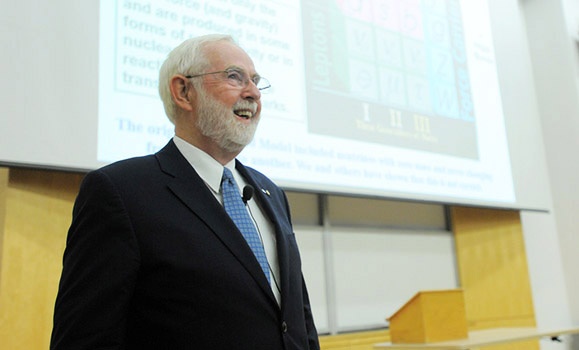

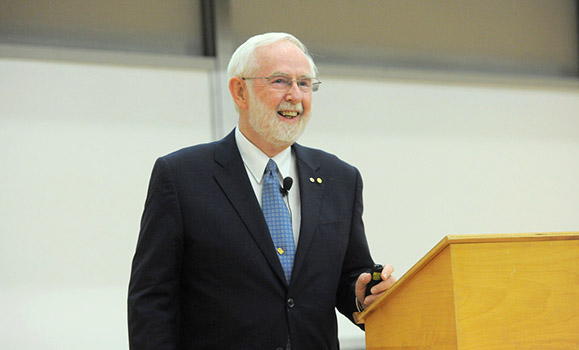

Thirty minutes into a lecture that filled two of Dalhousie’s largest classrooms to capacity, Arthur McDonald paused to acknowledge the complexity of what he was describing.

“It turns out that I haven’t been very successful, up to this point, in explaining [my research] and having it be understood by people,” he said. “I got some help from people here in Halifax.”

He then showed a clip from the Halifax-filmed TV show This Hour Has 22 Minutes, shot in October just after Dr. McDonald — a native of Cape Breton and a Dal alumnus twice over (BSc’64, MSc’65) — was announced as co-recipient of 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics. In the segment, Dr. McDonald attempts to explain his research on neutrinos, one of the universe’s fundamental particles, in simpler and simpler terms until, as a last resort, he describes them in terms of a classic Canadian delicacy.

“I must be the first person that ever won a Nobel Prize in Timbits,” he says in the clip, sorting through a familiar yellow box of chocolate, cherry-filled and old-fashioned glazed treats.

Such extreme simplification wasn’t necessary at Monday night’s lecture, which attracted physics aficionados and professionals of all stripes: from 12-year-old schoolkids eager to hear from a local science hero to faculty members who taught Dr. McDonald during his time at Dalhousie. But Dr. McDonald did his best to ensure everyone in the audience — which filled the McCain Building’s Ondaatje Hall and a livestream overflow room in the Scotiabank Auditorium — could relate to and understand the significance of his research.

“As a fellow physicist, it warms my heart to see so many people out here,” said Dal President Richard Florizone, who in his introduction recalled being a graduate student and first hearing about the research out of Dr. McDonald’s lab in Sudbury. “It was very exciting and very groundbreaking work.”

Shifting our understanding of the universe

Monday’s lecture was not Dr. McDonald’s first return to his alma mater: he received an honorary degree from Dalhousie in 1997 and also delivered the Department of Physics and Atmospheric Science’s E.W. Guptill Memorial Lecture in 2005. But Monday was first time back at Dalhousie as a Nobel Laureate.

Video: Watch Dr. McDonald's lecture at dal.ca/nobel

Dr. McDonald, professor emeritus at Queen’s University, was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics together with Takaaki Kajita (University of Tokyo) for research contributing to our understanding of neutrinos — tiny, subatomic particles generated in nuclear reactions within the sun that make their way to Earth, where they can pass through matter quite easily. Dr. McDonald explained that if you were to hold your thumb up to the sun, for example, there would be approximately 5 billion neutrinos going through your thumbnail in a single second.

“They’re outside people’s normal experience, but they’re very basic — along with electrons and quarks, they are the particles that we don’t know how to subdivide any further,” explained Dr. McDonald. “And they, together with the four forces, are what make up what is known as the standard model of elementary particles.”

This standard model presumed that neutrinos did not change their type, or “flavour,” in their journey from the sun to the earth because they didn’t have any mass. It was Dr. McDonald and his team that proved otherwise with their experiments at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, or “SNO.”

SNO inspired the title of Dr. McDonald’s lecture — How to tell a neutrino from a hole in the ground — because it was, literally, built in a hole in the ground. The laboratory is housed 2 kilometres underground at the Creighton Mine in Sudbury, built around a 1,000 tonne spherical detector filled with heavy water that can measure neutrinos travelling from the sun with great accuracy.

“We detect faint bursts of light, once an hour, from the sun, and we could eliminate all the other sources of radioactivity and make a clean measurement of neutrinos from the sun by doing that,” explained Dr. McDonald. “That enables us to understand, also, the way neutrinos affect the way the universe has evolved from the very early days, on the largest scales — the original big bang — to the most microscopic.”

And if that seems a bit too abstract, Dr. McDonald explained that understanding the physics of how neutrinos are generated within the sun is crucial to scientists working to figure out how to harness nuclear fusion to generate new sources of energy.

“It’s a prime example of how if you understand the laws of physics at a very detailed level, you can eventually apply that for the benefit of mankind,” he says. “That’s what’s happening as people use this information about how the sun burns to try to generate fusion power here on earth.”

A Dal-inspired legacy

In his lecture, Dr. McDonald detailed the history and evolution of his research and the SNO lab, from its early days as a project of 16 faculty members to a global collaboration that eventually counted 270 different researchers as paper co-authors. He showed photographs of visits from Stephen Hawking, shared images of mini-submarines used to swim through the detector’s heavy water, and discussed future research in the now-expanded SNOlab into everything from supernovas to dark matter.

He also talked about the experience of receiving his Nobel Prize in Sweden last December, which involved a week-long schedule with at least three major events each day. With about 15 of his collaborators also in attendance, he dined with Swedish royalty, delivered his Nobel lecture and (in typically Canadian fashion) was excited to meet Swedish former NHLer Mats Sundin, who played for Dr. McDonald’s favourite team, the Toronto Maple Leafs.

“It was the most unique week of my life, and certainly my wife Janet’s,” said Dr. McDonald. “We just had a wonderful time.”

Monday night’s lecture was also an opportunity for Dr. McDonald to reconnect with his Dalhousie roots. Earlier in the day while conducting media interviews, he caught up with his former student Ian Hill, now acting dean of the Faculty of Science. The Nobel Laureate also thumbed through a hard copy of his master’s thesis — which, with some work added to it after his time at Dal, is still one of the most highly cited papers of his career — before taking a peek at his old lab in the Sir James Dunn Building. As he walked through the halls, he asked passing students about their research interests.

“Here at Dal, I really got a great education. I enjoyed my undergraduate work very much, my excellent professors,” he said as he pointed to some of them in attendance, “and also had a great experience in my master’s degree, learning how to do experimental science for the first time.”

He strongly emphasized that the sort of groundbreaking science he conducted in his career can be done right here in Canada: “You’re limited only by your own energy and your own creativity,” he told students. And, in closing, he shared the motto of one of his mentors, Nobel Laureate and CalTech professor Willie Fowler: translated from Latin, “to the stars, with work and fun.”

“I’ve had a lot of fun in my career doing science,” said Dr. McDonald. “And it started with the attitude people have here at Dal: work hard, and enjoy what you’re doing.”

Video: Watch Dr. McDonald's lecture at dal.ca/nobel