News

» Go to news mainRobotic Boat to Sail Across the Atlantic

Sailing their way into the Guinness Book of World Records could be a challenge, but it’s certainly the goal for an engineering group at Dal. The team has custom built an autonomous, robotic sailboat capable of piloting itself from the coast of Nova Scotia to Europe.

Piotr Kawalec and Graham Muirhead are hoping to launch the team’s 2-meter vessel this spring as part of the Microtransat Challenge: A difficult race that many universities have attempted to accomplish, but failed to finish.

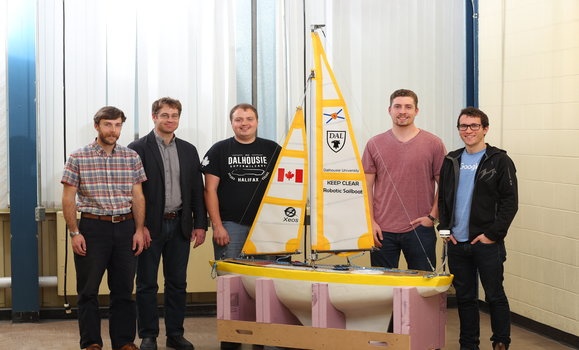

With help from a group of students and faculty from Dal’s departments of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, it’s taken approximately 5 months to build the sailboat. The team includes professors Rob Warner and J.F. Bousquet, students Andrew Dobbin, Thomas Gwynne-Timothy, Julia Sarty, and George Shannon, and other staff members.

The goal is to have the small sailboat leave the waters off the shores of the Halifax Harbour and travel across more than 3,500 kilometers of Atlantic Ocean to France.

As per the rules of the challenge, the vessel cannot exceed 4 meters in length and can use only wind power to make its sixty-day long journey.

Kawalec says that even though the Microtransat Challenge has been around for ten years, no one has ever designed an autonomous boat of this scale capable of sailing across the Atlantic Ocean.

“I think there are autonomous vessels out there that can sail across, but when you have a large boat to work with you can pack a lot more batteries and gear inside,” says Kawalec. “The challenge is that with something really small, the waves just toss it around. So far, no one has even got to the official start line.”

The start line is 200 kilometers off the shore of Newfoundland, with the finish line about 200 kilometers off the western shore of Europe along the French coast.

Disaster at sea

This isn't the first time Dal's Faculty of Engineering has competed in the Microtransat Challenge.

Their first attempt was in 2015 in partnership with Ensta Bretagne, a naval architecture school in France, The school supplied Dal’s team with the vessel that was used in the challenge. From there, the team equipped the vessel with appropriate controls necessary to make its sail across the ocean. Unfortunately, failure occurred about 500 kilometers into the boat’s journey.

“On our first attempt we lost it somewhere near Sable Island and never recovered it,” says Kawalec. “We had GPS tracking on the vessel and could see that it had started going around in circles. It just drifted around Sable Island for a couple of weeks and then we lost communication.”

Kawalec and Muirhead say the boat either sank or the batteries eventually died; A common occurrence for these types of small vessels that take part in the challenge.

“The Microtransat website hosts a tracking map of all the boats that are launched, so you can see that they all start off fairly well and then start to loop in circles,” says Muirhead. “Seems to be the normal pattern.”

This year, Muirhead and Kawalec are hoping to break tradition and set sail on a new path. The first step was building their sailboat from scratch.

Creating a new design

"I didn't work too much on the first boat, but it was provided to us by a naval architecture school. It was already made so we were constrained by what we had to work with,” says Kawalec. “When you’re building something like this, you want to line up your electrical systems with your mechanical systems. So, after the first year we decided that if we were going to do this again, we should build it the way we wanted.”

To start, the team spent a great amount of time considering all possible scenarios their boat could face on the Atlantic. This included how much battery power the boat required and what would happen if the vessel took on water.

“We can’t predict what we’re going to hit out there because it’s open ocean, but anything we could think of to implement that was feasible for us, we did, which was key for this boat,” says Kawalec.

The number one issue was the durability of the boat’s hull. The vessel used in the 2015 Microtransat Challenge had a hull that had been built of foam with a thin skin. The new sailboat however, is made out of Carbon Kevlar composite laminate.

“You can probably hit it with a hammer and it would be fine,” says Muirhead. “Making a strong boat was one of the biggest priorities”.

Muirhead says the other problem with the design of the 2015 vessel was that it had a fin keel; a long narrow plate that projects from the bottom of a vessel to give it greater lateral stability.

“The weight that keeps it upright was a long way down and it was catching quite a few weeds,” says Muirhead. “So we wanted to go with a full keel design that’s a little smoother along the water.”

The next step was trying to ensure that the boat was waterproof. To achieve that, the new hull has been built with a tightly secured lid that will prevent water from penetration. Though, Kawalec says if that should happen, all the electronic components inside the vessel have been individually waterproofed as well.

Should that fail, there is a plan B.

“Before we launch the vessel, we’re going to fill it with ping pong balls so if there was a breach and the vessel was to flood, it would still stay afloat,” says Kawalec. “The boat won’t perform as well because it’ll be heavier but it should still be capable of moving.”

Finally, communication with the boat itself was a key concern.

“The first boat had a GPS that could send its coordinates so we could track it, but we had no way of getting any other data out of it,” says Kawalec.

“And that was one of the biggest problems with the first boat,” adds Muirhead. “When the boat failed we didn’t really know why. We saw where it was, but that was all. To know more would have been very useful.

This year the team has implemented a satellite-based communication system that will provide them with data on the boat’s current condition.

“We’re hoping to do some monitoring as far as battery consumption, and we have sensors inside that can tell us if there is a hull breach or water taken on,” says Kawalec. “The vessel can also send back wind speed and other conditions. This way we can better understand what the boat is going through so that we can improve for next time.”

The sailboat also has a GPS tracking device that was provided to the team by Xeos Technologies, a local company in Halifax.

“They’re giving us two GPS trackers and they‘re maintaining them for us,” says Kawalec. “It’s a big help and something we wouldn’t be able to do on our own.”

Although weather conditions are the number one hazard for the attempt, there are other dangers to consider.

“Marine traffic is the second biggest danger for this boat,” says Kawalec. “High seas can toss it around but if it slams into a container ship, that could be a game changer for us.”

Another game changer; if someone picks up the boat on the open water.

“That’s partly why the boat says ‘Don’t touch’ and we have Piotr’s contact number on the back,” says Muirhead. “If you see this, just tell us where it is, please don’t take it home with you.”

They certainly did, but Kyle says it wasn’t easy.

Testing and launch

The team is still in the process of working out the final touches to their robotic sailboat, but hope to launch the vesset this April or May.

The team did have the opportunity to test their vessel last September, taking it out a few times in light and moderate wind conditions and watching as the sailboat bobbed up and down in the Halifax Harbor.

“There’s always this question of what conditions we should expect on the ocean and should there be changes in programming if there is a storm event,” says Muirhead. “We did enough testing in winds up to 20 knots, and the boat did pretty good in those waves.”

Muirhead says from now till spring, he’ll keep an eye on predicted weather conditions before deciding when to launch the boat. Although he and Kawalec are certainly hoping that their boat reaches the finish line, they admit that Europe is a long way from Halifax.

“We’re at the stage where we’re just trying to make gains on the previous attempt. That’s our big focus. How can we make this better than the last one?” says Muirhead

“The Dean did promise that if the sailboats makes it to Europe, we’re getting a trip to France to recover the boat,” adds Kawalec. “I think if it did make it across that would probably qualify for a Guinness World Record.”

Recent News

- Engineering alum takes stock of retail success

- Engineering alum delighted to come full circle with Oulton‑Stanish Centre

- Research Across Borders: Ryan O'Neil’s Unique PhD Experience in France

- Insight from American Indian Science & Engineering Society (AISES) and Indspire Conferences

- Honouring the Past and Shaping the Future: Women in Engineering Pay Tribute to the Victims of the Montreal Massacre

- Celebrating philanthropy with Dalhousie’s friends and supporters

- Dalhousie Professors Recognized with Prestigious CSME Medals

- USRA Grant Sparks New Paths in Renewable Energy for Dal Engineering Students