Dalhousie’s newest Wave Glider is currently on her maiden mission — and it has a shark in her sights.

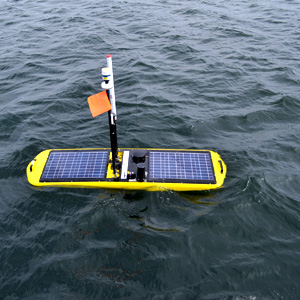

A key tool of the Dalhousie-hosted Ocean Tracking Network, Wave Gliders are unmanned marine vehicles built with the support of partner Liquid Robotics. They are deployed in the ocean where they can stay in the water for months, even years, due to their durability and use of solar and tidal energy.

“It has proven itself as an economical and robust platform with the power to operate for extended periods of time in conditions ranging from polar to tropical regions and reports via satellite at all times,” says Fred Whoriskey, execuctive director of the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN).

OTN’s newest Wave Glider, named the David Lilienfeld, was launched from Prince Edward Island on May 16. It's currently travelling from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Halifax, tracking animal movements and documenting oceanographic conditions. Its journey was highlighted during the opening ceremony of the Dalhousie Ocean Sciences Building, which will house OTN as well as offices and labs for other Dal-hosted oceans research projects.

Read also: Dalhousie Ocean Sciences Building opens its doors

The glider will also make its way to Sable Island and hopefully make contact with Lydia — a 2,000-pound great white shark OTN has been tracking along the eastern seaboard in collaboration with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Shark Research Program.

Lydia, being tagged and released by OCEARCH off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida. Learn more about Lydia. (OCEARCH photo)

It will be a fitting encounter, in no small part because of how the glider got its name. David Lilienfeld was a young champion bodyboarder who was killed by a shark attack off the coast of South Africa last year.

The glider took Lilienfeld’s name in his memory, and as a reminder of how in tracking species like great whites and monitoring the open ocean, innovative technologies like Wave Gliders are ultimately in the service of humans and a benefit to human life and livelihood. Wave Gliders can provide us with further insight on how we as humans can co-exist with the thousands of species that make up the vibrant ocean ecosystem.

Read also: Tracking sharks to prevent attacks (Dal News, August 2012)

Collecting large volumes of data

Wave Gliders have been a revolutionary tool for the Ocean Tracking Network, a $168-million research network hosted at Dalhousie that brings together experts from around the globe to track marine species and help us better understand the changing ocean. Gliders have the ability to collect an extensive amount of data relating to the migration of marine life, how climate change affects their behaviour and more, at impressive depths.

“There’s actually a lot of work that goes into the mission planning because we need to make sure that it’s safe,” explains Richard Davis, technical director for the OTN Glider Group. “The route of the Wave Glider is determined by a set of criteria that include safety of the personnel, the safety of our assets and our science objectives. These are all important considerations to make.”

“There’s actually a lot of work that goes into the mission planning because we need to make sure that it’s safe,” explains Richard Davis, technical director for the OTN Glider Group. “The route of the Wave Glider is determined by a set of criteria that include safety of the personnel, the safety of our assets and our science objectives. These are all important considerations to make.”

Equipped with the Airmar WeatherStation, Wave Gliders can monitor and help predict weather conditions, identifying events like hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes and other significant changes in weather patterns to help alert coastal communities, fishing vessels, oil rigs and other places where the sea can put them at risk.

Each time the Wave Glider comes back from a mission, there’s always something new being learned. On this particular journey, the David Lilienfeld will not only encounter sharks and fish that have been tagged, but grey seals on Sable Island that can actually register when other tagged species are nearby.

"They'll be collecting information on each other and sending it back our way in real time," says Sara Iverson, OTN's scientific director, of the cross-species collisions that the Wave Glider will be privy too. "It's a great example of the data we can collect thanks to international collaboration."

“This year, the Wave Glider will be travelling roughly 6,000 kilometres between the months of May to August,” says Davis. “That’s about double of what our glider travelled this time last year.” This suggests the David Lilienfeld may yet have many exciting discoveries left in her before returning to shore.