|

| Satellite sensor gives scientists an unprecedented view of ocean changes (NASA) |

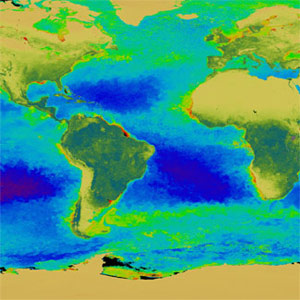

To the human eye, seawater appears a murky green, deep blue, luscious turquoise or often a mysterious grey.

But seen from a special satellite sensor orbiting Earth, the shifting colours of the world’s oceans can actually indicate the planet’s biological response to such stresses as climate change and pollution.

“Greener shades are indicative of richer, more biologically productive marine areas,” says Dalhousie oceanography professor Marlon Lewis, a key member of the NASA team that put this technology into space in 1997.

The SeaWiFS instrument (Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor) circles the planet 14 times daily. Gathering daily data over land and sea, it gives scientists a global picture of variations in biological processes over space and time – something that was impossible until a decade ago.

One thing measured through colour is the distribution of phytoplankton, one-celled organisms that are key indicators of ocean health. The microscopic plants absorb carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, converting it with water and sunlight into carbon-based biomass, which supports almost all life on Earth.

“The fish have to eat something,” explains Dr. Lewis. “It’s like we depend on grass to feed the cattle on land. Phytoplankton are as basic as that to the overall health of the marine food chain.”

'Rightfully proud'

He joined other scientists last week at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland, for a special 10th anniversary celebration of the sensor. “It’s a remarkable achievement, and it’s something NASA should be rightfully proud of … it has done for ocean science what the PC has done for computers,” he said during a panel discussion, which was televised and webcast live on NASA TV.

Dr. Lewis recalled “an enormous amount of work at the outset,” at a time when NASA’s primary focus was space exploration. Taking a two-year leave of absence from Dalhousie in the late 1980s, he worked as program officer at NASA Headquarters, where he was responsible for ocean colour research and planning the SeaWiFS program.

“The applications for this data turned out to be much broader than we ever expected at the time,” adds Dr. Lewis, who is also chairman, CEO and chief scientist of Satlantic Incorporated.

Tracking vanishing ice

The sensor is now tracking the Arctic’s vanishing ice, and has been used in algae bloom experiments. It identified factors in a phytoplankton bloom that killed seabirds in the Pacific in 2005, and has also helped scientists better understand the ocean’s response to El Nino and temperature change.

Its greatest legacy, says Dr. Lewis, is its wide reach. The ongoing data generated by the sensor is available to researchers of all types, including undergraduate students at Dalhousie. One current project at Dal involves monitoring the spawning of Atlantic cod off the coast of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, by cross-referencing SeaWiFS data with information coming in through fish tags in the new Ocean Tracking Network.

For more details on the sensor’s impact, visit http://www.nasa.gov/vision/earth/lookingatearth/seawifs_10th.html.