Like the loveable hero in a children’s cartoon, a striped tropical fish sporting a fluorescent green heart is bound to draw a crowd. While this little specimen is not (yet) attracting the crayons and Lego set, it is the centre of attention among a growing number of medical scientists and specialists worldwide.

We’re talking about the zebrafish, a four- to six-centimetre minnow that has led researchers to remarkable revelations about the development and treatment of human disease. These include a surprising discovery about prostate cancer, and a hopeful one for childhood leukemia, in studies led by Dr. Graham Dellaire and Dr. Jason Berman at Dalhousie.

Transparently accurate model of human disease

To state the obvious, the zebrafish does not seem to share many human qualities. But it’s a vertebrate with two eyes, a mouth, ear, nose, brain, spinal cord, intestine, pancreas, liver, bile ducts, kidney, esophagus, muscle, blood, bone and cartilage. In fact, 70 per cent of human genes are found in zebrafish.

That means when diseases invade those body parts in humans, scientists can try to model the same conditions in zebrafish and manipulate them in search of new treatments. And zebrafish make it so easy to see the results: they are transparent.

“We can take a three-day old embryo and most of the organs have already developed,” explains Dr. Dellaire, a professor in the departments of Pathology and Biochemistry & Molecular Biology who’s been collaborating on zebrafish research for about a decade with Dr. Berman, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at the IWK Health Centre and professor in the departments of Pediatrics and Microbiology & Immunology. “In three days, we can conduct an entire experiment and start to see and measure the impact.”

Dr. Dellaire’s main interest is the treatment of solid tumours found in breast, lung and prostate cancer. He sees zebrafish as an important vehicle for developing personalized cancer therapies. “If we can inject the embryo with cells from a human tumour and then introduce a range of chemotherapy treatments, we can figure out which one works best for a particular patient,” he says.

If we can’t prevent cancer, personalized chemotherapies could be the game-changer we’ve all been waiting for. But, of course, nothing is simple: the tiny transparent zebrafish can also expose problems no one was looking for.

The challenge of prostate cancer

Prostate is the most common cancer and third-leading cause of death in Canadian men. The “Movember” campaign, now in its 10th year in Canada, has tried to reduce that grim statistic by encouraging men to grow a moustache as a symbol of unity (and as a fundraising initiative) in the battle against prostate cancer. Nevertheless, the disease often confounds treatments, especially when the cancer has spread beyond the prostate gland (stage three or four).

Although men with early-stage prostate cancer are cured by surgery and radiation, cures are more elusive for men with late-stage prostate cancer. These men are treated with drugs to curtail testosterone, the androgen hormone that fuels the growth of prostate cancer cells. Within three years of starting treatment, 100 per cent will develop castration-resistant prostate cancer that no longer responds to anti-androgen therapy. Once a patient develops castration resistance, he rarely lives longer than 24 months.

About five years ago, a potent new drug called enzalutamide (brand name Xtandi) entered the market, with heartening promises that it could extend the lifespan of castration-resistant patients for several months. Dr. Dellaire and his team of researchers had no reason to suspect otherwise. They simply wanted to continue their quest to personalize cancer treatments.

“To do that correctly, with faith that the growth and behaviour of the cancer in zebrafish reflects tumour growth in humans, we needed to know that the prostate cancer cells are responding to testosterone and androgen-blocking agents like enzalutamide,” says Dr. Dellaire.

An unexpected side effect

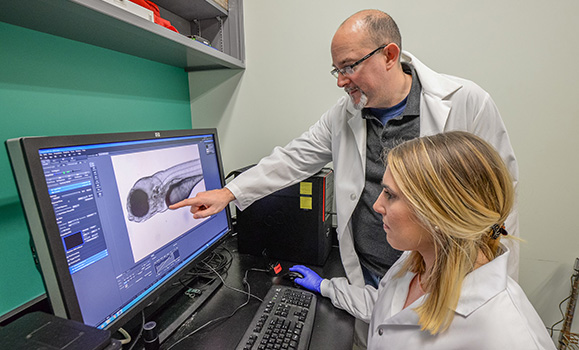

In collaboration with Dr. Berman, the Dellaire group began to study how prostate cancer cells responded to testosterone and enzalutamide after engraftment in zebrafish. Research associate Nicole Melong played a key role in developing the techniques that enabled the researchers to successfully culture prostate cancer cells and graft them into the zebrafish, and in conducting the drug-testing studies that followed.

Nicole Melong and Graham Dellaire examine cancer cells in a zebrafish embryo.

The mighty zebrafish did not let the researchers down — but the testing soon exposed a previously unknown side effect of enzalutamide.

When the drug was added to zebrafish water, the fish developed an erratic heart beat (arrhythmia), which quickly led to bradycardia (a very slow heartbeat). Within three days, all the zebrafish died. Even when researchers adjusted the potency of the drug, they found it caused heart problems at half the concentration found in the blood of patients on enzalutamide.

Not all men are susceptible to heart arrhythmia but, as Dr. Dellaire points out, heart problems are more likely to develop in men over the age of 60 — just the age when prostate cancer rates begin to spike.

“There is no black box warning for physicians about possible cardiac side effects, and no prescribing guidelines in the literature on the company website,” he notes.

What would Dr. Dellaire do, if faced with the difficult choice between an effective cancer treatment and possible cardiac arrest?

“Before taking the drug, I would ask my physician for a stress test to make sure I have no underlying heart condition.”

This study, funded by Prostate Cancer Canada and the Movember Foundation, was published in the online journal Scientific Reports.

Fishing for answers to childhood leukemia

Zebrafish wear no blinkers when it comes to the age of patients they are willing to save. Dr. Dellaire collaborated with Massachusetts General Hospital pathologist, Dr. David Langenau, on a pediatric leukemia study published this fall in Cancer Discovery. Specifically, the researchers wanted to know why T-Cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is more resistant to treatment and more likely to relapse than other, more common childhood leukemias.

This work began at Massachusetts General, where researchers used a zebrafish model of T-ALL to look for genes that made the disease more aggressive. In this model, the leukemia cells glow red under the microscope, allowing the growth of the leukemia to be followed easily in the zebrafish embryos, which can be easily imaged due to their transparency.

The researchers found that a protein called “TOX,” expressed by the TOX gene, impedes DNA repair in leukemia cells, increasing genetic mutations and the aggressiveness of the disease. Children who develop this kind of leukemia are known to express higher-than-average levels of TOX.

“Forty per cent of the zebrafish had leukemia within 100 days. When they added the TOX gene, sixty to seventy per cent developed the disease,” explains Dr. Dellaire.

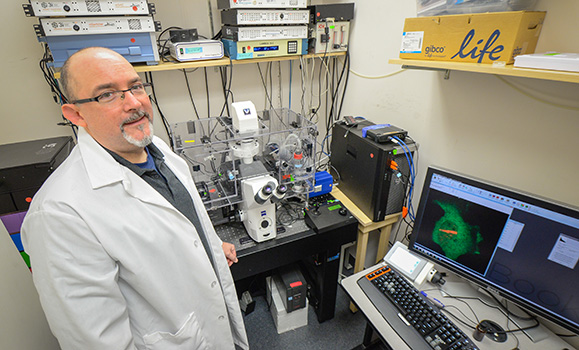

The focus of the investigation then shifted to the Dellaire lab at Dalhousie, where he and his team have been studying DNA repair for more than two decades. Here, the researchers monitored the effect of the TOX gene on pathways that enable — or block — DNA repair in live human cells, using a $600,000 microscope funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation.

They found that TOX could block a common DNA repair pathway that joins broken DNA ends, which explained how this gene could increase mutations in leukemia cells. Now that a link has been established between the TOX gene and impaired DNA repair in T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia, the hope is that scientists can explore customized therapies for children with leukemias that show a high expression of that gene.

The Canada Foundation for Innovation, NSERC and Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation funded the microscope Dr. Dellaire used to study the role of TOX protein in blocking DNA repair in leukemia.

From a little pond to a big sea

Zebrafish first swam into the scientific spotlight in the 1990s in Germany and Boston. Dr. Berman, who learned how to develop zebrafish models of disease at Harvard University, brought them to the forefront in Halifax in 2005. In the beginning, he worked out of a lab with fish facility that could house only 2,000 zebrafish. Today, he and Dr. Dellaire and many other researchers have access to Dalhousie’s state-of-the-art Zebrafish Core Facility, opened in 2014. Dr. Berman oversees this multi-user facility, which can house up to 70,000 zebrafish.

Thanks to their small size, low cost, transparency, and an uncanny ability to model human disease, these little fish are performing well above their weight in gold as potential life-savers.