Anatoliy Gruzd and his team at Dal's Social Media Lab are devising new ways to analyse us how social media influences society — and their latest work hits very close to home for the lab's director.

In a talk earlier this month, Dr. Gruzd applied his expertise in social media analytics to recent events in the Ukraine, his home country that he left a decade ago, to show that the role of social media in political movements is expanding and changing.

Dr. Gruzd's work focuses on analyzing data generated by online user activities to learn about how people communicate and interact via the Internet and what impact this has on society. One aspect of this research is analysing how different social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, are used to engage different groups of people.

“We at the Social Media Lab are interested in examining how different platforms enable online and offline groups to grow, how social media can be used to track disasters and other events in real time, and how information and misinformation are spread online,” says Dr. Gruzd, whose lab is located in the Faculty of Management’s School of Information Management.

A new way of tracking social movements

Social scientists have been studying the formation and patterns of social movements for decades but the advent of social media has brought new kinds of information into the mix. Two big areas of focus are “metadata” and “big data.”

Metadata is exactly what it sounds like: data about data. To use a social media example, when a news source like the BBC tweets a story, it can be retweeted, favourited and replied to by any number of different user accounts. Metadata in this situation refers to, for example, the number of retweets/favourites/replies and information on the accounts that did so, such as location or language used.

With the proliferation of social media, this kind of data can quickly become too large to be manageable by traditional programs. When this happens, it's often referred to as “big data.” Dr. Gruzd and his colleagues are working to develop new tools to analyse and visualise big data to learn how social media are influencing the way people organize and act.

The number of tweets that mentioned Ukraine (in Ukrainian) over time.

The application of this analysis quickly became apparent in Dr. Gruzd's talk. Using visualizations created by his software, Dr. Gruzd showed the evolution and trends of the conflict in the Ukraine peaking in February of this year. One diagram shows a spike in Twitter activity when the clashes in Kyiv turned deadly on February 18, followed by a spike twice as large when Russia approved the use of military force in Ukraine. This demonstrates growth in interest and involvement.

Revolutionary implications

Dr. Gruzd also pointed to three interesting changes in this particular social media-fuelled revolution compared to others in the recent past. First, a much larger amount of content generated about the crisis in Ukraine was in English, as opposed to a local language such as Ukrainian or Russian.

“We are often seeing messages in either English or both English and Ukrainian so that the information can be picked up by Western supporters and media,” Dr. Gruzd explained. “The movement has realized that if they want to tell the world what is really happening in Ukraine they have to have English content.”

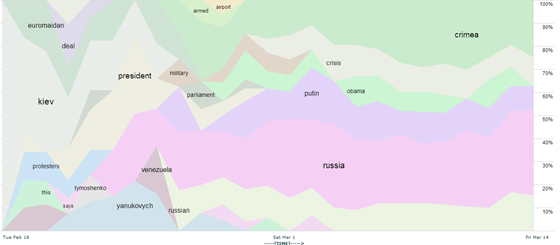

Frequently used topics over time mentioned in English tweets about Ukraine posted between February 18 to March 14, 2014. The figure shows how the discussion moved from the protests in Kiev to the events in Crimea.

Second, the movement in Ukraine is actively using multiple social media platforms simultaneously, whereas in the past the focus has been primarily on a single platform such as Facebook (in Tunisia) or Twitter (in Iran). Different platforms allow like-minded people to find each other and interact in different ways, from hosting news programming online when TV stations are shut down, to expeditious organization of movement in 140 characters or less.

Third, all kinds of actors are now using social media. “In previous movements, social media was dominated by younger people who were not part of the establishment,” says Dr. Gruzd. “In Ukraine, it is being used by the government, elected officials, and even law enforcement agents who track movement to deescalate clashes.”

Dr. Gruzd says there is more qualitative analysis to come and is interested to see if new social media platforms emerge as a result of these developments. “Being successful as a new platform takes a lot of energy to reach critical mass and you often have to be the first to the market, but it is possible that something will emerge that addresses shortcomings of the current sites.”

For more information about Dr. Gruzd and the Dalhousie social media lab, follow Dr. Grudz on Twitter or visit the lab's website.