|

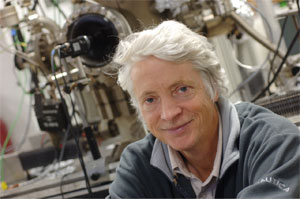

| Harm Rotermund worked closely with Nobel laureate Gerhard Ertl at Fritz-Haber Institute in Berlin. Together, they co-wrote more than 50 scientific papers. (Danny Abriel photo) |

Harm Rotermund was still in the shower early Wednesday morning when the phone started ringing off the hook – German news agencies wanting to speak to him about his mentor and colleague. His daughter took the cryptic message — “Ertl, Nobel, call back?”

“I see the note, ‘What’s this? Did he win the Nobel?’” recounts Dr. Rotermund, chair of Dalhousie’s Department of Physics and Atmospheric Science. “My daughter says, ‘I don’t know. Didn’t he already win that?’”

A dial-up connection is frustratingly slow when you’re looking to confirm such tantalizing details. Minutes felt like hours before Dr. Rotermund could charge up the New York Times online and see that, yes indeed, the Swedish Academy of Sciences had awarded physicist Gerhard Ertl the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“So, I called him right away,” says Dr. Rotermund, who has co-authored more than 50 papers with this year’s chemistry laureate, several of which are cited in the scientific background article to the prize. “I say, “Congratulations, for your birthday, and that other thing I’ve always wanted you to have.’

“And he says, ‘Oh thank you but I must go, the Chancellor (of Germany) can’t get through.’”

|

Dr. Rotermund describes his former boss as warm-hearted, adventurous and driven by a deep curiosity: “When we were doing research, we would come up to him and say, ‘I think I have a good idea. Can we try it?’ And he’d say, ‘If it works, great. If it doesn’t, you would have learned a lot anyway.’”

Dr. Ertl’s brilliance — “he is on an order of magnitude above the rest of us,” says Dr. Rotermund — lies in the area of surface chemistry, the chemical reactions that take place on surfaces and how this has laid the foundation for modern surface chemistry. Surface reactions are vital in many processes today, for example, in cleaning the exhaust from cars and in creating artificial fertilizers through the interaction of nitrogen and hydrogen. The study of surface reactions has also led to breakthroughs in other fields, including electronics and air conditioning.

Dr. Rotermund was enticed to come to Dalhousie a year ago, and one of the first things he did was to invite Dr. Ertl, who retired in 2004, to present the Guptill Memorial Lecture 2006, organized by the Department of Physics and Atmospheric Science.

“It was wonderful to show him around Dalhousie,” he says. “He’s my godfather in science.”

Dr. Rotermund’s own research continues at Dalhousie; his lab in the basement of the Dunn Building is set up with about $2-million worth of equipment he brought with him from Germany. Supported by an NSERC accelerator grant, his research involves the investigation of surface reactions in catalytic converters. Deadly carbon monoxide reacts with oxygen on a platinum surface in catalytic converters to create carbon dioxide. But even though very little platinum is used (just two to three grams), it is extremely costly. Dr. Rotermund is trying to find other surfaces that can do what platinum does without the expense.