With recent movements such as Idle No More and anti-fracking protests led by First Nations peoples in New Brunswick, the voices of indigenous people across Canada are being heard louder and clearer than ever before.

In the exhibition now on at the Dalhousie Art Gallery — “Beat Nation: Art, Hip Hop and Aboriginal Culture” – indigenous peoples’ voices are expressed in a range of media, from film to sound to sculpture. We asked Brian Noble, associate professor in Dal’s Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, to visit the exhibition and share his insights into indigenous cultures and indigenous-settler relations in Canada.

Assimilation and appropriation

For some time, researchers in disciplines such as sociology, anthropology and art history have been concerned with issues around appropriation of Aboriginal culture and cultural assimilation. Appropriation can occur when, for example, images and objects important to indigenous cultures are used out of context and without permission (such as a spiritually significant symbol “inspiring” the patterns on a multinational clothing retailer’s clothing line). Assimilation involves the absorption of one culture into another, usually dominant culture, with the assumption that something is lost in the process.

So what can be made of art that turns this around, and might seem both appropriation — with images and references taken from hip hop culture — and assimilation? Is something of Aboriginal culture “lost” as it merges with hip hop? Countering these notions, the curators of Beat Nation describe the works as “unique hybrids.” Dr. Noble takes it further: “The artists are using [hip hop references] to their advantage. They are practicing their freedom.”

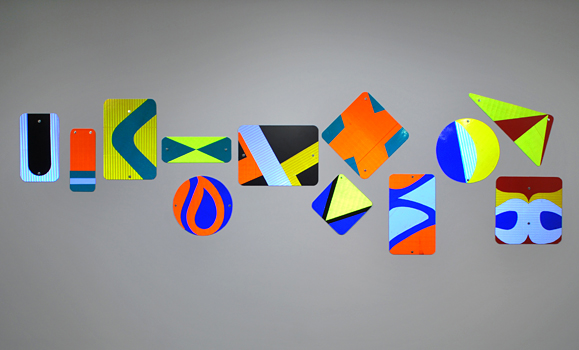

Rolande Souliere’s "Frequent Stopping Part II," 2008-2012. (Dalhousie Art Gallery photo)

Dr. Noble points to Rolande Souliere’s Frequent Stopping Part II — aluminum sheeting cut into various road-sign shapes and covered with configurations of blue, yellow, orange, green reflective tape — as an example. “The artist is drawing upon practices many first peoples would call traditional, but it’s a blurring of traditional and contemporary. [Yet,] this is not modern art!” he says. “They’re not modernizing, they’re indigenizing.”

The concept of “indigenization” comes from American anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, who helped revise “the predominant story within anthropology [regarding] the inevitability” of assimilation and modernization: “He said, it’s not that [indigenous people are] simply modernized, assimilated – [rather,] they are ‘indigenizing’ modernity. That’s what I see here: the road signs are being indigenized, made the artist’s own; they’re a kind of intervention” that “does culturally interruptive work, against the pressure of colonial imposition.”

Dr. Noble is also drawn to a mixed-media piece by Maria Hupfield. Jingle Boots (2011) consists of a pair of grey felt boots festooned with silver “jingles” — usually used to adorn dresses worn at a powwow dance or Mawio’mi ‚ along with a looped video of the artist jumping in the boots. “Adding these tin jingles to clothing was a way of taking something useful from the colonists,” says Dr. Noble. (Jingles, once made from deer hooves, were later made from the lids of chewing tobacco cans rolled into small cone shapes, pinched at one end and attached to fabric.)

He elaborates: “In archival images of Plains Cree or Blackfoot, you’ll see men … wearing the garb of the enemy, the rival, the colonizer, the settler: the cowboy hat, the buckled belt, the mounted police shirt.” This is known as “counting coup,” Dr. Noble adds. “If you take their shirt and wear it, you’re actually taking on some of the rival’s power. But you’re also inviting them to answer back, to join into a good relationship with you.”

Marie Hupfield's "Jingle Boots," 2011 (Dalhousie Art Gallery photo)

Jingle Boots has a third component: a duct-taped "X" on the floor that invites viewers to mirror the artist’s jumps. By doing so, viewers participate in the creation and movement of culture, literally and figuratively, and take the same physical position as the artist.

Dr. Noble also brings up anthropologist Alfred Gell, who believed “a [cultural] object is one expression in a whole network of histories and actions.” Gell referred to the “art nexus” (the social context that allows an artwork to promote agency), and Dr. Noble points out how Hupfield “pushes this nexus with her duct-tape dancing spot, inviting us to join the dance.” Dr. Noble adds that “art, at its most effective, is about concentrating so much of those multiple networks in something that it actually bursts with a kind of agency,” he says, holding one fist inside the other hand, then pushing it out as though from a shell.

“I see movement through history and through life,” he says. “Not just history in the usual sense, because these are all pieces of stories that are in motion, now, not in some lost past. Indigenous peoples are peoples in this moment, now, constantly engaging and reworking what they encounter, critical, yet inviting our participation.”

Connections and communication

Beat Nation is part of an “expanding set of interventions,” adds Dr. Noble. “When I look at the art, I have to look at Canadian history as colonial history, and then place this art as an intervention in that history.”

There’s also a connection between his thoughts on Beat Nation and the 2012 MacKay Lecture Series, for which he brought Michael Asch from the University of Victoria, and John Borrows from the University of Minnesota to speak on the topic of “Reconciliation: The Responsibility for Shared Futures.”

“[Dr. Borrows] talks about a respectful meeting between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples, about how we can communicate and co-generate new possibilities,” explains Dr. Noble.

“[Dr. Asch] speaks to the political question of how we can live here honourably with Indigenous peoples on their lands when they didn’t give them up,” he says, referring to 19th-century treaties of land sharing. The work in Beat Nation connects to both speakers’ ideas: “It’s saying to indigenous and non-indigenous peoples to start participating, start being critical and thinking about who we are, what our relations are,” says Dr. Noble.

He’ll do his part to spark such a dialogue this fall in a new first-year seminar course, Retelling Canada Through Indigenous Settler-Relations. He hopes to “engage students in the knowledge that I’ve been lucky to garner from many years of working with native peoples. I’ve thought about how students can begin to recognize that the history they learned in school might not be credible. What are the other stories that should be told?”

Beat Nation is at the Dalhousie Art Gallery (and the SMU Art Gallery, as well) until May 18.