In the fall of 1914, just weeks after the outbreak of the First World War in Europe, Dalhousie welcomed a new batch of students into its ranks. No one could have foreseen at that early stage just how big a toll the bloody conflict would take in the coming years on all involved. That year’s incoming class was no exception.

The war and its broader impact meant high attrition rates for university students: by the time convocation rolled around roughly four years later, only 20 members of the Class of 1918’s 72 members were still enrolled at the university.

Ernest Parker Duchemin was one of them. In a valedictory address delivered on May 9, 1918, a day before that year’s spring convocation, the Bachelor of Arts grad from Sydney, N.S., spoke of the dark shadow the war — still raging at the time — had cast over his class.

“It has haunted us at our studies as at our sports, in the lecture rooms, at our college functions, and in all the varied activities of college life,” he said in the speech, later reproduced in the Dalhousie Gazette. “The war has interpreted history, literature and philosophy for us in new and impressive ways. It has broken our class circles by the departure of those who have responded to the call of country."

Indeed, 34 of Duchemin’s classmates left Dal during those years to serve overseas on the front lines. Some discontinued their studies to contribute to the war effort in other ways. Three made what he called “the supreme sacrifice,” perishing on the battlefield.

“Just another bunch of college grads”

Not all graduating classes at Dal have been through so much. But members of each class — from those in the first small cohort in 1866 to those in the more than 3,000-strong group graduating this week — have had their own set of defining events, experiences and milestones that have shaped not only their education, but the world they exited into come convocation.

The Class of 1933, for instance, entered Dal in 1929 at the height of an era of unparalleled prosperity. Just weeks later on October 29, the U.S. stock market crashed spectacularly, setting off what was to become the longest, most brutal recession in the history of the Western industrialized world.

The descent into economic depression would come to radically reshape the world into which those students emerged four years later. Opportunities that once seemed so plentiful had long ago dried up, leaving the graduates to ponder the very usefulness of the education they’d worked so hard to achieve.

"Now we go out to face the stern realities of life,” said class valedictorian E. Benjamin Rogers (left, upper-left photo) in a downbeat speech to fellow Class of ’33 graduates that May. “When we were children we used to hear that the world needed college-trained people. But times have changed. Today we are regarded as just another batch of college graduates going out to swell the ranks of the unemployed."

"Now we go out to face the stern realities of life,” said class valedictorian E. Benjamin Rogers (left, upper-left photo) in a downbeat speech to fellow Class of ’33 graduates that May. “When we were children we used to hear that the world needed college-trained people. But times have changed. Today we are regarded as just another batch of college graduates going out to swell the ranks of the unemployed."

Rogers, an Arts grad from Prince Edward Island, lamented the lack of cooperation on the part of world leaders and the rise of nationalism, distrust and greed — all of which he claimed (somewhat presciently) brought about the threat of a new war. The seizure of power in Germany by Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party four months earlier, though not explicitly mentioned, was no doubt on Rogers’s mind.

Faced with such darkness, Rogers envisioned his own classmates as a force for good.

“Today we go out to face a weary, troubled, discouraged world,” he said. “Let us bring to the solution of its problems the spirit of moderation and toleration with which the university has imbued us, the course and the determination which our forefathers met their problems, and the enthusiasm of youth.”

Celebration in a time of loss

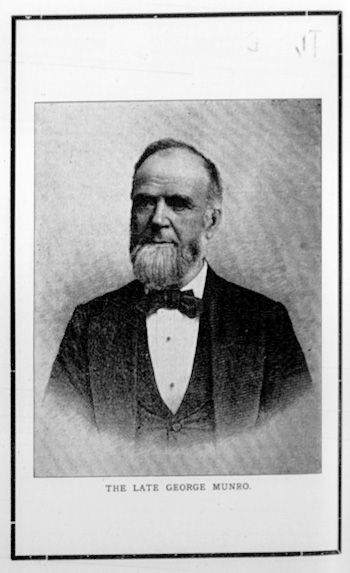

Other graduating classes have crossed the stage against sombre backdrops of a different sort. In 1896, spring convocation happened just days after the death of George Munro, a publisher whose generous donations helped save Dal during grave financial times for the university in the late 1870s.

Munro’s death at 70 struck the university community hard at the time, resulting in a “quieter and less public” convocation with “the character of a memorial service,” according to a report in the Gazette.

Munro’s death at 70 struck the university community hard at the time, resulting in a “quieter and less public” convocation with “the character of a memorial service,” according to a report in the Gazette.

Although Munro himself had no direct affiliation with Dal, discussions with his brother-in-law (a member of the Board of Governors at that time) encouraged him to support the university. He ended up donating hundreds of thousands of dollars — millions in today’s currency — over the years to set up several research chairs and bursaries, the latter of which no doubt helped many in the Class of ‘96.

"Though he cannot appear amongst us again, he cannot be forgotten," said Reverend Robert Murray in an address at that year's convocation. "He was a kindly helper of students. He opened to many a deserving youth the glorious portals of knowledge, and made possible careers of incalculable usefulness.

“You, ladies and gentlemen of Dalhouise, you and your predecessors and successors have the name of George Munro engraved upon your grateful hearts and souls. In your gratitude and love he has a precious monument which rust cannot corrode, and which the sharp tooth of time can never mar."

The changing face of graduates

Just as the tenor of convocation ceremonies shifted through the years, so too did the composition of graduating classes.

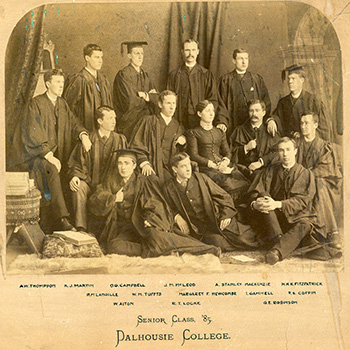

In 1881, Dal admitted two women into its ranks. One of them, Margaret Florence Newcombe (left, middle individual in the middle row), went on to become the university’s first female graduate. At convocation in the spring of 1885, Newcombe left not only with her Bacehelor of Arts degree in hand but also with two academic prizes for German and political economy. She went on to become principal of the Halifax Ladies’ College.

In 1881, Dal admitted two women into its ranks. One of them, Margaret Florence Newcombe (left, middle individual in the middle row), went on to become the university’s first female graduate. At convocation in the spring of 1885, Newcombe left not only with her Bacehelor of Arts degree in hand but also with two academic prizes for German and political economy. She went on to become principal of the Halifax Ladies’ College.

About a decade or so later, a man by the name of James Robinson Johnston also made history at Dal, became the first African Nova Scotian to graduate from university. Johnston first entered Dal at 16. He completed a Bachelor of Letters degree in 1896 and a Bachelor of Laws degree two years later before going on to become a successful military and criminal lawyer.

The Halifax Herald called him a “pre-eminent citizen” and “ornament” to the Bar Association of Nova Scotia during his years of practice. In 1991, a research chair in Black Canadian Studies (the only one of its kind in the country) was set up in Johnston's name — a testament to the Dal grad’s lasting influence on the university and the wider community.

As the years passed, Dal welcomed more women and students of African descent into its halls. In the early 1970s, the university launched its Transition Year Program that helped offer a supportive path for individuals from marginalized communities — particularly African Nova Scotian and Indigenous students — a path to a university education.

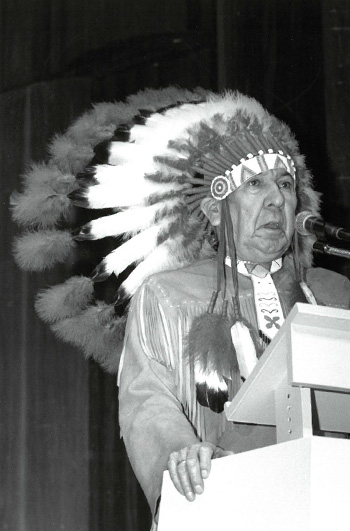

Dalhousie News characterized the convocations in the spring of 1990 as “something of a watershed” moment for Indigenous graduates. Eight Indigenous students received degrees (one in arts, seven in social work), Mi’kmaq grand chief Donald Marshall Senior (right) gave an invocation and benediction in the Mi’kmaq language, and two of the five honorary degree recipients were from Indigenous communities: Viola Robinson of the Native Council of Nova Scotia and Ontario ombudsman Roberta Jamieson.

Dalhousie News characterized the convocations in the spring of 1990 as “something of a watershed” moment for Indigenous graduates. Eight Indigenous students received degrees (one in arts, seven in social work), Mi’kmaq grand chief Donald Marshall Senior (right) gave an invocation and benediction in the Mi’kmaq language, and two of the five honorary degree recipients were from Indigenous communities: Viola Robinson of the Native Council of Nova Scotia and Ontario ombudsman Roberta Jamieson.

Jamieson, the first Indigenous woman to become a lawyer in Canada, implored the graduates assembled for the law school convocation to engage in the issues of the day and resist the urge to conform. She said changes to the law were beginning to bring about change and increased pressure on institutions to open up to more women and ethnic minorities presented opportunities to “contribute to the richness of our experience.”

Missing out on those opportunities would be “nothing less than shirking our responsibility,” Jamieson said. “We can’t afford outmoded ideas as we move toward the 21st century.