News

» Go to news mainRising from the Ashes through Higher Education and Family

Rising from the Ashes through Higher Education and Family (as related by his children)

Dalhousie University is celebrating the Indigenous Community Room opening on June 21, 2022, with the Prosper family in attendance. We graciously celebrate the gifts from the Prosper family and celebrate the contributions and life of alumnus James Prosper.

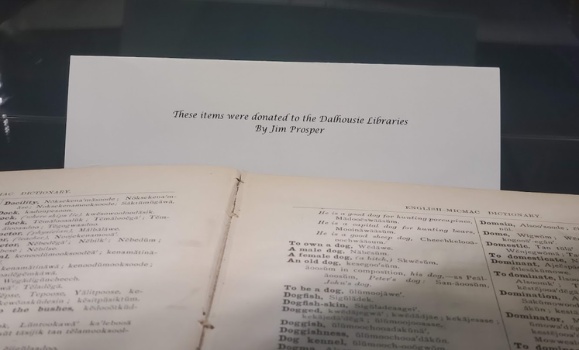

A part of his legacy, is the over 750 items that he and his family are donating to libraries at universities in Nova Scotia. Around 300-400 items can now be found in across Dalhousie Libraries on all campuses with 22 items living in the Special Archive for rare items. Some of these items, especially those relating to Mi’kmaw topics will be found in the Indigenous Community Room.

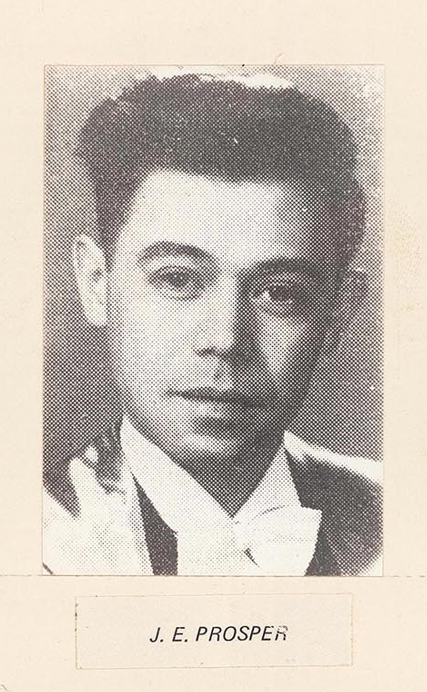

James Prosper (BEng ’52)

James was born in Halifax in 1925 to an unwed Indigenous mother and was put up for adoption. After several years at the Children’s Orphanage in Halifax, he was moved to the recently completed Indian Residential School in Shubenacadie where he found himself to be in the first cohort at the age of five.

James was born in Halifax in 1925 to an unwed Indigenous mother and was put up for adoption. After several years at the Children’s Orphanage in Halifax, he was moved to the recently completed Indian Residential School in Shubenacadie where he found himself to be in the first cohort at the age of five.

An orphan, James had a rather unique experience at the school. Unlike other children, he never returned to community and family during the holidays, save for his very first summer where, as a 5-year-old, the school was able to locate his mother and arrange for him to stay with her for a short time. For all other periods, he remained at the school full time until he was 18 years old, working the farm. Children were only to remain at the school until the age of 16, however, Sister Mary Charles developed a maternal relationship with Jimmy, as he was called in letters that continued to come from her well after he had left the school.

He speaks little of the now widely known abuse at the school, rather he speaks of Sister Mary Charles sending him to the public school in Shubenacadie, encouraging his education and defending his prolonged stay having nowhere else to go. Laughingly, he tells the story of discovering letters in the National Archives from the bureaucrats at Indian Affairs asking “how long is Jim Prosper going to be 16 years old”. James was known to be rather gifted in mathematics and well-known Mi’kmaq educator, Peter Christmas, remarked on how other children called upon James to help them with their math. James did not escape the cultural genocide, a key objective of the residential school system, but he did benefit from public schooling, something that most of the children were denied as chores often overtook studies.

At the age of 18, James enlisted in the war effort serving “overseas” in Newfoundland which had yet to join confederation. As a Communications Specialist, it is here where James developed an interest in electronics. When the war ended, and facing the option provided to servicemen of housing or education assistance, James chose to attend St. Francis Xavier College. The support of Father Fogarty at St. FX was instrumental to James’ early success in post secondary education. It was customary when pursuing a degree in Engineering, to continue studies at the Nova Scotia Technical College, now part of Dalhousie University. A rather unfortunate intersection of an unwarranted, inconclusive chest x-ray during a hospital visit with a friend, and a tendency to hypochondria, James’ education was delayed over a year with a stay in a sanitorium presumably with Tuberculosis without symptoms. Despite the setback, James graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Engineering in 1952 from what is now Dalhousie University.

James had a complicated upbringing, influenced by the realities of the residential school, the support of key figures primarily in the church and an unfulfilled relationship with his mother. James told his children that he wrote letters to his mother every week over his 13 years at the residential school. He never received a single reply. Whether replies were not written, or the original letters were never sent is not clear. After years of what appeared to be rejection from his mother, she did in fact try to meet again with James when he was at the sanitorium. Hurt by her lack of contact, he refused to see her. Tragically she died two years later, and he never got a chance to understand his mother’s full story. Years later he reconciled with his mother in a heart wrenching act, witnessed later with his children where he commissioned a headstone on his mother’s unmarked grave that read “dedicated by a contrite son”.

James went on to work at Canadian Arsenals in Toronto, a key supplier to the Department of National Defence and ultimately landed a job as the chief engineer at the Communications Security Establishment, a little known and secretive federal department, involved heavily in the cold war at the time. He became very respected in his field of electronic shielding, something important in communication espionage. Of course, this is all speculation on the part of his children who often probed their dad on what he did for a living. James respected his oath of secrecy even to this day at the age of 97, living in a care home.

In discussion, James’ children have come to several conclusions on their father’s life. First, and most importantly, his children have been his life. In contrast to a lack of a traditional family in his own upbringings, he somehow took the best of all his experiences to raise and guide a family with solid values and a strong recognition of who they are as Indigenous people from a very early age. That is not to say that there were not peculiarities as second-generation survivors of the residential school system, however, all his children have been fiercely proud of their Indigenous heritage despite it leading to some ridicule as kids and the occasional barrier of outright racism. Secondly, he instilled understanding that it was education that raised their father up out of his past and the same would be expected of them. Following in his tradition, his two sons, Ron and Rob both graduated university and their sister Lisa completed advanced degrees. In turn, their kids have gone on to successfully complete degrees, advanced degrees and certifications in diverse fields that include law, accounting, social science, engineering and communications.

The building of the archives and giving back to indigenous communities

Later, in retirement, James made huge efforts to try to influence the trajectory of Indigenous peoples in Canada. He reconnected with Mi’kmaw communities, made blueberry picking pilgrimages, supported education efforts and most importantly dove into research on Indigenous history. In doing so he completed and shared submissions to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and amassed a world class library of Indigenous history. When the Shubenacadie Residential School burned down in 1986, he collected bricks to mark the occasion. He also came into possession of the original architectural plans for the building of the school where he lived for 13 plus years. These he donated to the Mi’kmaq Heritage community who will be using them as part of a National Historic Sites initiative on residential schools. The site of Shubenacadie Residential School was designated a National Historic Site in 2020.

Ron, Rob and Lisa have found their own unique ways to advance the interests of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Ron was an advisor to the first Inuit Member of Parliament and later became a senior executive at Human Resources and Social Development Canada where he championed inclusive hiring and aboriginal circles within the department, participated on a table of Indigenous Executives across the federal public service, and established significant IT contracts for Aboriginal businesses. Lisa is an internationally recognized expert in Indigenous Cultural Heritage and is called upon to provide an Indigenous lens to a wide variety of topics that include World Heritage and major architectural projects and was a member of the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board. She also attended the National Ballet School and is featured in a National Film Board production of Indigenous peoples in the arts. Rob was the Vice President of Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation at Parks Canada and was largely responsible for the Agency’s recognition as a leader in meaningful relationship building with Indigenous peoples. He continues to work to advance Conservation through Reconciliation in his role as board member to the Innu Cooperative Management Board for Mealy Mountains National Park Reserve as well as the Nature Conservancy of Canada.

Finding a home for unique collection

When it came time for James to move into a care home, his son Ron took the initiative to find the right home for the large collection of books. Although there was significant monetary value, it was deemed more important to have the collection continue to educate and perhaps find its way back to Nova Scotia. Serendipity steps in when Ron is informed by Lori and Siobhan from Dalhousie’s Office of Advancement that resources were just made available to build an Indigenous Community Center within the library. The University took on the two-year effort to wade through 33 boxes (almost ¾ of a ton) of books.

James believes that knowledge is the most important thing that can be passed on to future generations and that education allows one to rise like he did out of the ashes of the residential school.

As Ron states on behalf of his siblings, “we are so grateful for how the university and all of you have embraced this project. It is nothing short of remarkable. It's heartwarming, it honors my father, it honors all of us. Together we have found a perfect home for a collection that can inspire all students but particularly Indigenous students to understand our complicated history and to contribute in their own way to the well being of all Indigenous people in this country”.

Recent News

- Empowering youth and transforming communities: Celebrating International Women in Engineering Day

- Hydrogen Applications Research Lab Tour

- Unlocking the power of green hydrogen

- Deputy Prime Minister Freeland Champions Federal Research Investments at Dalhousie's Water Quality Lab

- Dalhousie FSAE electric vehicle electrifies at New Hampshire Motor Speedway

- Engineering alumni inducted into the Tigers Hall of Fame

- Alum honours engineering professor Corinne MacDonald's impact as a role model and mentor through gift

- Mike Davis is in the business of doing business differently