Impacting Lives

Advocating of for Neurodivergent-affirming Spaces with Lived Experience

By Kayla Warren

When I first learned about occupational therapy four years ago, I couldn’t have imagined myself as an occupational therapy student advocating for neurodivergent-affirming practices. Instead, I was simply hoping to reduce my anxiety.

My occupational therapist helped me understand that most of my anxiety was triggered by too much sensory input and helped me develop sensory modulation skills and tools to use in overstimulating environments. This positive experience prompted me to learn more, which led to my graduate school application. Now, I use my knowledge and experiences to promote access to accommodations, advocate for neurodivergence acceptance, and suggest neurodivergent- affirming practices.

Access to Regional Platforms Granted Through Advocacy

I have faced multiple barriers during my education. Each experience has reinforced my desire to increase accessibility for future students. Like others (Bulk et al., 2017), I want to raise awareness about the deeply rooted societal stigma around neurodivergence, mental illness, disability, and the inherent ableism in our society, while simultaneously challenging it. Much like my female role models in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) who felt alone in male-dominated fields, I entered the rehabilitation field without knowing neurodivergent academics who could be role models for me. I admire how women in STEM tell others about their journeys, and so I feel it is essential for me to speak up about how neurodivergent people can work as health care providers.

I have been open on social media and Newfoundland news platforms about my university experience and the invisible labour required to address disability-related barriers. These advocacy efforts led to an opportunity to speak on a panel created by Autism Society of Newfoundland and Labrador (ASNL) about my experiences with autism and what towns and schools can do to support Autistic people. This panel included the president of Memorial University of Newfoundland, a pediatrician from the Janeway Children’s Health and Rehabilitation Centre, and a community leader.

I was nervous about potential pushback for speaking out about the barriers I encountered in the occupational therapy program. Instead, speaking out led to an invitation to join an adult autism spectrum disorder working group with other occupational therapists in Newfoundland and Labrador, as a consultant with lived experience navigating the health care system.

Key Messages Within My Advocacy Work

Accommodations don't make an environment accessible or equitable

Accommodations are both difficult to access and an insufficient measure to ensure equity. Medical documentation is generally the first step for accessing services, which can be time-consuming and costly. And even with documentation, I still needed to advocate to get the supports I needed for class and fieldwork. In the occupational therapy program, with its focus on equity and justice, I was surprised by the difficulties I encountered. Some of my experiences are similar to experiences described by the “professional misfits” who participated in Beagan et al.’s study (2022), who state that “while those who fit may experience professions as open and committed to diversity, those who constantly come up against the institution may feel the abrasiveness of institutionalized whiteness, upper-class-ness, able-body- mind-ness, and heteronormativity” (p. 3).

Accommodations also don’t address the underlying inaccessibility in environments historically designed to oppress people who did not fit into the dominant culture (Pooley & Beagan, 2021). Occupational therapists often advocate for accommodations on an individual level so clients will have their needs met and can be themselves at their school or workplace. The fact that some occupational therapists hide aspects of their own identities suggests that accommodations are not enough to lead to equity (Beagan et al., 2022; Bulk et al., 2017). Programs must consider options other than accommodations to promote equity, such as part-time study options. While education programs emphasize the need to function in a full-time occupational therapy role across practice sectors, this model offers much less flexibility than the real world (Zafran & Hazlett, 2022). Following graduation, therapists can work part-time or full-time, in an area of practice aligned with their skills and abilities, and in environments that can accommodate fluctuating needs.

Greater acceptance of neurodivergence needed in multiple areas of society

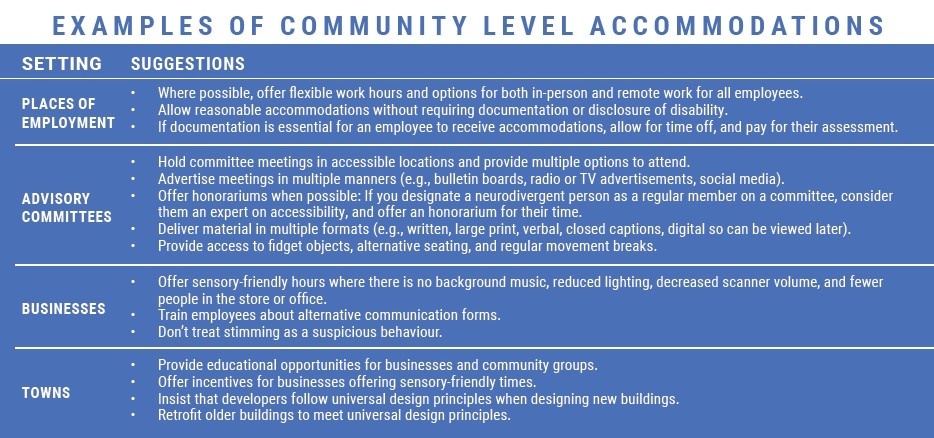

Neurodivergent-affirming practices in towns and businesses

During my ASNL panel presentation, I highlighted benefits of having neurodivergent people as employees and active members of the community (Krzeminska, et al., 2019). I also discussed neurodivergent-friendly ways of communication, such as not forcing eye-contact or supressing stimming, providing options to email rather than call, and using of alternative forms of communication. There are many other measures that the broader community can implement to increase accessibility for neurodivergent people. Most suggestions will benefit everyone. More accessible environments are both reflective of greater acceptance and offer greater likelihood of interactions between neurodivergent and neurotypical people, which also leads to acceptance.

Personally, embracing neurodivergence means moving away from the notion of neurodivergent people as broken neurotypicals that need fixing, and instead focusing on how society’s practices disable individuals (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2020). I — as do those in my peer community — view neurodivergence as an identity rather than a disorder. What makes neurodivergence disabling is when we are expected to act neurotypical around others and face bullying or heavy criticism when we do not.

Neurodivergent-affirming practices in education

When asked about neurodivergent practices within education on the panel, I suggested universal design for learning, which encourages a strengths-based approach and supports multiple learning styles (Dalton et al.,2019). Educators should focus more on what a student can do as opposed to what they can not. In elementary and secondary schools, measures can include allowing fidgeting (e.g., rather than encouraging quiet hands), incorporating movement breaks into lessons, providing alternative seating or standing desks, and allowing sensory breaks without earning them. For post-secondary students, programs can increase flexibility, such as offering online or in person synchronous and asynchronous classes and options to take programs with part or full-time schedules. To make this option more financially possible, the National Student Loans Service Centre allows students registered with a permanent or prolonged and persistent disability to be classed as full time with a 40% course load and allows a maximum of 520 weeks instead of the typical 340 weeks (Government of Canada, 2022). However, flexibility is still program dependent. Certainly, I am not the first person to struggle with the occupational therapy program’s courseload and there are multiple reasons that qualified students need part-time options to access a program. I am pleased to use my expertise to highlight areas where there is room for improvement. I hope that awareness about these issues will lead to change, even if it’s a slow process and there’s still a long battle ahead.

Health care settings benefit from neurodivergent-affirming practices

I’m glad I faced my fear of pushback and spoke on the panel. After the conference, a few occupational therapists approached me with positive feedback. On my next fieldwork placement, my preceptor remembered me, and asked to draw upon my expertise of navigating the health care system as an Autistic adult and join a regional adult autism spectrum disorder working group. She drew upon my strengths to adapt a pre-existing sensory modulation program designed for a mental health setting to be more inclusive for neurodivergent clients. There has been an increase in the number of neurodivergent-identifying adults seeking support for mental health concerns. As occupational therapists, we can respect our clients’ identities, even without formal diagnosis, and use evidence-based skills, such as those used for co-occurring mental illness, sensory processing differences, and environmental adaptations (Kirby et al., 2023). My role in the working group is now permanent. As a service user representative and community consultant, I identify current gaps and ideal solutions, and suggest services that are both beneficial and realistic within the public health care system’s constraints. I have drawn attention to the lack of services for people aging out of the pediatric system, the unclear pathway for an adult diagnosis, and the requirement of a diagnosis to access autism services. Solutions I suggested included: a program for continuing care into adulthood, neurodivergentinformed education for other health care professions, not gatekeeping services to only people with formal diagnosis, and assisting clients navigate the system if they decide to pursue an autism diagnosis.

In a recent initiative, therapists in the working group gathered feedback from clients about their assessment and intervention tools. They are now searching for evidence-based, neurodivergent-affirming alternatives, as well as beginning to modify their communication style as needed so clients can unmask.

Through my attention to advocacy, I found confidence to unmask more often, and neurodivergent clients tell me that my openness took the pressure off them to mask as well. I still feel pressure to mask neurodivergence with clients and co-workers to maintain the status quo. I make my decisions to unmask within the context of my professional responsibilities: to be client-centred and focus on equity and justice when advocating for allocation of resources (ACOTRO, ACOTUP, & CAOT, 2021). I also want to be an example that, even if it’s a slow process, speaking up can make a difference in the long term.

My experiences of encountering barriers in post-secondary and health care settings taught me the distinction between the tokenistic use of the words diversity, inclusion, equity, and justice, and living these ideals: making systemic changes and going against the grain to remove structural barriers designed to exclude those who are different. This knowledge will follow me for the rest of my career, and I will continue to apply the skills I have developed in future practice.

References

ACOTRO, ACOTUP, & CAOT.Competencies for occupational

therapists in Canada. https://caot.ca/document/7677/Competencies%

20for%20Occupational%20Therapists%20in%20

Canada%202021%20-%20Final%20EN%20HiRes.pdf

Beagan, B., Sibbald, K. R., Pride, T., & Bizzeth, S. R. (2022).

Professional misfits: “You’re having to perform … all week

long”. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(4), 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1933

Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., &

Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions of

autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29.

https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

Bulk, L. Y., Easterbrook, A., Roberts, E., Groening, M., Murphy, S.,

Lee, M., Ghanouni, P., Gagnon, J., & Jarus, T. (2017). “We are

not anything alike”: Marginalization of health professionals

with disabilities. Disability & Society, 32(5), 615–634.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1308247

Dalton, E. M., Lyner-Cleophas, M., Ferguson, B. T., & McKenzie,

J. (2019). Inclusion, universal design and universal design

for learning in higher education: South Africa and the United

States. African Journal of Disability, 8, Article 519.

https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v8i0.519

Government of Canada. (2022, August 9). How to apply. National

Student Loans Service Centre.

https://www.csnpe-nslsc.canada.ca/en/how-to-apply

Kirby, A.V., Morgan, L., & Hilton, C. (2023). Autism and mental

health: The role of occupational therapy. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 77(2), Article 7702170010.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2023.050303

Krzeminska, A., Austin, R., Bruyère, S., & Hedley, D. (2019). The

advantages and challenges of neurodiversity employment in

organizations. Journal of Management & Organization, 25(4),

453–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.58

Pooley, E. A., & Beagan, B. L. (2021). The concept of oppression

and occupational therapy: A critical interpretive synthesis.

Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 88(4), 407–417.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00084174211051168

Zafran, H., & Hazlett, N. (2022). This house is not a home: Rebuilding

an occupation therapy with and for us. Occupational

Therapy Now, 25(2), 5–7.

https://caot.ca/document/7758/OT%20Now_Mar_22.pdf

This article first appeared in OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY NOW July/August 2023 VOL 26.4. Permission for posting was granted by CAOT. CAOT holds the article copyright.