Like so many kids who came of age during the 1960s space race, Kathryn Sullivan was drawn to the stars.

“I’d grown up glued to the television set when any of the earlier space program things were on, or any of the Jacques Cousteau shows for that matter,” she said. “What had always excited me was this notion that there were some group of people whose lives consisted of going on these great adventures… Who they were, what they did, how to become one, I didn’t really know. I was just drawn to the adventure of it all.”

In time, Dr. Sullivan’s adventures would have her soaring into orbit, walking in space, launching the Hubble Telescope and eventually ending up in charge of one of the largest and most important scientific agencies in the U.S. government. But first, her adventures took her to Dalhousie, where in 1978 she graduated with her PhD in Geology from the Department of Geology, now known as the Department of Earth Sciences. (She also received her first honorary degree from Dalhousie, in 1985.)

This week, Dr. Sullivan returned to Dalhousie — by her recollection, her first time visiting Halifax in about a decade. Over the course of her two days on campus, she delivered the annual student-organized Gordon A. Riley Memorial Lecture in the Department of Oceanography, took part in a coffee chat and panel discussion with Dal students and faculty about women in the sciences, and delivered a public lecture titled “Looking at Earth” to a packed house in the McCain Building’s Ondaatje Hall Tuesday night. She also sat down with Dal News for an interview about her career.

This week, Dr. Sullivan returned to Dalhousie — by her recollection, her first time visiting Halifax in about a decade. Over the course of her two days on campus, she delivered the annual student-organized Gordon A. Riley Memorial Lecture in the Department of Oceanography, took part in a coffee chat and panel discussion with Dal students and faculty about women in the sciences, and delivered a public lecture titled “Looking at Earth” to a packed house in the McCain Building’s Ondaatje Hall Tuesday night. She also sat down with Dal News for an interview about her career.

Dr. Sullivan said she had a great time connecting with the students she met and witnessing their passion for oceanography (which she considers her primary discipline), earth sciences and science in general.

“All of them, in the work they’re in, have some fascination with the ocean, or some fascination with the planet more broadly, so there’s a lot of great passion, intensity and curiosity to what they’re doing,” she says. “And it’s wonderful to see how gratified they are by these challenges they’re involved in.”

From textbooks to space telescopes

Dr. Sullivan first learned about Dalhousie when she was an undergrad student on exchange in Norway.

“I was following the articles just beginning to come out about sea floor spreading. That whole revolutionary idea of how the ocean works and how the planet works was unfolding before my eyes as a young third-year student. The epicentre of the story was the North Atlantic, and it was clear there were still a lot of fascinating things to figure out.”

One of the groups heavily involved in that emerging research was a team of scientists at Dalhousie University and the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, including geology professor Fabrizio Aumento. Their reputation is part of what brought Dr. Sullivan to Dal for her graduate studies, where her eventual PhD project studied the geology of Newfoundland sea mounts. “I liked the feel of Halifax, the culture of it. The department was very collegial… it was an easy place to fit into.”

It was around that time in the late-1970s that NASA began to once again ramp up astronaut recruitment, with an eye to the forthcoming space shuttle program. For Dr. Sullivan, it was an opportunity she had to pursue.

“I knew they’d be swamped with applications, and they didn’t need many people, so they’d tell most people ‘no.’ But if they said ‘yes,’ I’d get to actually see the earth with my own eyes from orbit. And that wasn’t an opportunity I was going to pass up — you could have told me the odds were one in 200 million and I would have applied, because that means they’re not zero.”

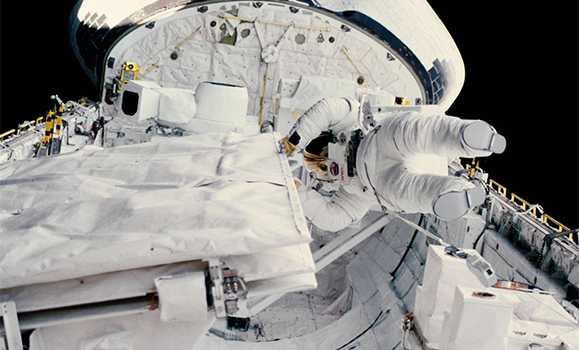

Kathryn Sullivan in spacewalk in 1984. (Photo courtesy NASA)

She was accepted right out of her PhD studies — one of the first six women ever to be admitted to NASA’s astronaut corps. Over the next 15 years she would take part in three space flights. On the first in 1984 aboard the Challenger, she earned the distinction of becoming the first American woman to walk in space. On her second mission in 1990 aboard the Discovery, she helped deploy the Hubble Space Telescope, one of the largest and most versatile telescopes ever put into orbit and still a vital research tool for astronomy more than 25 years later.

And what about that view of the Earth from orbit she was looking for?

“It will literally take your breath away. It’s stunning.”

Civilian leadership

After her third space flight in 1992, Dr. Sullivan began to consider life after NASA. She said she could have probably spent the rest of her career in “former astronaut” mode, getting paid to tell stories and share photos of her experiences. But she knew that wouldn’t be enough for her.

“The vantage point from space — the sense of intersection and connection you clearly have, just with your own eyes, even without advanced instrumentation — was so powerful,” she said. “I wanted to shift gears and somehow get into the field or get into roles where I was helping make that perspective matter.

“I knew I’d probably never be doing anything ever again that had such cachet, got such sizzle and big headlines. But I’d had enough experiences before I went to space that that I knew that while being an astronaut might have been the biggest headline I will ever have, it is far from the only intriguing or challenging or worthwhile thing to do on Earth.”

After leaving NASA, she made her way to the National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration (NOAA) to serve as its chief scientist. From there, she spent a decade as president and CEO of one of America’s leading science museums — the Center of Science and Industry in Columbus, Ohio — before becoming inaugural director of the Battelle Center for Mathematics and Science Policy, based at Ohio State University’s School of Public Affairs (which, appropriately, is named for a fellow astronaut: John Glenn).

In 2011, Dr. Sullivan was nominated by the White House as assistant secretary of commerce for environmental observation and prediction and deputy administrator of NOAA. The multifaceted science-based services agency employs nearly 20,000 people, has a budget just shy of $6 billion and includes such important departments as the U.S. National Weather Service, the National Fisheries Service, the National Ocean Service and more.

In 2011, Dr. Sullivan was nominated by the White House as assistant secretary of commerce for environmental observation and prediction and deputy administrator of NOAA. The multifaceted science-based services agency employs nearly 20,000 people, has a budget just shy of $6 billion and includes such important departments as the U.S. National Weather Service, the National Fisheries Service, the National Ocean Service and more.

“Our mission truly runs from the surface of the sun to the bottom of the sea,” said Dr. Sullivan.

In 2013 she took over as administrator, NOAA’s highest position, on an acting basis, and was subsequently confirmed to the role proper by the U.S. Senate in March 2014. That same year, she was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people. Among her many other honours: induction into the Astronaut Hall of Fame, membership in the National Academy of Engineering, induction as a fellow of the American Meteorological Society, and the Rachel Carson Award for her environmental leadership.

Looking at our planet in new ways

Dr. Sullivan’s visit to Dal was hosted by the Dalhousie Oceanography Student Association (DOSA), which invited her to campus for its Riley Memorial Lecture.

“As an accomplished scientist and astronaut dedicated to bridging the gap between science and society, Dr. Sullivan is truly an inspiration to us all,” says Jenna Hare, president of DOSA and PhD candidate. “With the Riley Lecture, we’re reminded of the great places our degrees can take us. Dr. Sullivan showed us that the possibilities are endless.”

Many students also attended Tuesday’s panel discussion and coffee conversation on the topic of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) careers. Other panelists in addition to Dr. Sullivan included Dal faculty members Katja Fennel (Oceanography), Stephanie Kienast (Oceanography), Sophia Stone (Biology) and Becky Jamieson (Earth Sciences), who’s been friends with Dr. Sullivan since they were college roommates.

A key theme that came out of the discussion was the importance of women having the confidence to show leadership and take charge of their careers and ambitions — a message Dr. Sullivan embodies, and was on full display in her public lecture.

In part of her talk, she walked the audience through various data-driven ways of looking at the Earth and its various systems: sea floor charts, satellite images of phytoplankton blooms, sea-surface temperature maps. She said that from outer space to the bottom of the sea, we have vantage points of our planet far beyond anything previously available in all of human history.

“NOAA is a place that works to connect this kind of capacity to the challenges and issues that face the planet every single day, whether that’s protecting public safety, providing information to guide resource use decisions, shape economic opportunities,” she said. “We like to call it ‘environmental intelligence’ — it’s measurements, plus scientific knowledge, plus computational capability to produce information that is pertinent to a decision facing someone today.”

And, of course, she shared several views of earth from orbit, taken from her weeks spent soaring above our atmosphere. She acknowledged, though, that no on-screen image can truly compare to the experience of being there in-person.

“Looking at a movie can never give you the understanding of what it’s like to be looking at it yourself — not because it looks that different, but because it’s about what it took to get there,” she explained. “We can watch the Olympics and feel empathy and excitement for the person standing on the gold-medal platform… but for them it’s not about being on the platform itself that’s special. It’s that moment, and everything you invested to get to that moment, that makes it meaningful.”