly, and consumers are often affected the most.

Most economists see freer trade among nations as an absolute good until politics come along. But not all trade is created equal. Some win while others lose, and given the economics of our country, Canada cannot win many trade wars, especially not with the United States.

In fact, we are already witnessing how a trade war could affect the Canadian agrifood sector as Canadian pulse farmers are now bracing for some major trading headwinds from India.

Some political opponents are linking our prime minister’s recent globally mocked visit to India with the country’s decision to increase tariffs on chickpeas from 44 per cent to 60 per cent, overnight.

The decision comes after India introduced a variety of tariffs on pulse crops, including lentils, peas and chickpeas, in the past few months.

These are growth sectors for our economy. Canadian pulse exports to India alone are worth well over CDN$1 billion. This could easily escalate further and affect other sectors of our agrifood economy.

In Europe, South America — everywhere — we are seeing more governments reducing their exposure to international markets. It cuts risks and simplifies business for many producers.

But there is also considerable consensus around the world that trade wars can backfire and ultimately hurt consumers.

Expensive way to retain jobs

Trade barriers, which are often scientifically unjustifiable but politically motivated, make economies weaker and less competitive over time. Duties may look like an attractive, simple mechanism to protect domestic interests, but they are an extremely expensive way to retain jobs in an economy.

But Canada doesn’t exactly have an immaculate record either on trade barriers.

Canada itself applies heavy duties on many imports, including dairy products, poultry and eggs. These duties are embedded into our supply management regime, considered by many as one of the most protectionist policies in the world.

In some cases, duties exceed 300 per cent.

Most countries do enact duties on a variety of food products, but Canada goes even further by enabling and controlling domestic production with quotas. We are the only western economy still doing it. That makes it extremely awkward to ask trading partners for exemptions to their own trade barriers.

What remains under-appreciated is how intertwined all economies are, not just those of the U.S. and Canada. Duties in one sector will affect the ability of other sectors to trade. It is difficult, if not impossible, to link steel and aluminum with dairy, poultry and/or eggs, but the connection exists.

Trade wars easily escalate, spelling trouble for an open economy like Canada’s. Given our abundance of resources and knowledge, we have plenty to share. Almost 60 per cent of our economy is trade-driven.

Morneau essentially short-changed Canadian taxpayers last week with his so-called budget. I believe the government’s focus on equality would have been better served at another time.

![]() We should not be shocked to see Ottawa utterly unprepared for Washington’s wrath towards its trading partners. Upholding equity values for our country is undoubtedly noble, but the government could fall short on its social promises if it runs out of cash.

We should not be shocked to see Ottawa utterly unprepared for Washington’s wrath towards its trading partners. Upholding equity values for our country is undoubtedly noble, but the government could fall short on its social promises if it runs out of cash.

Read the original article on The Conversation.

Dalhousie University is a founding partner of The Conversation Canada, a new-to-Canada online media outlet providing independent, high-quality explanatory journalism. Originally established in Australia in 2011, it has had more than 85 commissioning editors and 30,000-plus academics register as contributors. A full list of articles written by Dalhousie academics can be found on the Conversation Canada website.