|

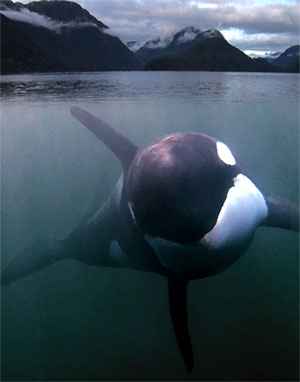

| From Saving Luna |

Three weeks stretched into three years. Filmmakers Suzanne Chisholm and Michael Parfit thought they’d be staying in Nootka Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, for a little while until they got their story written.

But they, like many people he came in contact with, were beguiled by the wayward killer whale named Luna who sought out human companionship after being separated from his pod.

With several National Geographic projects under their belt, the team imagined they would be able to keep their distance and remain objective observers in the controversy. Some locals were delighted by the sociable orca; others were alarmed, believing all human-whale contact should cease for Luna’s own benefit.

It was an impasse at the intersection of science and society.

“He really was amazing—seeking out humans not for food, but for friendship. He’d just tug at your heart strings,” says Ms. Chisholm, who did her master’s degree in economics at Dalhousie more than a decade ago. She’s thrilled to be coming back to Halifax with her feature-length documentary in tow.

The film Saving Luna opens Friday, March 6 at Empire Theatres Bayers Lake for a week’s engagement. Ms. Chisholm will be in attendance at all screenings over the weekend to talk to filmgoers and answer questions.

|

On the phone from B.C., she says Saving Luna provokes a lot of questions from its audience, the most common being, “What is the right thing to do when humans come in contact with wild animals?”

It’s certainly a question that’s been asked many times in Atlantic Canada. Last summer, a young beluga whale dubbed Q became separated from its family pod and started making new, human friends off the coast of Cape Chignecto on the Bay of Fundy. Before that, there was Poco, who sought out human company near Pocologan, N.B. in the Bay of Fundy, and Wilma, who delighted people for several years in Chedabucto Bay, Cape Breton.

In Luna’s case, the more officials tried to keep the young whale separated from humans, the more he would seek them out: nudging their boats, trying to engage them in play and expanding his territory. Ms. Chisholm says the charismatic creature was “biologically hard-wired to be social.”

“No matter what they did—there was literally a police presence patrolling the inlet—Luna was desperate for contact,” says Ms. Chisholm, from Sydney, N.S. “It was almost haunting when he would seek you out and look you in the eyes. We were so in awe of him and yet sad that he didn’t have other whales to be with.”

Saving Luna has been shown at film festivals worldwide and now the documentary is opening at theatres across Canada. Ms. Chisholm says that doesn’t happen to documentaries very often.

“It is hard to see documentaries on the big screen—people have this preconceived notion that if it’s a documentary, it’s boring,” she says. “But with Saving Luna, there are so many twists and turns, it’s almost like a drama. And plus we have this incredible character, Luna.”

LINKS: Killer whale barked like a sea lion in National Geographic | Encounter with Luna is a lesson in stewardship in the Seattle Times

TRAILER: Saving Luna