Sexual assault. It’s an issue that has everyone talking at the moment — and it’s not an easy one to talk about.

May is Sexual Assault Awareness month, organized by Halifax’s Avalon Sexual Assault Centre, which raises awareness about the impact that sexualized violence has on our communities.

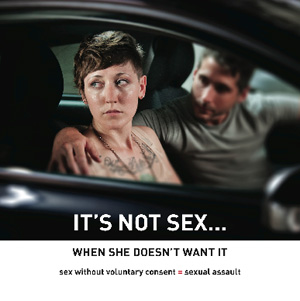

Earlier this month, Halifax Regional Police announced a second round of the “Don’t be that guy” poster campaign, using materials that have been a familiar around campus over the past year. Originally created by the Sexual Assault Voices of Edmonton, the posters were adapted for Dalhousie by the Office of Human Rights, Equity and Harassment Prevention and Dal Security.

“Nova Scotia has the highest rate of sexual assault per capita in Canada, and the majority of assaults occur to females between the ages of 13 and 25, so the university population is a vulnerable population, just given the demographics,” explains Gaye Wishart, Dal’s harassment prevention/conflict management advisor.

“Don’t be that guy” — or a bystander

While many awareness campaigns about sexual assault target women — advising them on personal safety — this one turns the tables to focus on men.

“All too often, these campaigns can have an erroneous ‘blaming’ message: if you hadn’t done this, the situation wouldn’t have happened,” says Mike Burns, Dal’s director of security. “But this turned the focus around to the male perspective: there’s a responsibility on your part to ask for and receive valid consent.”

“All too often, these campaigns can have an erroneous ‘blaming’ message: if you hadn’t done this, the situation wouldn’t have happened,” says Mike Burns, Dal’s director of security. “But this turned the focus around to the male perspective: there’s a responsibility on your part to ask for and receive valid consent.”

The Dal editions feature a second message as well — not just “Don’t be that guy,” but “Don’t be a bystander.” The idea is that we all have a responsibility to stop sexual assault, whether that means asking a housemate to back off if they’re being too aggressive with someone, or making sure a friend gets home safely if they’ve had too much to drink.

“That’s a key part of the message,” says Burns. “As much as we talk about Rohypnol and other chemicals, alcohol is actually the number one date-rape drug… We deal a lot on campus with 17, 18-year-olds away from home for the first time, and we’d be naïve to think there wouldn’t be alcohol involved in their social lives at times. That’s why it’s important to say to the men on campus, ‘Just because she can’t or isn’t saying no, that doesn’t mean you have consent.’”

Wishart says the campaign also helps illustrate that the majority of sexual assaults happen between individuals who know each other.

“It’s not ‘stranger danger,’” she says. “It’s not somebody jumping out of the bushes at you. It’s acquaintances, sometimes friends. Most of the time, sexualized violence occurs with someone that you know.”

Getting help, finding support

In addition to the poster campaign, the Office of Human Rights, Equity and Harassment Prevention, Dal Security and Residence Life are currently developing a sexual assault protocol for campus.

“If someone is sexually assaulted, is the first person they’re going to come and see me?” asks Wishart. “Probably not. Our office is certainly open and willing to speak to whomever, and people do come in and report, but they’re more likely to report first to a [resident assistant], a friend, South House or someone in Health Services. So we want to make sure everyone has access to a protocol on how to respond appropriately in a way that’s not going to be more damaging to the individual, and which lets them know what resources are available to them.”

The university is also developing a system for anonymous online reporting for sexual assaults: a way for individuals to report an incident if they’re not comfortable doing so in person. The individual who’s reporting would be given an overview of the supports and resources available in the community, and their report would give us more information about assaults on campus.

“If someone is not comfortable coming forward, it’s still important that we know about it,” explains Burns. “For example, if we know there have been four incidents in the past three weeks in the same area on campus, then we’ve got a real community safety problem to address. That knowledge is useful even if an individual doesn’t want to come forward.”

When students do report an assault, either to Wishart’s office, to Dal Security or another unit on campus, the common message is support.

“Sometimes students just want to tell their story,” says Wishart. “From our end, we want to make sure they’re safe, that they have the appropriate medical follow-up and, from there, we’re able to chat about next steps — whether that’s the legal route, counseling, a no-contact agreement or anything else they need.”

Speaking up

Above all else, Wishart and Burns hope these sorts of efforts get the Dal community talking about a topic that, all too often, stays far too quiet.

“With the Rehtaeh Parsons case, which was a very horrific incident in the life of the Halifax community, this is nothing new,” says Wishart. “I’m the chair of the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre board and I can tell you, the staff at Avalon are hearing these kinds of stories very regularly.”

“The provincial government has come up with some short-term solutions but I think there needs to be a long-term strategy, focused on prevention and education as opposed to the counseling after the fact. That’s important, of course, but we need to do a better job educating youth about consent, about speaking up and not being a bystander in situations that are making them feel uncomfortable, for any number of reasons.”

Dal also continues to expand its first responder training, with support from Avalon, working with everyone from RAs in residence to orientation leaders. And this fall, look for a new set of posters around campus, focusing on encouraging bystanders to speak up about sexual assault.

“The idea is that if you see something, say something,” says Burns. “Sometimes all it takes is someone stepping into a situation when it’s just getting started and saying, ‘Leave her alone.” We want people to trust their instincts — they’re usually right.”