A design for a unique charcoal press by Dalhousie Engineering student Keilah Bias is not only winning awards, but also praise from a village halfway around the world.

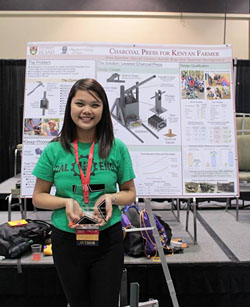

In June, third-year student Keilah Bias and her team won first place in a design competition at this year’s American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition in Seattle, Washington.

In June, third-year student Keilah Bias and her team won first place in a design competition at this year’s American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference & Exposition in Seattle, Washington.

“It was awesome to come in first place,” says Keilah. “My teammates felt we had a strong chance of winning. I tend to take a more conservative approach and didn’t want to get my hopes up, so I was excited and surprised when I found out we had won.”

A real-world application

Keilah and her team had originally designed the charcoal press for their second-year engineering design project at UPEI in 2014. That same year, the team’s professor, Libby Osgood, took a prototype to Mikinduri, Kenya, a small, remote village in eastern Africa, on her annual volunteer trip with the Mikinduri Children of Hope (MCOH) organization. While there, Prof. Osgood asked villagers to put the press to the test.

“The people of Mikinduri need fuel for cooking, but their process of making it is very tiresome and ineffective,” explains Prof. Osgood. “They use wood and only end up with small two-inch-by-one-inch briquettes. Deforestation is a big problem in Kenya and we wanted to determine if the charcoal press designed by Keilah and her team would be a better alternative.”

Prof. Osgood gathered video feedback to share with Keilah and her team via Skype, encouraging them to enhance the design to better meet the community’s needs.

“As soon as we saw the possible impact the design could make to society" says Keilah, "we thought, ‘Ok, we’re not just going to abandon the design simply because it was a class assignment: we can improve it, complete it, and send it back to Kenya with the MCOH volunteers the following year.’”

What makes the press so effective? Its efficiency: by using waste materials like dried cornstalks and turning them into charcoal briquettes, fewer trees have to be cut down.

“We actually improved their efficiency by about 60 times because you can make 16 longer and bigger briquettes at once,” says Keilah. “This method produces more charcoal, giving the people of Mikinduri the opportunity to have income."

First-hand experience

After the team revamped the design, Prof. Osgood offered Keilah the opportunity to travel to Mikinduri as a volunteer with MCOH. While there, she conducted demonstrations on making charcoal briquettes from materials such as cassava and banana leaves. Her presentations and the common-sense design quickly won people over.

“It was definitely a learning experience to see how different it is to design something remotely from your end user,” says Keilah. “Our drawing package was very sophisticated. We outlined specific tools needed, specific tolerance, safety factors, and all of those sorts of things. Some aspects of our initial design didn’t work well in Kenya, but through reevaluation we came up with a successful solution for the people in Mikinduri.”

Keilah also worked with students at Athwana Polytechnic to teach them how to make the press with the materials they had available to them. Prof. Osgood was particularly taken with Keilah’s ability to engage students and show them that both girls and boys can be engineers.

Keilah also worked with students at Athwana Polytechnic to teach them how to make the press with the materials they had available to them. Prof. Osgood was particularly taken with Keilah’s ability to engage students and show them that both girls and boys can be engineers.

“She was accompanied by a translator, and managed the modification of the press, purchasing materials, and working with Kenyans. The rest of us were in pairs, so I was impressed by her independent abilities. I see great things for her future as an industrial engineer.”

For Keilah, the time she spent in Kenya was a rewarding experience, and helped her realize what she wants to do with her career.

“I really want to teach engineering. I discovered that I’m very passionate about watching people learn and teaching people how engineering applies to almost everything in our life. I think teachers have the power to leave ripples that are reflected for eternity. And I want to be in a position to help others realize their dreams. I feel like, by deciding to be an engineer, I’ve taken on the responsibility to make the world a better place to live.”