|

| Prof. Steve Shaw and nature's champion high jumper, the spittlebug. (Photo illustration by Danny Abriel) |

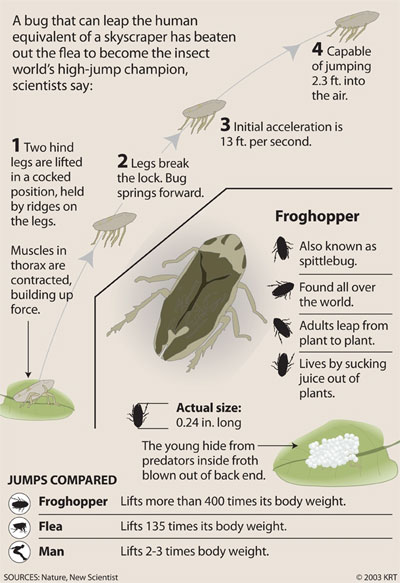

Before now, the spittlebug’s main claim to fame has been its ability to blow bubbles out of its backside.

But now the lowly spittlebug (so named because it can whip up a frothy covering that looks like human spit to protect itself) has been crowned nature’s top high-jump champ. Researchers from Cambridge and Dalhousie universities discovered that the tiny insect leaps more than 70 centimetres in a single bound. This amounts to 100 body-lengths, out-distancing its closest rival, the flea.

For comparison, the ability to leap 100 times the height of the average human would enable a jumper to clear an office tower as high as Fenwick Tower.

But that’s not all: the researchers have now figured out how it’s done. Spittlebugs—also known as froghoppers—use a catapult-like mechanism to achieve their jumping prowess. Energy generated by the slow contraction of a huge bank of muscles is stored in an elastic internal structure, then released in less that a millisecond to power the explosive extension of the hind legs.

“They jump like little bullets,” says Steve Shaw, a professor with the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience. “It’s a last ditch escape response, otherwise the bug becomes bird food.”

Dr. Shaw collaborated on the study, published in a recent issue of the online journal BMC Biology, with Malcolm Burrows, current head of the Zoology Department at the University of Cambridge. The two, friends since they first overlapped as neuroscience graduate students at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, spent August afternoons sweeping the long grasses with nets at York Redoubt, the 18th century military fort overlooking Halifax Harbour, returning to Dalhousie to analyze the specimens they collected.

|

Under the microscope, a rubber-like protein known as resilin originally thought to power the jump alone can be located by its bright blue fluorescence under illumination with ultraviolet light. Resilin, a stretchy protein also found in the wing-hinges of dragonflies, is an almost perfect rubber that after being stretched to more than twice its length for up to several months, will return completely unscathed to its exact original shape.

But the resilin alone isn’t enough to put the hop in the froghopper. The stretchy resilin is set against hard cuticle, the insect’s body armor which is stiff enough when bent to absorb all the muscle energy, retaining the tension that will power the jump. The authors compare the spittlebug’s jump mechanism to the recurved compound bows carried by Genghis Khan’s Mongol cavalry—short, light but powerful weapons that made these mounted archers such a formidable fighting force in the 13th century. Their bows were also made of a composite laminate: most energy was stored by flexing the bow’s hard back of horn or bone, stiff but brittle, while elastic recovery was afforded by animal sinew glued on the front. The Mongol riders could discharge their high-tech weapons while riding at full tilt, making them a highly mobile and deadly mounted archer force not seen before in warfare.

Could this system be adapted as a commercial proposition for human jumpers? “Well, even if Nike or Reebok found a way to put resilin in shoes for basketball players,” says Prof. Shaw with a smile, “the downside would be that they’d go on rebounding forever so never wear out. Like the fabled re-usable match, where’s the money in that?”